Hurston was born in 1891 in Alabama, the daughter of a Baptist minister and school teacher. At the age of three, her family moved to Eatonville, Florida, the town where she would later return to conduct her anthropological field work. After her mother’s death in 1904, Hurston held a series of jobs as she struggled to continue her education. In 1918, when Hurston was 26 years old, she was finally able to graduate from high school in Baltimore. Eager to continue her education, she began studying at Howard University and later transferred to Barnard College, where she was the only African American student at the college. It was at Barnard that Hurston met Franz Boas, a pioneer of American anthropology who was a professor at Columbia University at the time. Boas became Hurston’s advisor and hired her to conduct ethnographic research in African American communities in New York City. After Hurston graduated with her B.A. in anthropology in 1928, she wanted to use her new skills to learn more about the cultural traditions of her childhood.

|

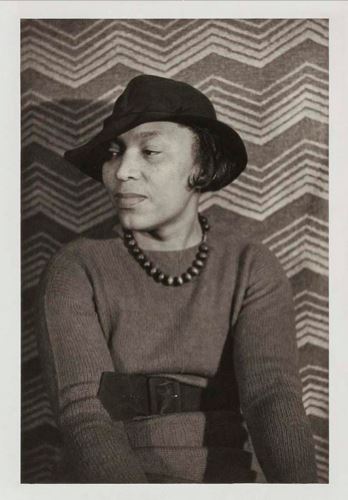

| Zora Neale Hurston, 1935. Smithsonian American Art Museum. |

"Florida is a place that draws people," Hurston later wrote about her field work in the South, including "white people from all the world, and Negroes from every Southern state surely and some from the North and West. So I knew that it was possible for me to get a cross section of the Negro South in one state." Beginning in her home town of Eatonville, Hurston visited front porches, saw mills, private homes, and bars to collect hundreds of folktales. Working in the same community that she grew up in, Hurston had a considerable advantage over other anthropologists. “Folklore is not as easy to collect as it sounds,” she admitted, “the best source is where there are the least outside influences and these people, being usually underprivileged, are the shyest.” In Eatonville, like many other small rural communities in the South, there was a general mistrust of outsiders, especially those from the North. “They are most reluctant at times,” Hurston added, “to reveal that which the soul lives by.” Fortunately, Hurston was no outsider and knew the best places to hear folktales in town- the same places she had been as a child.

|

| Franz Boas, undated. Photo Lot 33: Portraits of Anthropologists, circa 1860s-1970, National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History. |

As important as Hurston’s anthropological and literary work is, she was an obscure and misunderstood figure for most of her life. Though Mules and Men was critically acclaimed, it still faced criticism for Hurston’s decision to write in African-American dialect. Despite her publication of many other books and novels such as Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston’s writing career ended in the late 1940s. After a series of financial and health issues, Hurston died in 1960. It wouldn’t be until many decades later that her literary and anthropological accomplishments were finally recognized.

|

| NAA MS 7532: "Negro Tales From the Gulf States," 1927-1929. National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History |

The National Anthropological Archives and the Human Studies Film Archives are fortunate to have many materials that shed light on the cultural heritage of African American communities. The NAA is home to Zora Neale Hurston’s original manuscript of African American stories that was later published as Mules and Men in 1935. Simply called “Negro Tales From the Gulf States,” it contains Hurston’s documentation of African American folklore without any editing or changes that were made for publication, and it shows her hand-written edits and notes. The manuscript was published posthumously in 2002 as Every Tongue Got to Confess: Negro Folktales From the Gulf States.”

At the Human Studies Film Archive, there are a number of original film recordings of African American life and cultural practices in the twentieth-century South. The oldest of these films is “Ye Old Time Coon Hunt,” created by Field and Stream magazine in 1917. Originally intended to be a travelogue style “interest film” to be shown in movie theaters, it shows African Americans participating in a raccoon hunt and celebrating with a communal dance afterwards. The HFSA also has a 1930s film of a Shouter service shot by early documentarian Ralph Steiner. This service, common on the Georgia coast and Sea Island, features dances and other movements that were part of the Ring Shout tradition (an important spiritual and cultural tradition among African Americans). The film was studied by production staff for the 1998 movie Beloved to ensure historical accuracy in their portrayal of a Shouter service. Finally, the HFSA is home to film recordings of Georgia Sea Island Singers from the 1960s. These African Americans performed songs from the Gullah culture of Georgia and South Carolina, and were recorded by noted folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes. These film clips, like Hurston’s own research, reveal the everyday lives and culture of African Americans in the rural, twentieth-century South.

Tyler Stump

Processing Archivist

National Anthropological Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment