|

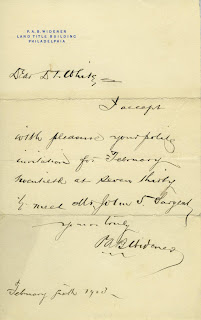

| P.A.B. Widener's dinner invitation acceptance. |

This summer, it’s been part of my internship at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives to answer these questions as I process the collected correspondence of art historian Thomas Brumbaugh. Sifting through yellowed, crinkly papers filled with hard-to-read loopy handwriting may seem like a painful way to spend one’s summer, but it has been anything but. Every letter is a gem in this treasure chest of historical value, whether it’s the acceptance to dinner with John Singer Sargent from millionaire P.A.B. Widener, or the sweet, half-finished thank-you letter from American painter Abbott H. Thayer’s young son Gerald Thayer.

Thomas Brumbaugh began collecting correspondence and signatures in his youth, and continued throughout his teaching and publishing career at Vanderbilt University on topics concerning American art and artists. Thanks to his eagle’s eye for diamonds in the rough that would augment the worth of the collection, Brumbaugh managed to acquire letters from a number of famous figures in the 19th and 20th century American art scene, including Thayer, Widener, George de Forest Brush, Samuel Coleman, and Maria Oakey Dewing.

|

Thayer's letter to his late wife's sister, Gertrude, alerting her to his new marriage. |

But the collection doesn’t just concern artists. Through it, I encountered quite a few letters from military personages, including correspondence regarding the renovation of the United States capitol, and letters from Abraham Lincoln’s Quartermaster, Montgomery Meigs. The Thomas B. Brumbaugh collection of 19th and 20th century American artists' correspondence doesn’t simply give the researcher a lopsided, art-focused view of those years, it paints a beautiful, multi-dimensioned picture of the time, covering everything from formal commissions for paintings to friendly invitations to dinner; from plain scenes of daily life to heart-wrenching appeals for forgiveness. I’ll assure you one thing about this collection, and that’s that you’ll end up reading quite a few more letters than you intended to.

Although I have since moved on to other collections, I can still visualize the wobbly, all-caps lettering of sweet Gerald Thayer, and the elegant, curving script on an order for “fancy chairs” from the 1800s. So are letters still relevant in this technology-driven 21st century? I say definitely. I know that since processing this collection, I have endeavored to send more letters, write more entries in my journals, and save as many scraps of paper that I use as possible. Is it self-important to already prepare for the poor archivist that will have to process my papers? Perhaps. But is it terribly fun to picture an overwhelmed intern, eighty years from now, being shocked at my poor life choices, awed at the amazing people that I ate dinner with, or just plain confused as to why my unimportant self is even included in a collection.

For collection records and image galleries from this collection, click here.

-- Beatrice Kelly, intern, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives

For collection records and image galleries from this collection, click here.

-- Beatrice Kelly, intern, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives

Fascinating! I needed to view a sample of handwriting by Thayer to ID a piece of art I found and this is the perfect resource. Thanks for posting!

ReplyDeleteTina I am so glad we could be of service! Thanks for your thoughtful note,

ReplyDeleteRachael Woody

Rachel, I am interested to learn of any tools you may have used to help decipher some of the handwriting you encountered processing this collection.

ReplyDeleteThanks,

Penny