Showing posts with label Education. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Education. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

Connecting Black History through Transcription

In recognition of Black History Month, the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Anacostia Community Museum are collaborating to discover hidden connections across their respective collections. To start off the month NMAAHC and ACM highlight collections relating to African American education history.

After the Civil War, many of the first colleges for African Americans were established to provide training for teachers and future leaders. Now known as HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), these schools educated some of the most famous African Americans of the twentieth century including Booker T. Washington (Hampton University), W.E.B. Du Bois (Fisk University), Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Morehouse College), Ralph Abernathy (Alabama State University), Thurgood Marshall (Lincoln University), Katherine Johnson, (West Virginia State University), Marian Wright Edelman (Spelman College), and Oprah Winfrey (Tennessee State University).

One of the earliest HBCUs was Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia. Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) was founded in 1868 by General Samuel Chapman Armstrong with the support of the American Missionary Association. In its early days, Hampton trained African American educators. The school also emphasized self-improvement and job training to enable students to become gainfully employed and self-supporting as craftsmen and industrial workers. Listed in Hampton Classes 1871-1898 are the names of the graduates of Hampton Institute between 1871 and 1898. Included in this reference book are two of Hampton’s most famous alumni: Booker T. Washington (founder of Tuskegee Institute) and Robert Sengstacke Abbott (founder of the Chicago Defender). Help us transcribe this document and let us know if you find other famous alumni on these pages?

We invite the public to transcribe letters, catalogues, playbills, scrapbooks and programs on the Smithsonian Digital Volunteers: Transcription Center to help us become aware of people, places, and events buried within these documents.

Jennifer Morris, Anacostia Community Museum

Courtney Bellizzi, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Douglas Remley, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Labels:

African Americans,

Archives,

Black History Month,

Collections,

Education,

Transcription Center

Monday, March 21, 2016

One Stop Search Centers

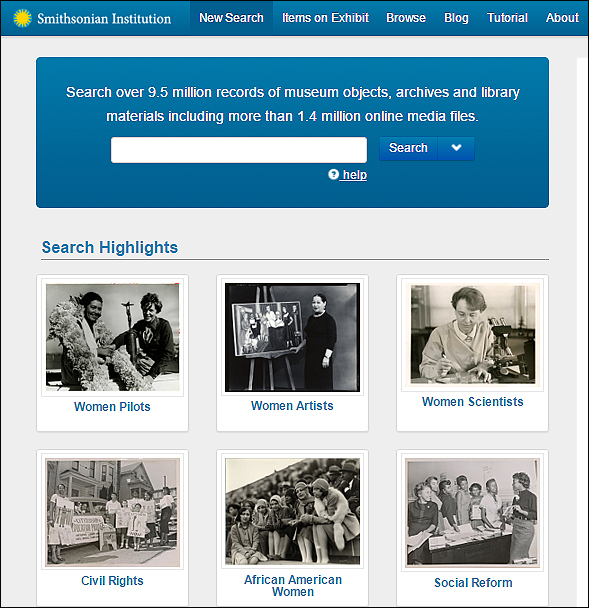

Modern museum management has moved into an interactive model emphasizing education and public engagement. In the past 15 years, collections management has been handled by using sophisticated Collection Information Systems (CIS) followed by quick publishing of most museum collections online for public searching and display.

Libraries, archives, and museums are considered complementary organizations that are making efforts to promote public education and engagement through their collections. Online catalogs and websites are expected to provide full and in-depth collection information that goes far beyond offering superficial eye-candy. These websites can now reach users around the world who may not be unable to visit the libraries, archives and museums physically.

Desire for a "One Stop" Search Online

The libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) at the Smithsonian used to maintain separate online catalogs within their respective professional fields. The Smithsonian has many museums, libraries, archives, a National Zoo, an Astrophysical Observatory, and several Science Research Centers. The Smithsonian’s subject areas cover arts and design, culture and history, science and engineering with 138 million collection objects. The Smithsonian has several hundred highly specialized database systems, websites, and catalogs. This should be a researcher’s information heaven, but trying to find the right information from the Smithsonian can be a challenge.

The solution was to create a “one-stop” search center that aims to include all online collections from the Smithsonian libraries, archives and museums. This Smithsonian's Collections Search Center (http://collections.si.edu) was launched in 2007 as one of the first large-scale single search center in the United States. It currently contains 9.5 million catalog records with 1.4 million images, sound files, and video recordings. These records describe books, journals, and trade catalogs from our libraries; photographs, manuscripts, letters, postcards, posters, sound- and video-recordings from our archives; and paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, decorative arts, ceramics, maps, portraits, scientific specimens, rockets, and airplanes from our museums.

The features of the Collections Search Center include keyword searching, filtering, various viewing options, slideshow, social media sharing, and a time-slider. The website is built to be mobile friendly.

The Collections Search Center only needs simple keywords to begin a search. The records returned in the search results are ordered according to the relevancy of the records to the search terms, with the best matched records listed at the top of the results list. Users can further enhance their search results by applying filters (faceted searching) by name, object types, subjects, time frame, geographical location, culture groups, scientific names, etc.

Once fully integrated into the Collections Search Center, the data from the Smithsonian's various databases works together in a harmonious fashion. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Desire for a "One Stop" Search Online

The libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) at the Smithsonian used to maintain separate online catalogs within their respective professional fields. The Smithsonian has many museums, libraries, archives, a National Zoo, an Astrophysical Observatory, and several Science Research Centers. The Smithsonian’s subject areas cover arts and design, culture and history, science and engineering with 138 million collection objects. The Smithsonian has several hundred highly specialized database systems, websites, and catalogs. This should be a researcher’s information heaven, but trying to find the right information from the Smithsonian can be a challenge.

The solution was to create a “one-stop” search center that aims to include all online collections from the Smithsonian libraries, archives and museums. This Smithsonian's Collections Search Center (http://collections.si.edu) was launched in 2007 as one of the first large-scale single search center in the United States. It currently contains 9.5 million catalog records with 1.4 million images, sound files, and video recordings. These records describe books, journals, and trade catalogs from our libraries; photographs, manuscripts, letters, postcards, posters, sound- and video-recordings from our archives; and paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, decorative arts, ceramics, maps, portraits, scientific specimens, rockets, and airplanes from our museums.

The features of the Collections Search Center include keyword searching, filtering, various viewing options, slideshow, social media sharing, and a time-slider. The website is built to be mobile friendly.

The Collections Search Center only needs simple keywords to begin a search. The records returned in the search results are ordered according to the relevancy of the records to the search terms, with the best matched records listed at the top of the results list. Users can further enhance their search results by applying filters (faceted searching) by name, object types, subjects, time frame, geographical location, culture groups, scientific names, etc.

Once fully integrated into the Collections Search Center, the data from the Smithsonian's various databases works together in a harmonious fashion. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Example 1: Search for Warren

Mackenzi’s pottery, we found many different material types in the search

result:

·

7 ceramic

objects from American Art Museum

·

13 books about

Warren Mackenzi and American potters from Library

·

3 interview

transcripts from Archives,

·

1 sound

recording of Oral History from Archives,

·

3 letters

written by Warren Mackenzi from Archives,

·

Two more

related collections from Archives,

|

Example

2: Search for Alexander

Calder as an artist, we found hundreds of objects from the following 10 Smithsonian

libraries, archives and museums:

|

|

·

National Postal

Museum (5)

·

Hirshhorn

Museum and Sculpture Garden (47)

·

Smithsonian

American Art Museum (30)

·

National

Portrait Gallery (10)

·

Cooper Hewitt,

Smithsonian Design Museum (8)

·

Photograph

Archives, Smithsonian American Art Museum (48)

·

Archives of American

Art (154)

·

Archives of

American Gardens (15)

·

Smithsonian

Institution Archives (9)

·

Smithsonian

Institution Libraries (164)

|

The Collections Search Center has been a great success! Diverse object types work well together because of several critical decisions we made during the project implementation process.

The Smithsonian chose to use a data-ingested model rather than a federated-searching model. This required creating special data extraction programs for every database at the beginning of the data aggregation process. All data sets had to pass through a required data standardization process. Even though this was a large amount of work up front for the system's designers, it provided reliable data quality and guaranteed search response time. This approach has turned out to be much better for the users.

We created a metadata model which served as the frame work for all the data processing. The metadata was based on national and international data standards that supports data types for bibliographic and archival materials, three dimensional objects and scientific specimens. We consulted several existing data standards used by libraries, archives and museums such as MARC, CDWLITE, MODS, Doblin Core, and VRA Core. In the end we narrowed down to fewer than 30 core data elements. This data model has proven to be lightweight, flexible, and scalable over the years.

The Smithsonian started this massive project with only limited databases in the early phase of the project. This allowed the project to focus on the data elements and data mapping without being overwhelmed. The project was eventually expanded to include collections data from more than 50 Smithsonian organizations and from 95 different databases and sources.

For anyone who considers similar projects, we can offer the following few lessons learned:

We created a metadata model which served as the frame work for all the data processing. The metadata was based on national and international data standards that supports data types for bibliographic and archival materials, three dimensional objects and scientific specimens. We consulted several existing data standards used by libraries, archives and museums such as MARC, CDWLITE, MODS, Doblin Core, and VRA Core. In the end we narrowed down to fewer than 30 core data elements. This data model has proven to be lightweight, flexible, and scalable over the years.

The Smithsonian started this massive project with only limited databases in the early phase of the project. This allowed the project to focus on the data elements and data mapping without being overwhelmed. The project was eventually expanded to include collections data from more than 50 Smithsonian organizations and from 95 different databases and sources.

For anyone who considers similar projects, we can offer the following few lessons learned:

- Start small and work with willing partners to build and demonstrate initial success.

- It is key to encourage participation from everyone within the organization, and to be respectful to their specific concerns while seeking solutions. It is also important to focus on collaboration over competition.

- Use national data standards to address data quality issues and minimize differences among data formats. Adherence to standards can help to defuse disagreements among staff from the different departments.

Looking Beyond the Smithsonian

In addition to the Smithsonian Institution’s successful project, there are other successful efforts to create single search systems around the world.

In addition to the Smithsonian Institution’s successful project, there are other successful efforts to create single search systems around the world.

In Europe, a coordinated effort created a “one stop search” portal called Europeana (http://www.europeana.eu/portal/). 37 countries joined in to contribute 39 million collection records from their libraries, archives, museums and cultural institutions. This internet portal serves millions of books, paintings, films, museum objects and archival records that have been digitized throughout Europe. In addition to searchable catalog records, multimedia files such as 23.3 million images, 507,000 sound files, 408,000 video files, 17,800 3D images and 15.2 million full text documents are available to the public. The Europeana portal attracts online visitors from more than 100 countries.

Trove, created by the National Library of Australia, is another great example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal for Australia. Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/ ) is a central online indexing system that includes more than 426 million books, images, historic newspapers, maps, music, archives records from 1500 contributing libraries, archives, museums, and cultural institutions. The National Library of Australia combined eight different online databases into a new single discovery interface. Trove's collection highlights include 136 million journals and research articles, 608,000 maps, 567,000 diaries, letters and archives records, 3.6 million music, sound and videos, 8 million photographs of objects, and 168 million digitized newspapers. Given such a large collection of rich information, Trove provides an easy way to filter a search by material types such as books, photographs, music and video files, maps, diaries and archives, websites, people and organizations.

One final example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal is the Digital Public Library of America in the United States. The discovery portal DPLA (http://dp.la/) is a union catalog for public domain and openly licensed content held by the nation's archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This is a fairly new system which was first launched in 2013, and it is still growing very fast. Records are contributed to DPLA following a model organized around "Content Hubs" and "Service Hubs". DPLA content hubs are large libraries, museums, archives, or other digital repositories that directly contribute large quantities of content to DPLA. DPLA service hubs are state, regional, or other collaborations that host, aggregate, or otherwise bring together digital objects from libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This model enables DPLA to collect a large number of quality records quickly. In just two years’ time, DPLA has already provided 10 million items from repositories across the United States. Organizations which have led the effort include Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and Records Administration, New York Public Library, California Digital Library, the J. Paul Getty Trust and others.

One final example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal is the Digital Public Library of America in the United States. The discovery portal DPLA (http://dp.la/) is a union catalog for public domain and openly licensed content held by the nation's archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This is a fairly new system which was first launched in 2013, and it is still growing very fast. Records are contributed to DPLA following a model organized around "Content Hubs" and "Service Hubs". DPLA content hubs are large libraries, museums, archives, or other digital repositories that directly contribute large quantities of content to DPLA. DPLA service hubs are state, regional, or other collaborations that host, aggregate, or otherwise bring together digital objects from libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This model enables DPLA to collect a large number of quality records quickly. In just two years’ time, DPLA has already provided 10 million items from repositories across the United States. Organizations which have led the effort include Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and Records Administration, New York Public Library, California Digital Library, the J. Paul Getty Trust and others.Conclusion

One Stop search centers are important information search portals that build bridges among cultural institutions for all object types and materials. Their purpose is to serve the public and researchers to find the right information more easily through one-stop searching. Such search centers will only work if they are based on commonly shared data standards and controlled vocabularies. Hundreds of millions of catalog records have been created with quality data conforming to minimum standards, and these records have built up over a long period of time. A search center must be rich and deep in its contents, including images, sound and video files and full text documents, to attract and retain users. The success of the Smithsonian Collections Search Center should be measured by the usage rate of our featured objects and materials, and by the number of people who have consulted it online.

Creating a great single search center is complicated and takes a huge effort to succeed, but in the end, it is well worth the effort to create a collections discovery platform that the public will enjoy using.

Ching-hsien Wang, Project Manager for Smithsonian Collections Search Center

Collections Systems & Digital Assets Division, Office of the Chief Information Officer

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Langston Hughes: For livin' he was born

|

| Postcard from Langston Hughes to Moses Asch, undated. |

The funny thing about legendary figures is that it can be easy to forget that they are still just people.

We tell stories about these individuals and reference quotes about the great things they said, until the fact that they walked the earth, had friends, and schedules to keep seems to be lost. It's not anyone's fault; legends are just so incredibly good at staying relevant that we have no choice but to name places after them and write blog posts (belatedly) honoring their birthdays, so we can continue to remember them long after they stopped walking the earth.

|

| Letter from Langston Hughes to Marian Distler, mentioning Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune, circa 1955 [?] |

This is the way I think about Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902-May 22, 1967) when I go through his correspondence and related ephemera tucked in a collection filled with the breadcrumbs of so many inspiring people. The things legends leave behind help us understand what it was that made them so iconic, but they also show that they had their share of dreams and disappointments.

Langston Hughes recorded, produced, and/or participated in many albums for Folkways Records, and the Moses and Frances Asch Collection contains many years of letters, production notes, and promotional materials detailing his fruitful work with Moses Asch, the record company's director. It is clear from his letters that he and Asch had a great deal of respect for each other, but they also show that they were friends. Hughes' letters often mention his extremely busy schedule ("I'm nothing but a literary sharecropper," he jokes in a letter from March 2, 1953) and his looking forward to carving out some personal time ("Only one more out of town date this season, gracias a dios, in Massachusetts this weekend. Then I'm through traveling and can stay home and create," from a letter dated April 25, 1953). And then there's this mischievous line from a January 14, 1955 letter, "(And remind me to tell you, when I see you, why [George Washington] Carver had such a high voice)."

It is absolutely clear from these materials that he was a brilliant, endlessly talented man. I love the note he writes to Asch on the sheet music to a song he composed:

|

| Note from Langston Hughes to Moses Asch, on sheet music for "Freedom Land," 1963-1964. |

Not surprisingly, Hughes had a very clear understanding of Moe's vision for Folkways:

In November, a novel of mine called, TAMBOURINES TO GLORY, with a background of Harlem gospel churches is being published by John Day. The same month, THE BOOK OF NEGRO FOLKLORE, which I co-edited with Arna Bontemps will be published by Dodd Mead. Both of these books contain a number of gospel lyrics. Gospel songs, in my opinion, are the last wellspring of Negro folklore as expressed in words and music. So far as I know, Folkways has not recorded any gospel songs. Since this is a contemporary folk expression and a field in which I have been working intensively for the past few years, I am wondering if you would be interested in doing a long playing record with a gospel folk group...of my own gospel songs* which I have written with a talented Harlem gospel musician, Jobe Huntley.

This letter was written on September 22, 1958. The album Tambourines to Glory was recorded on October 3, 1958--an extremely rare turnaround for the consistently short-staffed Folkways Records.*I heard Mahalia Jackson rehearse two of these songs of mine she likes and says she will eventually record. They really jump!

All of these words help me paint a better mental picture of the man behind "The Negro Speaks of Rivers." Langston Hughes--one of the first Great Poets I learned about as a child, was a real person before he was an icon, and he didn't operate in a vacuum. From the recording below, it is clear that Hughes went beyond poetry to confront the critical issues of his time (issues that, frankly, we still face today). In this excerpt from a recently digitized interview in the Asch Collection, two unidentified educators (or education specialists) speak with Hughes in his home about how to encourage creativity in schools.

The wonderful thing about archival materials is that they make it possible for us to explore history in ways books (or blog posts) couldn't possibly replicate. In these materials, Langston Hughes comes alive and shows us what it means to be born for living.

-Cecilia Peterson, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

Labels:

African American,

Artists,

Correspondence,

Digitization,

Education,

Folklife,

History and Culture,

Music,

Sound Recordings

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Treasures From American Film Archives: Beautiful Japan

Blogs across the Smithsonian will give an inside look at the Institution’s archival collections and practices during a month long blogathon in celebration of October’s American Archives Month. See additional posts from our other participating blogs, as well as related events and resources, on the Smithsonian’s Archives Month website.

In this new world of internet accessbility and, even before then, DVDs, how does an archives know how their collections are being used? We don't.

By chance, of course, an archivist may meet a professor who cheerfully announces that she uses a clip of one of the archives' films in a class. Such a chance meeting happened at this year's Northeast Historic Film Summer Film Symposium in Bucksport, Maine, when I met a professor of Japanese at the University of Rochester who screens a film clip from Beautiful Japan (1917-18) that is included in the National Film Peservation Foundation's first "Treasures From American Film Archives", DVD (first published in 2000). In an email Dr. Joanne Bernardi describes her use of the film clip:

"I use the excerpt in a class called "Tourist Japan," which explores Japan as destination in twentieth century visual and material culture. In addition to weekly screenings, I show short excerpts in class, and Beautiful Japan is one of them. Students then write a response to them on the course website. Other films that I show in the class are a NARA [National Archives and Records Administration] "The Big Picture" DVD ("You in Japan," 1957), a Japan Tourist Bureau film from the 1980s called "Destination Japan," and the 1932 Technicolor Fitzgerald travel film that is on the "China Seas" DVD, called "Japan in Cherry Blossom Time" (I think there are many films with this same title--a very popular subject!). Of everything I show, though, "Beautiful Japan" is the earliest footage, and the students are always bowled over by it. The excerpt is a good choice, showing footage of the Ainu bear ritual in Hokkaido and ending with a scene of foreign tourists dancing with Japanese women in kimono. I knew about the film for some time, but had not had a chance to see any of it myself until the Treasures DVD came out."

Benten Festival celebrated on Shiraishi Island. Benten (Benzaiten) is the Goddess of the Sea and one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan. (This is not the same clip that is included in the "Treasures" DVD.) Beautiful Japan was filmed by Benjamin Brodsky, an early travel-lecturer, who made the film under the auspices of the Imperial Japanese Railways.

With forty plus film clips on YouTube we can tell how many people are viewing and for how long and we can see the geographic distribution and if the clip is linked, embedded or shared but, still, we do not know HOW people are using HSFA's film clips. Is not how more important than how many?

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Back to School with Sicangu Lakota

|

| Sicangu Lakota (Rosebud Sioux) with Septima Koehler c.1900 |

For many people, the month of September means heading back to school, hitting the books, and getting ready to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic. At the National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, I stumbled upon a collection of Sicangu Lakota (Rosebud Sioux) children’s schoolwork dated 1899-1901. Further investigation revealed that the assignments were completed at St. Elizabeth Mission School in South Dakota under the tutelage of sisters Septima and Aurora Koehler.

This turn of the century schoolwork is remarkable for both its familiarity and elegance. The images pictured below are from children Eliza Standing Bear, Samuel Little Elk, and Annie Red Horse; primer class, first reader grade, and second reader grade, respectively. The first thing that caught my eye was the beautiful, sharp penmanship coming from such young children. On closer examination, the Sicangu Lakota children were learning the same poems, stories, and simple addition in 1901 that schoolchildren learn today, over one hundred years later.

Reading:

|

| Annie Red Horse tells the story of King Midas and his golden touch. |

Writing:

|

| Samuel Little Elk's illustration and penning of "Rock-a-bye Baby". |

Arithmetic:

|

| Eliza Standing Bear's illustrated arithmetic. |

Of the hundreds of thousands pages contained in the manuscript collection Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation records this small collection (only two folders!) of children’s school work are some of my favorite to read. It amazes me how I can connect to these materials a hundred years after they were created: looking at them, I can remember what it was like to be a child learning about King Midas, struggling with addition, and reciting "rock-a-bye baby".

Nichole Procopenko, Archives Scanning Technician, NMAI Archives Center.

Labels:

American Indian,

Archives,

Education,

Photographs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)