Blogs across the Smithsonian will give an inside look at the Institution’s archival collections and practices during a month long blog-a-thon in celebration of October’s American Archives Month. See additional posts from our other participating blogs, as well as related events and resources, on the Smithsonian’s Archives Month website.

Sometimes hidden connections are hanging in plain sight. The

Wiseman-Cooke airplane, flying high above the atrium at the

National Postal Museum, is an example of ties between Smithsonian museums. Not only does this aircraft, on loan from the

National Air and Space Museum, hold an important place in the history of aviation, it also played an important role in postal history.

|

| Wiseman-Cooke airplane on display in the Smithsonian's National Postal Museum. |

The invention of the airplane offered a faster alternative to delivering mail, but air mail deliveries initially were private matters and not available to the general public. For example,

Glenn Curtiss carried a letter from the mayor of Albany to the mayor of New York City on his famous

May 29, 1910, flight down the Hudson.

Fred Wiseman, from Santa Rosa, California, had worked in a bicycle shop before he got into automobile racing. On a trip to Dayton, Ohio, in 1909, he visited with a duo who had also worked in a bicycle shop—Orville and Wilbur Wright. Upon returning to the west coast, Wiseman persuaded a fellow car racer, M.W. Peters, to combine their racing winnings with a local butcher, Ben Noonan, to build an airplane. When the aircraft was completed in the spring of 1910, it became the first California-built aircraft to fly.

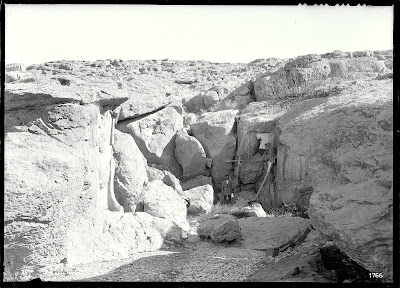

Wiseman built two aircraft along the same design model, combining elements of Wright, Curtiss, and Farman designs. The second aircraft is most likely the one that flew at an air meet at

Selfridge Field (the former Tanforan race track) near San Bruno. Wiseman placed second in the novice class, won the distance event, made the longest sustained flight, and accumulated the most total time in the air.

|

| Wiseman aircraft at Tanforan meet, Selfridge Field, San Francisco, California, 1910. Wiseman signed the photograph later. NASM A-42344-A |

On February 17, 1911, Fred Wiseman accomplished what he is best known for—the first air mail flight officially sanctioned by a post office and available to the general public. He flew from Petaluma (where he was doing most of his flying) back to his hometown of Santa Rosa. He carried letters from the mayor and postmaster of Petaluma to their Santa Rosa counterparts and fifty copies of the newspaper. He also delivered a letter from

George P. McNear, member of a prominent Petaluma family whose interests included the Sonoma County National Bank and the Petaluma and Santa Rosa Railroad, to John P. Overton, president of the

Savings Bank of Santa Rosa.

Petaluma is approximately 18 miles north of Santa Rosa, a quick, easy distance under modern standards. But Wiseman’s flight was anything but easy. Weather delayed his initial takeoff by days. Only 4.5 miles into the flight, he developed magneto trouble and was forced to land in a field, narrowly avoiding a windmill. Although his ground crew was able to fix the engine, due to winds, he needed to wait until the next day to take off from a makeshift canvas runway. The flight ended abruptly one mile outside of Santa Rosa when a loose wire caught in the propeller, forcing him down for good. He spent an estimated 16 minutes total in the air.

Wiseman continued to fly exhibition shows up and down the west coast through 1911, but it became expensive to ship the aircraft. He sold the aircraft to Weldon Cooke in 1912. Wiseman returned to his career in cars and worked as an automotive engineer for Standard Oil. Cooke first flew the plane in an Oakland air meet in February, but the engine suffered a broken crankshaft and did not place. Cooke continued to fly in this aircraft, with his own modifications, until his death in another aircraft in Pueblo, Colorado, in September 1914.

|

| Fred Wiseman returns to the cockpit of his aircraft, circa 1947. NASM 79-687 |

The Wiseman-Cooke aircraft (called so due to the Cooke modifications) sat in Cooke’s brother’s storage until it was loaned for display in the Oakland Airport in 1933. In 1948, the Smithsonian Institution acquired both the Wiseman-Cooke aircraft and Cooke’s

Maupin-Lanteri Black Diamond.

In addition to the actual aircraft, the National Air and Space Museum also has historical documents about the Wiseman-Cooke aircraft in the

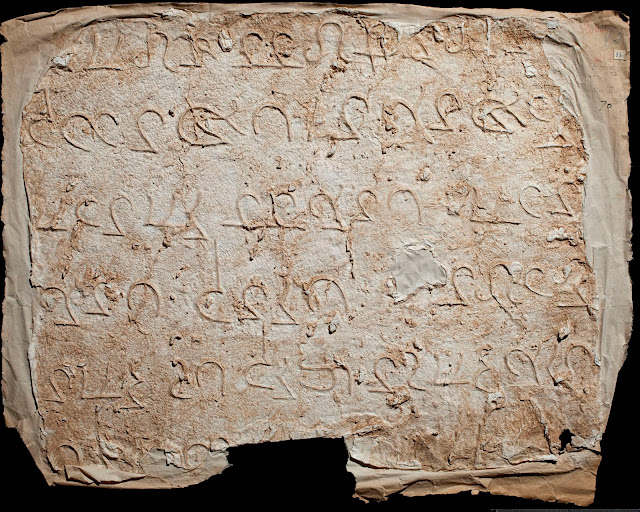

Archives. The fragile

Fred Wiseman Scrapbook (Acc. No. XXXX-0618) contains Wiseman’s correspondence, particularly from the 1940s and 1950s concerning his flight, and newspaper articles from the 1910s. The

Weldon B. Cooke Collection (Acc. No. 1998-0001) features newspaper articles and photographs relating to Cooke and the various aircraft he built or flew.

|

| Fred Wiseman Scrapbook in its acid-free storage box, with ethafoam spacers. NASM 2015-06149 |

|

| Pages from Fred Wiseman scrapbook. Note the correspondence from the Smithsonian Institution (left page, center). NASM 2015-06150 |

The very next day after Wiseman’s flight, Henri Pequet flew mail between Allahabad and Naini in India. The

first air mail flight sanctioned by the United States Post Office was flown by Earl “Ovie” Ovington on September 23, 1911, when he flew a bag of mail from Garden City to Mineola on Long Island. On May 15, 1918, the first continuously scheduled air mail route in the United States opened between Washington, Philadelphia, and New York.

Elizabeth C. Borja

Archivist, National Air and Space Museum Archives