|

Before (top) and after (bottom) conservation

of a page from Dorsey’s “Comparative Dakota,

Ponca (and Omaha), Osage, Quapaw, Kansa,

Winnebago, Iowa, Mandan, Hidatsa, and

Crow vocabulary 1877” (MS 4800[81]) |

As with all archives, access is fundamental to the mission of the

National Anthropological Archives (NAA). With new support from the Arcadia Fund, the NAA will be working over the next two years on preserving and providing wider access to a treasure trove of primary sources used to investigate endangered language and cultures. This funding will support the digitization of the NAA’s entire sound collection (close to 3,000 recordings) and 35,000 pages of manuscripts. Although an impressive 100,000 digital resources are accessible online, this is still less than one percent of the Archives’ manuscript materials and five percent of sound recording holdings.

The origins of language documentation collections at the National Anthropological Archives begin with the founding of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) in 1879. The first research program in the U.S. devoted to the methodological study of Native Americans, the Bureau engaged an extensive network of researchers in highly-systematic data collection to record the past and present ways of life of the North American tribes. Researcher field notes, photographs, and sound recordings document the language, culture, and knowledge of hundreds of indigenous communities throughout the Americas. Language documentation was a major focus of the BAE from its inception, assembled through field work and collecting earlier manuscripts, such as notes from the philologist Horatio Hale, who sailed around the world with the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838-42. Later collections reflect a broader interest in languages as the archives' mission expanded to include preservation of historically valuable records documenting cultures worldwide.

Sound recordings in NAA’s collection contain the poetry, songs, stories, and conversations of endangered language communities around the globe. Approximately half of the recordings were made in North America; the remaining 1,500 contain roughly equal amounts of material from Africa, Oceania, and South America. Much of the North American material was recorded early in the 20th century, while documentation from other regions dates primarily from the 1950s through the 1970s. These materials are on various obsolete and endangered media, ranging from wax cylinders and aluminum transcription disks to various sizes and speeds of magnetic tape. Digitization will move them to the latest standards of electronic media, with provision for regular migration as standards change over time.

|

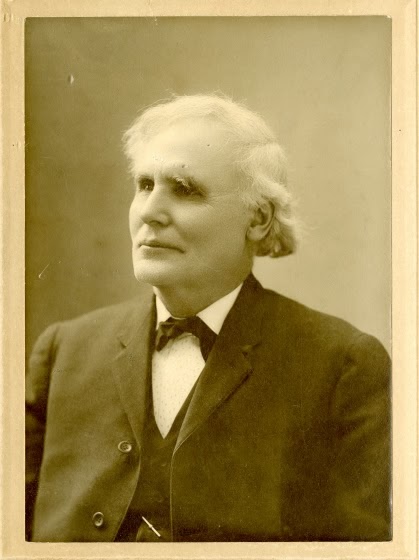

Dorsey_01.jpg: The Reverend James Owen Dorsey, n.d.

To digitize ALL of the Dorsey collection

(67 boxes with an average 200 pages per box)

will take a minimum of three (3) months of full-time work. |

The grant will also support the digitization of 20,000 heavily-used linguistic manuscript materials, at a critical point of deterioration. Two of the most used and fragile linguistic collections selected for digitization within the NAA are the papers of

Truman Michelson and

James Dorsey. Michelson, an esteemed early 20th-century linguist, assembled his materials while documenting the Algonquian languages of North America. Feel free to peruse some of the Truman Michelson PDFs we have made

available in SIRIS. Thousands of pages of texts, many written by the first generation of literate Native people, constitute a systematic record of fourteen separate languages, with an excellent representation of different types of Native texts, ranging from personal biographies to historical narratives and ceremonial precepts. The majority of the Michelson material was written on cheap tablets made with highly acidic paper that is now at a critical point of deterioration. Dorsey’s material, assembled in the late 19th century, is primarily devoted to Siouan languages. His papers provide an unprecedented record of a dozen languages from a time when they were widely spoken. Both collections are threatened resources, making the timing of the generous funding from Arcadia particularly important.

We’ll be working hard to get these digitized sound recordings and manuscripts up online in the

Collections Search Center, so stay tuned!

Lauren Marr, Program

Assistant

with support from the

NAA project team