By Mikaela Hamilton and Nathan Sowry

On February 16th, 1945, nearly 20 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the first anti-discrimination law in the United States was signed into effect. The Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945 was created to address discrimination against Indigenous populations within the Alaskan territory by banning segregationist policies based on race. The successful passing of this act has often been credited to the dedicated work of Elizabeth Wanamaker Peratrovich (Tlingit), a prominent figure in the fight for equality and civil rights in the early twentieth century.

As of this month, the Peratrovich family papers are now available online, and will soon be available for research and reference in the National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center. This collection includes photographs, audio recordings, correspondence, and newspaper clippings documenting the life and important civil rights work of Elizabeth and her husband Roy.

|

| Elizabeth Wanamaker Peratrovich, 1911-1958. Peratrovich family papers (NMAI.AC.078), NMAI.AC.078_001_01_021. |

Elizabeth (Ḵaax̲gal.aat) was born on July 4, 1911, in Petersburg, Alaska, as a member of the Lukaax̱.ádi clan, in the Raven moiety of the Tlingit nation. Elizabeth spent the first decade of her life in Sitka, a coastal city in southeast Alaska, until her family moved further southeast to the Native village Klawock, where Elizabeth met her future husband, Roy Peratrovich (Tlingit). Although Elizabeth and Roy spent their early years at segregated boarding schools, they were able to graduate from Ketichikan High School, which was integrated following a lawsuit won by attorney William Paul (Tlingit). In 1931, Elizabeth married Roy Peratrovich. They had three children: Roy Jr., Loretta Marie, and Frank Allen.

In 1941, the Peratroviches moved to Juneau, the capital of the Alaska Territory, in search of more opportunities for themselves and their children. Although they encountered hostile white homeowners who refused to rent to Native Americans, they persevered to become one of the first Indigenous families to live in a non-Native neighborhood. They soon took on leadership roles within the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood. Throughout Juneau, discrimination was ubiquitous; local businesses commonly displayed signage reading "No Natives Allowed," "No Dogs, No Natives," and “We cater to white trade only." After encountering a “No Natives Allowed Sign” on a local inn just weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Elizabeth and Roy were driven to write a letter to Governor Ernest Gruening in protest, marking the beginnings of their political activism to establish legal protections for Indigenous people in Juneau and beyond. The letter read, in part:

“The proprietor of ‘Douglas Inn’ does not seem to realize that our Native boys are just as willing as the White boys to lay down their lives to protect the freedom that he enjoys. …We as Indians consider this an outrage because we are the real Natives of Alaska by reason of our ancestors who have guarded these shores and woods for years past."

|

| Letter from the Elizabeth and Roy Peratrovich to Ernest Gruening, Governor of Alaska, December 30, 1941. Peratrovich family papers (NMAI.AC.078), NMAI.AC.078_001_02_001. |

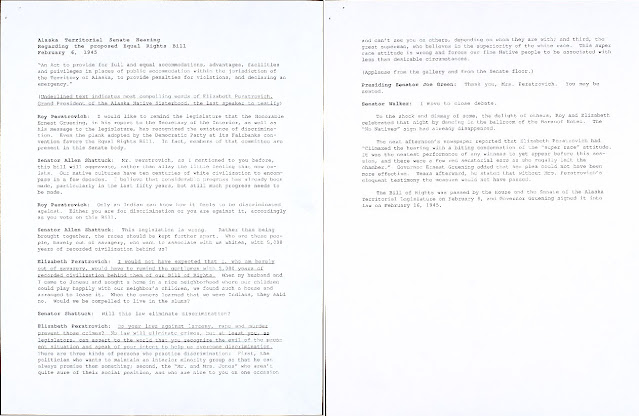

Successfully gaining Governor Gruening’s support, Elizabeth and Roy began a campaign to pass an anti-discrimination bill in 1943. With a vote of 8-8 in the House of Alaska’s two-branch Territorial Legislature, it failed to pass. Undeterred, Elizabeth continued to tirelessly campaign across the Alaskan territory. After garnering public support, Elizabeth and Roy, representing the Alaska Native Brotherhood/Sisterhood, brought a new anti-discrimination bill before the Alaska Senate in 1945. In an eloquent two-hour long testimony, Elizabeth stood before a white male majority and eloquently argued for an end to racial discrimination within Alaska.

During the hearing, Allen Shattuck, a Juneau territorial senator, asked Elizabeth “Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites, with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?” Elizabeth famously responded, “I would not have expected that I, who am ‘barely out of savagery,’ would have to remind gentlemen with five thousand years of recorded civilization behind them, of our Bill of Rights.” A local newspaper printed that she “shamed the opposition into a ‘defensive whisper.’” The Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945 was signed into law by Governor Gruening on February 16, 1945. The Act provided that all Alaskans be entitled to “full and equal enjoyment” of public areas and businesses and banned signs that discriminated based on race. This marked the end of “Jim Crow” laws within Alaska.

|

| Transcript of Alaska Territorial Senate Hearing regarding proposed Equal Rights Bill, February 6, 1945. Peratrovich family papers (NMAI.AC.078), NMAI.AC.078_001_02_082 and NMAI.AC.078_001_02_083. |

In recognition of her antiracist advocacy to provide equal accommodation privileges to all citizens regardless of race, in 1988 the state of Alaska posthumously established February 16th as Elizabeth Wanamaker Peratrovich Day. More recently, celebrating the 75th anniversary of Alaska’s Anti-Discrimination Law, Elizabeth Peratrovich appeared on the 2020 Native American $1 coin design. That same year, a Google doodle featuring the work of Tlingit and Haida artist Michaela Goade (Sheit.een) commemorated Elizabeth’s life and activism. Elizabeth and Roy’s efforts helped to pave the way for continued Indigenous activism within the United States.

Mikaela (Mik) Hamilton, Intern, National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center

Nathan Sowry, Reference Archivist, National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center