American portraiture captures rich conversations between

artists, musicians, and singers. On the occasion of the Smithsonian’s Year of

Music, this essay explores the interplay of art, music, and portraiture in the

United States, from the Early Republic to today.

During the eighteenth century, artists were often inspired

to portray individuals and groups in the act of playing instruments or singing.

A popular theme was the informal family concert, which exemplified the harmony

and personal values shared by the represented members. An example is the

painting Family of Dr. Joseph Montégut (c. 1797-1800), which has been

attributed to José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza. It depicts a

French surgeon who has settled in New Orleans. He is surrounded by his wife,

great aunt, and children, who are about to play for their parents. Two hold flutes,

while a daughter’s hands are poised on the pianoforte keys. This composition of

a French Creole family in Spanish-governed New Orleans presents a vision of

musical and domestic harmony, which had precedents in European art tradition. https://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-museum/collections/visual-art/artists/jos-francisco-xavier-de-salazar-y-mendoza

From the 1790s through the 1830s, theater and concert

performances proliferated and by the mid-nineteenth century, music had become a

public commodity. A leading European virtuoso, the Swedish singer Jenny Lind, toured

the United States from 1850-1852, in part with the sponsorship of P.T. Barnum. Many

American artists portrayed the popular “Swedish Nightingale,” including Francis

Bicknell Carpenter, whose 1852 oil painting depicts Jenny Lind in costume,

holding a musical score book.

Jenny Lind by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, oil on canvas, 1852. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Eleanor Morein Foster in Honor of First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton (NPG.94.123)

From 1892 to 1895, the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák was director of the National Conservatory of Music in

America. His famous symphony From the

New World (1893) reflected his interest in African American and Native

American music. He promoted the idea that American classical music should

follow its own models instead of imitating European composers. Dvořák

helped inspire our composers to create a distinctly American style of classical

music. By the twentieth century, many American composers, such as Leonard

Bernstein, Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, and Charles Ives incorporated diverse

musical genres into their compositions, including folk, jazz, and blues.

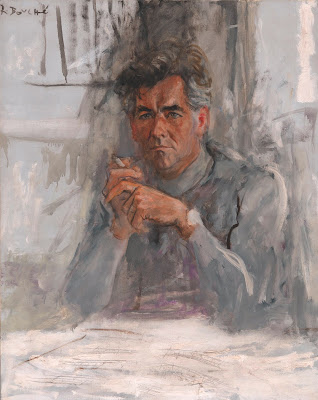

As a composer, pianist, and conductor, Leonard Bernstein made

a profound impact on American music by collaborating with the performing arts. His

interests ranged from classical music and ballet to jazz and musicals. In an

oil portrait of 1960, René Robert Bouché portrayed Bernstein in a moment of

reflection, with the papers of the musical score he is writing scattered across

the desk in front of him.

Leonard Bernstein by René Robert Bouché, oil on canvas, 1960. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Springate Corporation. © Denise Bouche Fitch (NPG.92.3)

The composer George Gershwin and his brother, lyricist Ira

Gershwin, were also highly versatile, having collaborated on popular musicals

and a folk opera. Both brothers also painted interesting self-portraits, which

can be viewed in the Gershwin collection in the Music Division of the Library

of Congress. In a 1934 oil portrait in the collection of the National Portrait

Gallery, George Gershwin represented himself in profile with a musical score

and his hand alighting upon the piano keys.

Self-Portrait by George Gershwin, oil on canvas board, 1934. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Ira Gershwin. © Estate of George Gershwin (NPG.66.48)

The following year, the Gershwin brothers debuted Porgy

and Bess, “an American folk opera,” which broke new ground in musical

terms. Soprano Leontyne Price appeared in the 1952 revival touring production

of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, which brought her first major success. Less

than a decade later, in 1961, Price became the first leading African-American

opera star when she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera. Bradley Phillips

created this formal oil painting of Leontyne Price within a stage setting in

1963. It is one of several portraits he made of the singer. The artist

expressed the admiration he felt for her immense talent when seeing her perform

onstage.

Leontyne Price by Bradley Phillips, oil on canvas, 1963. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Ms. Sayre Sheldon (NPG.91.96)

Artists Thomas Eakins and George P.A. Healy also created portraits

of singers and musicians. In the medium of painting, these artists were able to

convey the intensity and precision of the musicians in their performances. Thomas

Eakins asked his model Weda Cook to repeatedly sing a particular phrase from

Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah, so

he could explore the position and movement of her mouth and vocal chords for

his portrait Concert Singer (1890-1892).

In this manner, he recreated the immediate sense of a formal concert with the contralto

singing on the stage and the conductor’s hand and baton raised in the lower corner.

https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/42499.html

George P.A. Healy visited virtuoso Franz Liszt in Rome and created

this 1868-1869 oil portrait of him playing the piano in an inspired moment. Healy

even convinced the composer to allow Ferdinand Barbedienne to cast his hands in

bronze, an artifact Healy later kept in his studio. https://callisto.ggsrv.com/imgsrv/FastFetch/UBER1/ZI-9HFT-2014-JUN00-SPI-142-1

Both artists not only portrayed the physical characteristics of musicians and

singers but also the inner passion and mental concentration they brought to

their performances. As such, they recreated the emotional spirit of the music

for viewers.

James McNeill Whistler thought about his paintings in terms

of musical titles and themes. He created not only portraits of musicians but also

discussed the subtle tonalities of his more abstract urban scenes and landscapes

in musical terms. In 1878, Whistler defended the titles of his paintings: “Why

should not I call my works ‘symphonies,’ ‘arrangements,’ ‘harmonies,’ and ‘nocturnes’?...As music is

the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter

has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of colour.” This analogy between

music and painting was Whistler’s primary means for defending his paintings

against criticism. Indeed, he published this defense in the journal The World during his libel lawsuit

against critic John Ruskin, who referred to Whistler’s 1875 oil painting of

fireworks in London, Nocturne in Black

and Gold: The Falling Rocket, as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s

face.” https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/nocturne-black-and-gold-falling-rocket-64931

Whistler’s use of music as a metaphor for painting was intended to build

support for the concept that color, form, and painterly technique were the

primary elements of an artwork. Whistler brought this correlation of painting

and music to public attention with his artworks, which in turn influenced other

artists and musicians.

Regional painter Thomas Hart Benton praised “James McNeill

Whistler[’s art]...tone, colors harmoniously arranged…Whether you can

distinguish one object from another or not, whether the thing painted looks

like a man, woman, or dog, mountain, house or tree, you have harmony and the

grandest artistic aim, it is the truly artistic aim.” Benton was a self-taught

and performing musician who invented a harmonica tablature notation system used

in current music tutorials. He was also a cataloguer, collector, transcriber,

and distributor of popular music. He had musical gatherings for family and

friends at his home in Kansas City. These sessions were commemorated on a 1942 recording

by Decca Records called Saturday Night at

Tom Benton’s, which featured chamber and folk music. Benton’s friend, the

popular actor and singer Burl Ives, shared his passion for American songs.

During the Great Depression, Ives traveled the country gathering and playing

folk songs, and Benton made sketches of folk musicians in different regions. In

a 1950 lithograph titled the Hymn Singer

or the Minstrel, Benton portrayed

Ives playing the guitar.

Burl Ives by Thomas Hart Benton, lithograph on paper, 1950. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY (NPG.85.141)

In 1973, Benton was commissioned to paint his last mural, The Sources of Country Music, for the

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, with support from the

National Endowment for the Arts. He decided the mural “should show the roots of

the music–the sources–before there were records and stars,” and he created a

lively, flowing composition of country folk musicians, singers, and

dancers. https://www.arts.gov/about/40th-anniversary-highlights/thomas-hart-bentons-final-gift

Artist LeRoy Neiman featured Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong,

Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Benny Goodman, and other

famous jazz performers in his group portrait Big Band (2005), which is held at the Smithsonian National Museum

of American History. It took Neiman ten years to complete this mural-size

tribute to eighteen jazz masters, which the LeRoy Neiman Foundation presented to

the Smithsonian after the artist’s death in 2012. Neiman frequented jazz clubs,

where he befriended and sketched these performers. In 2015, the LeRoy Neiman

Foundation donated funds to the Smithsonian towards the expansion of jazz

programing during the annual celebration. See the following two part guide to

this group portrait of jazz greats: https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/neiman-jazz

and https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/neiman-jazz-2

One can discover further portraits and biographies of

notable composers, musicians, and singers in the Catalog of American Portraits

(CAP). In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the CAP, a

national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from

the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the

online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s

website: https://npg.si.edu/portraits/research/search

The Smithsonian is celebrating the Year of Music with a wide

variety of collection highlights and programs. To learn more, please visit: https://music.si.edu/smithsonian-year-music

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Bibliography:

Cheek, Leslie Jr., Director. Souvenir of the Exhibition Entitled Healy’s Sitters. Richmond:

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1950.

Coleman, Patrick, ed. The

Art of Music. San Diego, CA, and New Haven, CT: San Diego Museum of Art in

association with Yale University Press, 2015.

Fargis, Paul, and Sheree Bykofsky, et al. New York Public Library Performing Arts Desk

Reference. New York, NY: Stonesong Press, Inc., Macmillan Company, and New

York Public Library, 1994.

Fortune, Brandon. Eye

to I: Self-Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery. Washington, D.C:

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Munich: Hirmer Verlag,

2019.

Gontar, Cybèle, ed. Salazar: Portraits of

Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785-1802. New Orleans, LA: Ogden Museum

of Southern Art and University of New Orleans Press, 2018.

Henderson, Amy, and Dwight Blocker Bowers. Red, Hot and Blue: A Smithsonian Salute to

the American Musical. Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery and

National Museum of American History, in association with the Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1996.

Kerrigan, Steven J. “Thomas Eakins and the Sound of

Painting.” Paper presented at the James F. Jakobsen Graduate Conference,

University of Iowa, 2012. https://gss.grad.uiowa.edu/system/files/Thomas%20Eakins%20and%20the%20Sound%20of%20Painting.pdf

Mazow, Leo G. Thomas

Hart Benton and the American Sound. University Park, PA: Penn State University

Press, 2012: http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-05083-6.html

.

Ostendorf,

Ann. “Music in the Early American Republic.” The American Historian (February 2019): 1-8.

Phillips, Tom. Music

in Art: Through the Ages. Munich and New York, NY: Prestel-Verlag, 1997.

Struble, John Warthen. History

of American Classical Music: MacDowell through Minimalism. New York, NY: Facts

on File Publishers, 1995.

Walden, Joshua S. Musical

Portraits: The Composition of Identity in Contemporary and Experimental Music.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Wilmerding, John, ed. Thomas

Eakins. Washington, D.C. and London: National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1993.

No comments:

Post a Comment