Maine’s custom is one small part of the very long and interwoven agricultural, economic, social, culinary, medical, and ritual histories of this humble staple. It is a story that stretches from ancient gardens in the Andean Mountains 10,000 to 8,000 years ago … to perhaps Mars in the future? In the recent movie, The Martian, the stranded astronaut-botanist (played by Matt Damon), bases his long-term survival strategy on the Red Planet, not completely unfeasibly, on planting potatoes. But is the potato relevant for us today?

A carbohydrate, the tubers have nutritional detractors who point out that Americans consume far too many calories from white starches, including processed potato products in the forms of French fries and chips (along with the harmful fats and salt that go with them). With dehydrated and other potato products, these foods account for fifty percent of the potato market. Meanwhile, the annual consumption of fresh potatoes in the United States has fallen from eighty-one pounds per person in 1960 to forty-two pounds recently (the official Government report here). Potatoes are a hot political issue: Congress has fought successfully to keep the white potato in food assistance programs, including those of school lunches and breakfasts, against recommendations from the Department of Agriculture.

Following rice, wheat, and corn, potatoes are among the most consumed food crop in the world. The tuber is easy to grow in a variety of climates and soils, and is not as thirsty for water as many other vegetables, producing a high yield from a small area. Able to be stored for long periods, the potato is a good source of vitamin C (surprisingly), potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin B₆, and some iron. Inexpensive, lacking only calcium and vitamins A and D, it is almost a complete food. Beginning with the ancient civilizations of Huari and Tiahuanacu located in parts of modern-day Peru and Bolivia, the spud has been insurance against famine, providing sustenance when other crops failed.

If there is a food stuff that deserves a commemorative month or day (May 30th in Peru), it is the potato.

the subject as small potatoes. In most, if not all, of the twenty-one separate libraries in the Institution, information on some aspect on the history and culture of the potato can be found. So what better way to celebrate the potato (Solanum tuberosum) and find its relevancy than by digging into some of Smithsonian Libraries’ holdings that tell its rich story? From the Anthropology, American Indian, Natural History, Horticulture and Botany libraries, the trade literature and cookery collections of American History, and, of course, Special Collections, all have original and secondary sources for an (almost) complete picture of this highly significant plant.

Archaeological research finds that the potato was first domesticated from wild plants on the shores of Lake Titicaca in the Andes. With sophisticated agricultural technology, including raised field terraces and irrigation systems, Pre-Inca cultures came to thrive on huge yields of the crop. The Inca Empire relied on potato storehouses, including a freeze-dried product (chuña) that could hold for years, in times of crop failures. Pedro de Cieza de León, explorer and historian, described the cultivation and cooking in his Chronicles of Peru, in 1540. Spanish conquistadors, who largely destroyed the Inca civilization, brought the potato across the Atlantic. Early accounts are a bit murky with the confusion between white (papas) and sweet potatoes (batata), but they were cultivated on the Canary Islands from 1565 and then onto the mainland of Spain.

|

|

|

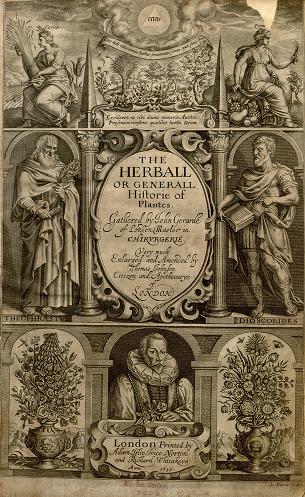

| The 1636 edition of Gerard's Herball. The author holds a spray of potato flowers in the illustrated title page of the book, seen in the bottom center, just above the imprint. The Cullman Library of the Smithsonian has two copies; this image is from the scanned copy in the Peter H. Raven Library of the Missouri Botanical Garden (from the catalog of the Biodiversity Heritage Library). |

|

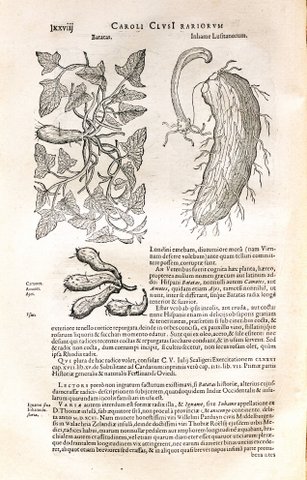

| Clusius' Rariorum plantarum historia (Antwerp, 1601). Images of the white and the sweet potatoes (above and below) from the scanned copy in the Peter H. Raven Library of the Missouri Botanical Garden by the Biodiversity Heritage Library (link). The Smithsonian's Cullman Library also has the title. |

|

| Clusius also created the first European representation of the potato, a lovely watercolor of 1588 of a plant in his garden. The work of art, with a note written by Clusius, is now in the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp (link here). |

In France, the tuber was particularly regarded as a poor person’s food. Sadly, the Smithsonian Libraries does not own a copy of the important Parmentier work, Examen chimique de la pomme de terre (Chemical examination of the potato, 1778). He was so successful in his efforts that some still believe he invented the potato, and there are many dishes named for him, such as the casserole of veal chops à la Parmentier.

By the 19th century, the potato was common and so prevalent that historians debate its exact role in fueling the population explosion of the period. The food stuff also was being put to other uses, such as in alcoholic spirits. John Ham’s The theory and practice of brewing, from malted corn and from potatos (London, 1829), is one such treatise. There are many gardening manuals in the Smithsonian Libraries that discuss all the types then being developed and best methods of growing and storage. William Cobbett’s The American gardener (London, 1821) has this charming entry:

"Potatoe – Every body knows how to cultivate this plant; and, as to its preservation during winter, if you can ascertain the degree of warmth necessary to keep a baby

from perishing, you know precisely the precautions required to preserve

a potatoe. – As to sorts they are as numerous as the stones of a

pavement in a large city."

But such dependency on a single crop, relied on by a huge population, proved ripe for disaster. This came in the form of late blight disease in the 1840s, which struck hard in Europe and was particularly devastating in Ireland. These catastrophes led to the development of disease-resistant plants, in particular by American horticulturist Luther Burbank who worked to improve the Irish potato; he bred a type in 1872 that established the Idaho potato. These new varieties led to even more potato dominance in food production and plantings around the world. It is a story likely to play out again with climate change, as scientists work to develop cultivars even more resistant to heat, drought and disease. To lessen pollution and water use and help feed its exploding population, China is now by far the largest producer of the staple in the world. Will the potato once again save some parts the world? (see Zuckerman, Larry. The potato: how the humble spud rescued the western world. Boston, 1998 and this Wikipedia entry on the subject).

|

| "Good seeds at fair prices": National Museum of American History Trade Catalogs of 1902 from Minneapolis, Minnesota (image from Wikimedia Commons of the copy in the National Agricultural Library) |

|

| An artist book in the collections: French fries : a new play, written by Dennis Bernstein, Warren Lehrer ; designed by Warren Lehrer, 1984. |

Julia Blakely

Special Collections Cataloger

Smithsonian Libraries

|

| An excellent dish for the month: Rainbow Potato Roast. |

For further reading:

Chilies to chocolate: food the Americas gave the world. Tucson, 1992.

Hawkes, J. G. The potatoes of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay: a biosystematics study. Oxford, 1969.

Ochoa, Carlos M. Las papas de Sudamérica. Lima, Perú, 1999.

Salaman, Redcliffe N. The history and social influence of the potato. Cambridge, 1985.

|

| Well, if you are going to have bacon with your potatoes, might as well have sour cream as well. Photo by the author but the great recipe and story from the New York Times. |

No comments:

Post a Comment