Modern museum management has moved into an interactive model emphasizing education and public engagement. In the past 15 years, collections management has been handled by using sophisticated Collection Information Systems (CIS) followed by quick publishing of most museum collections online for public searching and display.

Libraries, archives, and museums are considered complementary organizations that are making efforts to promote public education and engagement through their collections. Online catalogs and websites are expected to provide full and in-depth collection information that goes far beyond offering superficial eye-candy. These websites can now reach users around the world who may not be unable to visit the libraries, archives and museums physically.

Desire for a "One Stop" Search Online

The libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) at the Smithsonian used to maintain separate online catalogs within their respective professional fields. The Smithsonian has many museums, libraries, archives, a National Zoo, an Astrophysical Observatory, and several Science Research Centers. The Smithsonian’s subject areas cover arts and design, culture and history, science and engineering with 138 million collection objects. The Smithsonian has several hundred highly specialized database systems, websites, and catalogs. This should be a researcher’s information heaven, but trying to find the right information from the Smithsonian can be a challenge.

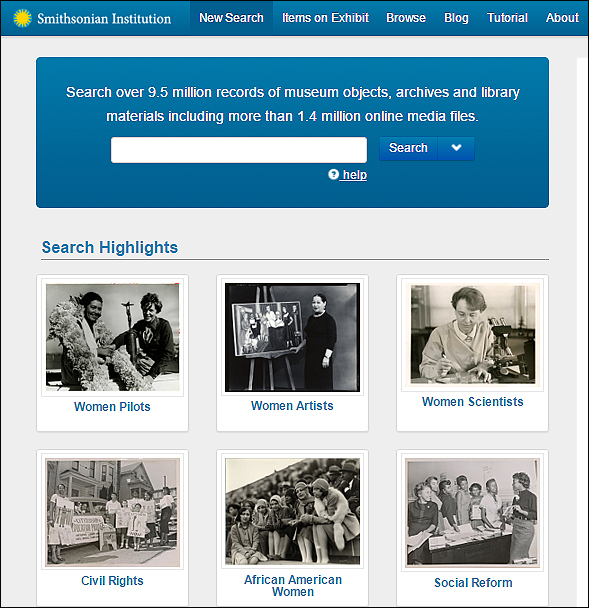

The solution was to create a “one-stop” search center that aims to include all online collections from the Smithsonian libraries, archives and museums. This Smithsonian's Collections Search Center (http://collections.si.edu) was launched in 2007 as one of the first large-scale single search center in the United States. It currently contains 9.5 million catalog records with 1.4 million images, sound files, and video recordings. These records describe books, journals, and trade catalogs from our libraries; photographs, manuscripts, letters, postcards, posters, sound- and video-recordings from our archives; and paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, decorative arts, ceramics, maps, portraits, scientific specimens, rockets, and airplanes from our museums.

The features of the Collections Search Center include keyword searching, filtering, various viewing options, slideshow, social media sharing, and a time-slider. The website is built to be mobile friendly.

The Collections Search Center only needs simple keywords to begin a search. The records returned in the search results are ordered according to the relevancy of the records to the search terms, with the best matched records listed at the top of the results list. Users can further enhance their search results by applying filters (faceted searching) by name, object types, subjects, time frame, geographical location, culture groups, scientific names, etc.

Once fully integrated into the Collections Search Center, the data from the Smithsonian's various databases works together in a harmonious fashion. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Desire for a "One Stop" Search Online

The libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) at the Smithsonian used to maintain separate online catalogs within their respective professional fields. The Smithsonian has many museums, libraries, archives, a National Zoo, an Astrophysical Observatory, and several Science Research Centers. The Smithsonian’s subject areas cover arts and design, culture and history, science and engineering with 138 million collection objects. The Smithsonian has several hundred highly specialized database systems, websites, and catalogs. This should be a researcher’s information heaven, but trying to find the right information from the Smithsonian can be a challenge.

The solution was to create a “one-stop” search center that aims to include all online collections from the Smithsonian libraries, archives and museums. This Smithsonian's Collections Search Center (http://collections.si.edu) was launched in 2007 as one of the first large-scale single search center in the United States. It currently contains 9.5 million catalog records with 1.4 million images, sound files, and video recordings. These records describe books, journals, and trade catalogs from our libraries; photographs, manuscripts, letters, postcards, posters, sound- and video-recordings from our archives; and paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, decorative arts, ceramics, maps, portraits, scientific specimens, rockets, and airplanes from our museums.

The features of the Collections Search Center include keyword searching, filtering, various viewing options, slideshow, social media sharing, and a time-slider. The website is built to be mobile friendly.

The Collections Search Center only needs simple keywords to begin a search. The records returned in the search results are ordered according to the relevancy of the records to the search terms, with the best matched records listed at the top of the results list. Users can further enhance their search results by applying filters (faceted searching) by name, object types, subjects, time frame, geographical location, culture groups, scientific names, etc.

Once fully integrated into the Collections Search Center, the data from the Smithsonian's various databases works together in a harmonious fashion. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Example 1: Search for Warren

Mackenzi’s pottery, we found many different material types in the search

result:

·

7 ceramic

objects from American Art Museum

·

13 books about

Warren Mackenzi and American potters from Library

·

3 interview

transcripts from Archives,

·

1 sound

recording of Oral History from Archives,

·

3 letters

written by Warren Mackenzi from Archives,

·

Two more

related collections from Archives,

|

Example

2: Search for Alexander

Calder as an artist, we found hundreds of objects from the following 10 Smithsonian

libraries, archives and museums:

|

|

·

National Postal

Museum (5)

·

Hirshhorn

Museum and Sculpture Garden (47)

·

Smithsonian

American Art Museum (30)

·

National

Portrait Gallery (10)

·

Cooper Hewitt,

Smithsonian Design Museum (8)

·

Photograph

Archives, Smithsonian American Art Museum (48)

·

Archives of American

Art (154)

·

Archives of

American Gardens (15)

·

Smithsonian

Institution Archives (9)

·

Smithsonian

Institution Libraries (164)

|

The Collections Search Center has been a great success! Diverse object types work well together because of several critical decisions we made during the project implementation process.

The Smithsonian chose to use a data-ingested model rather than a federated-searching model. This required creating special data extraction programs for every database at the beginning of the data aggregation process. All data sets had to pass through a required data standardization process. Even though this was a large amount of work up front for the system's designers, it provided reliable data quality and guaranteed search response time. This approach has turned out to be much better for the users.

We created a metadata model which served as the frame work for all the data processing. The metadata was based on national and international data standards that supports data types for bibliographic and archival materials, three dimensional objects and scientific specimens. We consulted several existing data standards used by libraries, archives and museums such as MARC, CDWLITE, MODS, Doblin Core, and VRA Core. In the end we narrowed down to fewer than 30 core data elements. This data model has proven to be lightweight, flexible, and scalable over the years.

The Smithsonian started this massive project with only limited databases in the early phase of the project. This allowed the project to focus on the data elements and data mapping without being overwhelmed. The project was eventually expanded to include collections data from more than 50 Smithsonian organizations and from 95 different databases and sources.

For anyone who considers similar projects, we can offer the following few lessons learned:

We created a metadata model which served as the frame work for all the data processing. The metadata was based on national and international data standards that supports data types for bibliographic and archival materials, three dimensional objects and scientific specimens. We consulted several existing data standards used by libraries, archives and museums such as MARC, CDWLITE, MODS, Doblin Core, and VRA Core. In the end we narrowed down to fewer than 30 core data elements. This data model has proven to be lightweight, flexible, and scalable over the years.

The Smithsonian started this massive project with only limited databases in the early phase of the project. This allowed the project to focus on the data elements and data mapping without being overwhelmed. The project was eventually expanded to include collections data from more than 50 Smithsonian organizations and from 95 different databases and sources.

For anyone who considers similar projects, we can offer the following few lessons learned:

- Start small and work with willing partners to build and demonstrate initial success.

- It is key to encourage participation from everyone within the organization, and to be respectful to their specific concerns while seeking solutions. It is also important to focus on collaboration over competition.

- Use national data standards to address data quality issues and minimize differences among data formats. Adherence to standards can help to defuse disagreements among staff from the different departments.

Looking Beyond the Smithsonian

In addition to the Smithsonian Institution’s successful project, there are other successful efforts to create single search systems around the world.

In addition to the Smithsonian Institution’s successful project, there are other successful efforts to create single search systems around the world.

In Europe, a coordinated effort created a “one stop search” portal called Europeana (http://www.europeana.eu/portal/). 37 countries joined in to contribute 39 million collection records from their libraries, archives, museums and cultural institutions. This internet portal serves millions of books, paintings, films, museum objects and archival records that have been digitized throughout Europe. In addition to searchable catalog records, multimedia files such as 23.3 million images, 507,000 sound files, 408,000 video files, 17,800 3D images and 15.2 million full text documents are available to the public. The Europeana portal attracts online visitors from more than 100 countries.

Trove, created by the National Library of Australia, is another great example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal for Australia. Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/ ) is a central online indexing system that includes more than 426 million books, images, historic newspapers, maps, music, archives records from 1500 contributing libraries, archives, museums, and cultural institutions. The National Library of Australia combined eight different online databases into a new single discovery interface. Trove's collection highlights include 136 million journals and research articles, 608,000 maps, 567,000 diaries, letters and archives records, 3.6 million music, sound and videos, 8 million photographs of objects, and 168 million digitized newspapers. Given such a large collection of rich information, Trove provides an easy way to filter a search by material types such as books, photographs, music and video files, maps, diaries and archives, websites, people and organizations.

One final example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal is the Digital Public Library of America in the United States. The discovery portal DPLA (http://dp.la/) is a union catalog for public domain and openly licensed content held by the nation's archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This is a fairly new system which was first launched in 2013, and it is still growing very fast. Records are contributed to DPLA following a model organized around "Content Hubs" and "Service Hubs". DPLA content hubs are large libraries, museums, archives, or other digital repositories that directly contribute large quantities of content to DPLA. DPLA service hubs are state, regional, or other collaborations that host, aggregate, or otherwise bring together digital objects from libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This model enables DPLA to collect a large number of quality records quickly. In just two years’ time, DPLA has already provided 10 million items from repositories across the United States. Organizations which have led the effort include Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and Records Administration, New York Public Library, California Digital Library, the J. Paul Getty Trust and others.

One final example of a coordinated “one stop search” portal is the Digital Public Library of America in the United States. The discovery portal DPLA (http://dp.la/) is a union catalog for public domain and openly licensed content held by the nation's archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This is a fairly new system which was first launched in 2013, and it is still growing very fast. Records are contributed to DPLA following a model organized around "Content Hubs" and "Service Hubs". DPLA content hubs are large libraries, museums, archives, or other digital repositories that directly contribute large quantities of content to DPLA. DPLA service hubs are state, regional, or other collaborations that host, aggregate, or otherwise bring together digital objects from libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. This model enables DPLA to collect a large number of quality records quickly. In just two years’ time, DPLA has already provided 10 million items from repositories across the United States. Organizations which have led the effort include Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and Records Administration, New York Public Library, California Digital Library, the J. Paul Getty Trust and others.Conclusion

One Stop search centers are important information search portals that build bridges among cultural institutions for all object types and materials. Their purpose is to serve the public and researchers to find the right information more easily through one-stop searching. Such search centers will only work if they are based on commonly shared data standards and controlled vocabularies. Hundreds of millions of catalog records have been created with quality data conforming to minimum standards, and these records have built up over a long period of time. A search center must be rich and deep in its contents, including images, sound and video files and full text documents, to attract and retain users. The success of the Smithsonian Collections Search Center should be measured by the usage rate of our featured objects and materials, and by the number of people who have consulted it online.

Creating a great single search center is complicated and takes a huge effort to succeed, but in the end, it is well worth the effort to create a collections discovery platform that the public will enjoy using.

Ching-hsien Wang, Project Manager for Smithsonian Collections Search Center

Collections Systems & Digital Assets Division, Office of the Chief Information Officer

No comments:

Post a Comment