September is National Potato Month. Almost all the potatoes grown in

the United States are planted in the spring and gathered in the fall. It

is the time of year that schools in northern Maine have “harvest break”

when students work to dig and sort the season’s spud crop soon after

summer vacation.

Maine’s custom is one small part of the very long

and interwoven agricultural, economic, social, culinary, medical, and

ritual histories of this humble staple. It is a story that stretches

from ancient gardens in the Andean Mountains 10,000 to 8,000 years ago …

to perhaps Mars in the future? In the recent movie,

The Martian,

the stranded astronaut-botanist (played by Matt Damon), bases his

long-term survival strategy on the Red Planet, not completely

unfeasibly, on planting potatoes. But is the potato relevant for us

today?

A carbohydrate, the tubers have nutritional detractors who

point out that Americans consume far too many calories from white

starches, including processed potato products in the forms of French

fries and chips (along with the harmful fats and salt that go with

them). With dehydrated and other potato products, these foods account

for fifty percent of the potato market. Meanwhile, the annual

consumption of fresh potatoes in the United States has fallen from

eighty-one pounds per person in 1960 to forty-two pounds recently (the

official Government report

here).

Potatoes are a hot political issue: Congress has fought successfully to

keep the white potato in food assistance programs, including those of

school lunches and breakfasts, against recommendations from the

Department of Agriculture.

Following rice, wheat, and corn,

potatoes are among the most consumed food crop in the world. The tuber

is easy to grow in a variety of climates and soils, and is not as

thirsty for water as many other vegetables, producing a high yield from a

small area. Able to be stored for long periods, the potato is a good

source of vitamin C (surprisingly), potassium, phosphorus, magnesium,

vitamin B₆, and some iron. Inexpensive, lacking only calcium and

vitamins A and D, it is almost a complete food. Beginning with the

ancient civilizations of Huari and Tiahuanacu located in parts of

modern-day Peru and Bolivia, the spud has been insurance against famine,

providing sustenance when other crops failed.

If there is a food stuff that deserves a commemorative month or day (May 30

th in Peru), it is the potato.

|

| A selection of organic potatoes from both coasts: Idaho and Yukon Gold

from California; Honey Gold Nibbles, Gold Marbled Fingerlings, Purple

Peruvian, and Adirondack Red potatoes from the Mid-Atlantic area. There

are over a hundred varieties available. The petite type are growing in

popularity (quick to cook, creamy in texture) as a substitute for pasta

(photo by the author) |

Not surprisingly, the Smithsonian does not treat

the subject

as small potatoes. In most, if not all, of the twenty-one separate

libraries in the Institution, information on some aspect on the history

and culture of the potato can be found. So what better way to celebrate

the potato (

Solanum tuberosum) and find its relevancy than by

digging into some of Smithsonian Libraries’ holdings that tell its rich

story? From the Anthropology, American Indian, Natural History,

Horticulture and Botany libraries, the trade literature and cookery

collections of American History, and, of course, Special Collections,

all have original and secondary sources for an (almost) complete picture

of this highly significant plant.

Archaeological research finds

that the potato was first domesticated from wild plants on the shores of

Lake Titicaca in the Andes. With sophisticated agricultural technology,

including raised field terraces and irrigation systems, Pre-Inca

cultures came to thrive on huge yields of the crop. The Inca Empire

relied on potato storehouses, including a freeze-dried product (

chuña)

that could hold for years, in times of crop failures. Pedro de Cieza de

León, explorer and historian, described the cultivation and cooking in

his

Chronicles of Peru,

in 1540. Spanish conquistadors, who largely destroyed the Inca

civilization, brought the potato across the Atlantic. Early accounts are

a bit murky with the confusion between white (

papas) and sweet potatoes (

batata), but they were cultivated on the Canary Islands from 1565 and then onto the mainland of Spain.

|

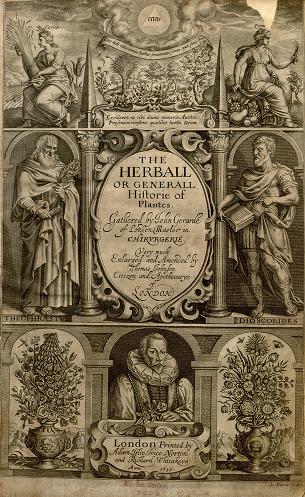

- John Gerard, The Herball, or, Generall historie of plantes

(Imprinted at London by John Norton, 1597). There had been an earlier

written description (but with no illustration) of the plant in Gaspard

Bauhin’s Phytopinax of 1596. The Dibner Library of the

Smithsonian Libraries has this first edition of Gerard. The Biodiversity Heritage

Library has digitized the copy in the Peter H. Raven Library, Missouri

Botanical Garden (pictured here).

|

Potatoes were being grown in London not long afterwards. The first

printed pictures of the potato plant appear in woodcut illustrations in

John Gerard’s great

Herball

of 1597. Gerard, who grew the plants in his own garden, misidentifies

the origin of the potato as Virginia. It was not introduced into North

America until the 1620s when the British governor of the Bahamas sent

the tuber, along with other vegetables, to the Jamestown colony

in Virginia. However, Derry, New Hampshire claims the first potato patch

in North America,

planted in 1719 when Scot-Irish immigrants settled in the area.

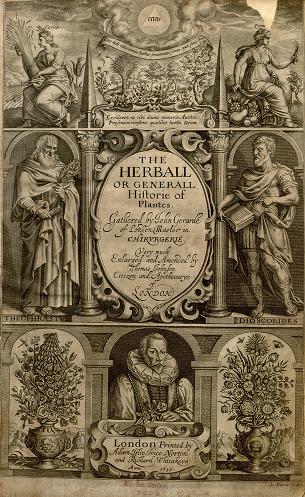

|

| The 1636 edition of Gerard's Herball. The author holds a spray

of potato flowers in the illustrated title page of the book, seen in the

bottom center, just above the imprint. The Cullman Library of the

Smithsonian has two copies; this image is from the scanned copy in the Peter H. Raven Library of the Missouri Botanical Garden (from the catalog of the Biodiversity Heritage Library). |

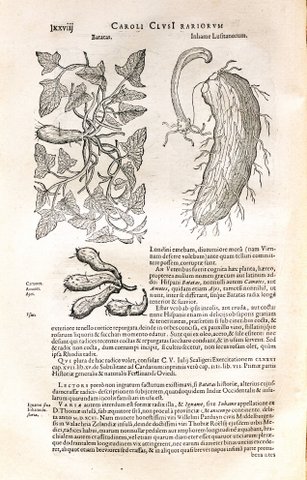

From England, the potato moved to France and then on to the Netherlands.

Carolus Clusius (or Charles de l’Ecluse) introduced the potato to the

Low Countries. Woodcut illustrations are in his

Rariorum plantarum historia (

The history of rare plants;

Antwerp, 1601). Because potatoes were a good source for preventing

scurvy on long voyages, they were distributed via shipboard provisions

to the far reaches of the world in the age of exploration. Potatoes also

lessened the effects of tuberculosis, measles and dysentery. But the

tuber became stigmatized as it moved from the exclusive botanical

gardens of the wealthy in the 17

th century, when it was thought to be poisonous and fit only for livestock or the truly indigent.

|

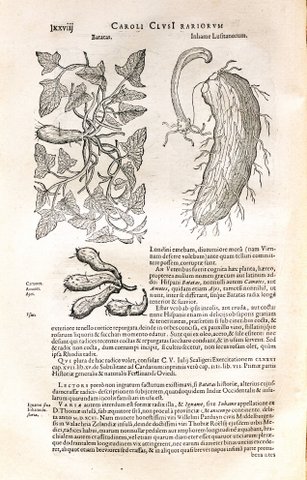

| Clusius' Rariorum plantarum historia (Antwerp, 1601). Images of

the white and the sweet potatoes (above and below) from the scanned

copy in the Peter H. Raven Library of the Missouri Botanical Garden by

the Biodiversity Heritage Library (link). The Smithsonian's Cullman Library also has the title. |

|

| Clusius also created the first European representation of the potato, a

lovely watercolor of 1588 of a plant in his garden. The work of art,

with a note written by Clusius, is now in the Plantin-Moretus Museum in

Antwerp (link here). |

In Europe and Russia during the second half of the 18

th

century the potato was vigorously promoted to lessen the economic

distress of successive disastrous harvests of corn and wheat. Various

groups and individuals produced pamphlets and books to educate and extol

the crop’s virtues, such as the

Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, and military pharmacist and agronomist

Antoine Augustin Parmentier. An example is

Memoria sopra I pomi di terra (

Memoire on the potatoes) of 1767, an Italian translation of a French publication (Dibner Library) that discusses varieties and cooking methods.

In

France, the tuber was particularly regarded as a poor person’s food.

Sadly, the Smithsonian Libraries does not own a copy of the important

Parmentier work,

Examen chimique de la pomme de terre (

Chemical examination of the potato,

1778). He was so successful in his efforts that some still believe he

invented the potato, and there are many dishes named for him, such as

the casserole of veal chops à la Parmentier.

By the 19

th

century, the potato was common and so prevalent that historians debate

its exact role in fueling the population explosion of the period. The

food stuff also was being put to other uses, such as in alcoholic

spirits. John Ham’s

The theory and practice of brewing, from malted corn and from potatos

(London, 1829), is one such treatise. There are many gardening manuals

in the Smithsonian Libraries that discuss all the types then being

developed and best methods of growing and storage. William Cobbett’s

The American gardener (London, 1821) has this charming entry:

"Potatoe – Every body knows how to cultivate this plant; and, as to its preservation during winter, if you can ascertain the degree of warmth necessary to keep a baby

from perishing, you know precisely the precautions required to preserve

a potatoe. – As to sorts they are as numerous as the stones of a

pavement in a large city."

But such dependency on a single crop, relied on by a huge population,

proved ripe for disaster. This came in the form of late blight disease

in the 1840s, which struck hard in Europe and was particularly

devastating in

Ireland. These catastrophes led to the development of disease-resistant plants, in particular by American horticulturist

Luther Burbank

who worked to improve the Irish potato; he bred a type in 1872 that

established the Idaho potato. These new varieties led to even more

potato dominance in food production and plantings around the world. It

is a story likely to play out again with climate change, as scientists

work to develop cultivars even more resistant to heat, drought and

disease. To lessen pollution and water use and help feed its exploding

population, China is now by far the largest producer of the staple in

the world. Will the potato once again save some parts the world?

(see Zuckerman, Larry.

The potato: how the humble spud rescued the western world. Boston, 1998 and this Wikipedia

entry on the subject).

|

| "Good seeds at fair prices": National Museum of American History Trade Catalogs of 1902 from Minneapolis, Minnesota (image from Wikimedia Commons of the copy in the National Agricultural Library) |

The extensive agricultural

trade literature collections in the Smithsonian illustrate the trends in the potato’s popularity and dominance into the 20

th century (one example linked

here). The evolution of the vegetable as source of sustenance to a snack food is also traced in the Libraries’ culinary

holdings. Thomas Jefferson had "potatoes served in the French manner" at a White House dinner in 1802 (not, strictly speaking, and

contrary to the myth,

the French fry). A relative of Jefferson’s, Mary Randolph, had seven

recipes for potatoes, including one “to fry sliced potatoes” in her

book,

The Virginia house-wife, or, Methodical cook.

The Dibner Library holds the fourth edition of this important cookbook,

published in 1830. The Russet Burbank potato, developed in the 1920s,

long, regular with a high sugar content, is the hybrid ideal for French

fries. Speaking of which, France and Belgium are still arguing over who

invented “French fries.”

|

| An artist book in the collections: French fries : a new play, written by Dennis Bernstein, Warren Lehrer ; designed by Warren Lehrer, 1984. |

This short history, centered on the Smithsonian Libraries collections,

merely skims the surface of the potato. So even if you tend to avoid

white potatoes in your diet, pick up one of the many, many accounts of

the spud to read or raise a fork to the potato this month and celebrate

this small vegetable’s big history in the world. In the words of

Winnie-the-Pooh creator A. A. Milne: “What I say is that, if a fellow

really likes potatoes, he must be a pretty decent sort of fellow”

(“Lunch” in

Not that it matters, 1919).

Julia Blakely

Special Collections Cataloger

Smithsonian Libraries

For further reading:

Chilies to chocolate: food the Americas gave the world. Tucson, 1992.

Hawkes, J. G.

The potatoes of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay: a biosystematics study. Oxford, 1969.

Ochoa, Carlos M.

Las papas de Sudamérica. Lima, Perú, 1999.

Salaman, Redcliffe N.

The history and social influence of the potato. Cambridge, 1985.

|

| Well, if you are going to have bacon with your potatoes, might as well

have sour cream as well. Photo by the author but the great recipe and story from the New York Times. |