|

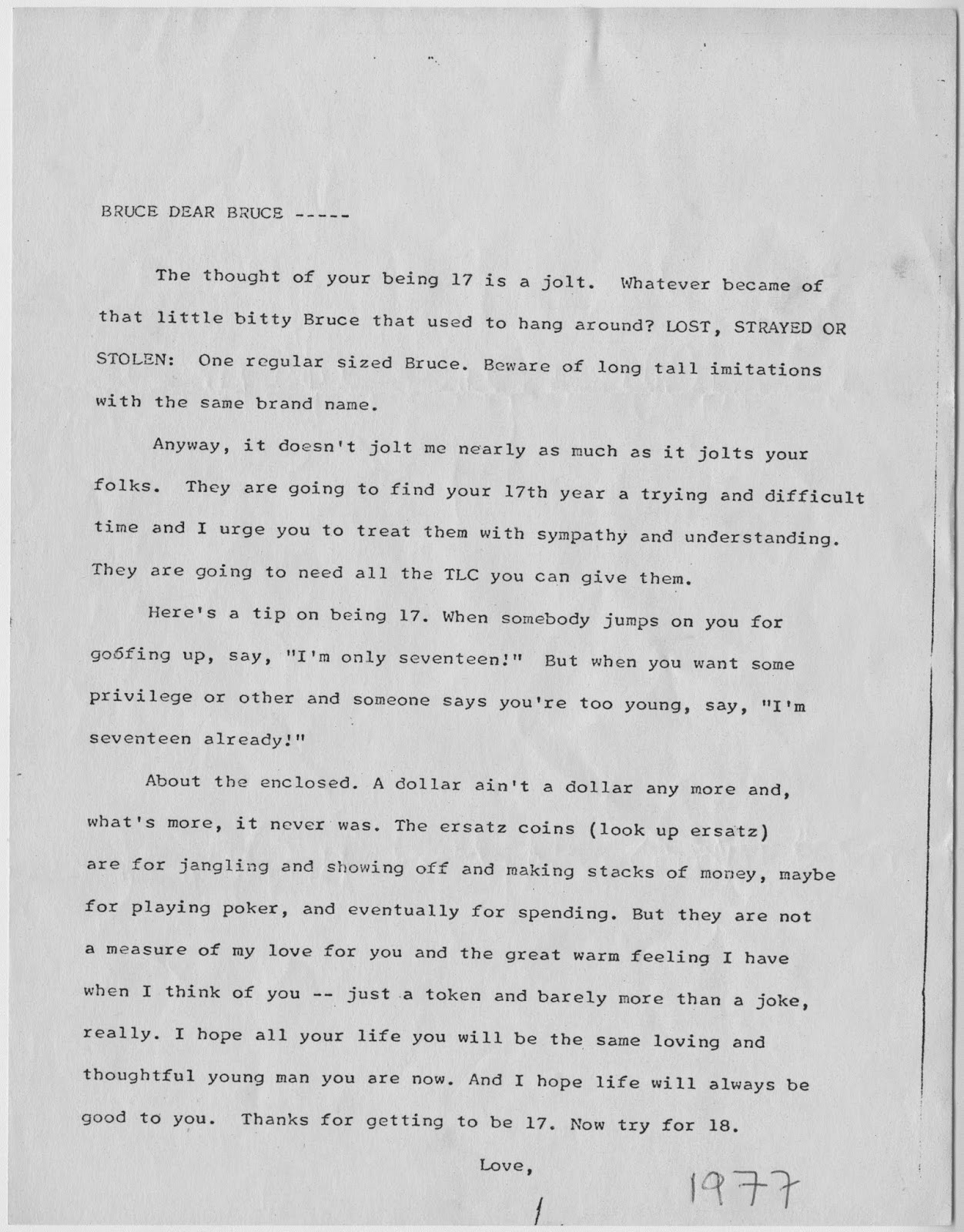

| Announcement for a Slocum lecture at Everett House, New York (undated; NAA INV 02881600, photo lot 70, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution) |

Every now and then,

maritime historians of the National Museum of American History have to

address the

belief that the vessel

Liberdade of renowned sailor, Joshua Slocum (1844-1908?*), is buried in storage somewhere in

the Smithsonian.

Slocum designed and built the boat following

the wreck of the Aquidneck, his

coastal trading bark, which left him, his wife and two sons stranded in South

America. Using lumber and fastenings salvaged from the wreck, and local timber,

he built a 35-foot-long, six-ton, sea-going canoe, beam of seven and a half

feet and draft of three feet. The small cabin, covered only by a canvas tarp,

was home to the Slocum family for the entire voyage of an

incredible 5,500 miles. Liberdade journeyed from Brazil ending up the Potomac River in Washington,

D.C., of all places, in 1888.

Slocum's model for the boat came

from his memory of the Cape Ann dories of New England, modified by a photo he

had on hand of a Japanese sampan. "As might be expected, when finished,

she resembled both types of vessels in some degree" he wrote. He rigged

the boat in the Chinese sampan style, "which is, I consider, the most

convenient boat rig in the entire world.” His wife made the sails.

Liberdade, built

with local help and launched on the day slaves were declared free in Brazil (hence

the name) was indeed exhibited for a time at the Smithsonian. But first, after wintering

in the nation’s capital (until 1889), the family made their way up to New York

and then on to New England, receiving much attention all along with way for their adventure.

Slocum, his career as a commercial captain over after a series of mishaps and outright

disasters, wrote about the journey as a means to support his family. Slocum

brought the

Liberdade back to

Washington, keen on self-promotion, leaving the unique vessel to be viewed, outdoors.

With the pressing need for space due to rapidly growing collections and not

wanting to destroy the deteriorating boat (despite the Captain’s permission), Smithsonian

officials urged Slocum to return to Washington to take re-possession. In December

1906, he brought the

Liberdade—beginning

to rot away although the Captain intended to save the planks and rib to rebuild

—to a boatyard on the Potomac River.

Some pieces were given away to spectators but no relic is currently identified,

anywhere, including the Smithsonian collections. And no record of the last of

the

Liberdade is known. As it

happens, there is not even a cataloged copy of Slocum’s account of the journey,

The Voyage of the Liberdade (Boston, 1890)

in the Smithsonian Libraries.

|

| Collection of the author |

There are, however, other tangible objects in various Smithsonian collections associated with Slocum most famously the first to circumnavigate the globe single-handedly. Links to this important figure in maritime and literary history can be readily found thanks to catalogs and online databases from sources both within and outside the Institution, with their relevant information and images. They provide a fuller picture of the Captain – or at least of this curious and remarkable episode with a boat he made himself.

In the age of the

decline of sail, Slocum left Boston in April 1895 on the

Spray, a rebuilt and entirely reconfigured oyster sloop. A superb sailor and navigator, he had 46,000 miles

under

Spray’s keel when he completed

his astounding circumnavigation in

Newport,

Rhode Island, and then onto his home port in Fairhaven, Massachusetts in June

and early July of 1898.

From this epic voyage, Slocum penned that classic of travel

literature and adventure,

Sailing Alone Around

the World. It is a lyrical book, and the 37-foot

Spray, is a trusted companion throughout:

March 31 the fresh southeast wind

had come to stay. The Spray was

running under a single-reefed mainsail, a whole jib, and a flying-jib besides,

set on the Vailima bamboo, while I was reading Stevenson’s delightful ‘Inland Voyage.’ The sloop was again doing her work smoothly, hardly rolling at all,

but just leaping along among the white horses, a thousand gamboling porpoises

keeping her company on all sides.

|

| Title page with Professor Mason's signature |

The story was initially published in serial form from September

1899 to March 1900 in

The Century Magazine; the first edition of

Sailing

Alone Around the World came out in 1900. Having read the book only in paperback

form, I was delighted to catalog the 1900 imprint in the

Cullman Library (

G440.S628 1900 SCNHRB). It was a presentation from the author to his friend

Otis Tufton Mason (1838-1908), Curator of Ethnology at the

Smithsonian, who helped to have Slocum take away the

Liberdade. Unlike Slocum’s previous writings,

Sailing

Alone was a great

success and still resonates, beloved of

maritime writers and "live-aboards".

Sailing

Alone was a best seller and made the captain a celebrity. For a fee, rather sadly,

Slocum had the

Spray hauled up the

Hudson River and Erie Canal to Buffalo, New York for the extravagant Pan-American

Exposition of 1901, to capitalize on his hard-won popularity. As related to

Mason, Slocum intended to refit the

Liberdade

with an engine for the towing to Buffalo but couldn’t manage to get to Washington in time. For this World’s Fair, a “Special Pan American Edition” of

Sailing Alone was issued and his wife,

Henrietta Slocum, produced a pamphlet,

Sloop Spray Souvenir, with a piece of the boat’s mainsail tipped-in. Despite the dozens and dozens of printed materials from the

Pan-American Exposition,

Sloop Spray

Souvenir is not in the Smithsonian Libraries’ collections. There is a copy

of this rare title nearby though, in

Georgetown University’s Special Collections archives.

|

| The Millicent Library's copy with a fragment of Spray's sail |

|

| Card catalog in the National Anthropological Archives |

Slocum returned to Washington in early 1902 when he went to

the White House to talk to President Theodore Roosevelt of his adventures. Carried

back on the

Spray during that trip are

a few items now in the Anthropology Department of the National Museum of Natural

History: stone and

shell axes,

one procured from a “colonial resident” in New South

Wales, Australia, and

another from (perhaps) New Guinea. These artifacts were

probably presented by Slocum to Mason, who, along with George Brown Goode, did

much to reorganize and display the collections in the then-new United States

National Museum. Despite lacking much of

a formal education in his native Nova Scotia, Slocum likely sensed a kindred

spirit in Mason, who was born nearby, in the remote seafaring islands of

Eastport, Maine (although he did not grow up there) and their shared interest in anthropology.

|

| Otis Tufton Mason (photo Wikimedia Commons, originally from Popular Science Monthly, vol. 74, January 1909) |

|

But another, later Smithsonian curator,

Howard I. Chapelle

(1901-1975), was among Slocum’s critics and suggested that

Sailing Alone was ghost-written. Slocum had earlier publications,

long before his fame, including

Rescuing

Some Natives of the Gilbert Islands in 1883 (

VK1424 .G46 S63 ANTH). Although

largely self-educated, Slocum was well-read (his publisher stocked a library on

Spray) and it is hard to imagine that

the good humor and dry wit of his descriptions, where the ocean is never

portrayed with malice, could have any author other than Slocum.

Chapelle was a nautical architect and in the abstract for the catalog

record on the thorny “

Constellation Question” is described as “as

straightforward as he is learned” (SILSRO 113108). The author of several works,

including

American Small Sailing Craft

(1951

; VM351 .C481 NMAH), Chapelle sought to show that

Spray

could be easily capsized and not be righted if rolled. However, he found in his

analysis that she was stable in most conditions.

There are other associations of Captain Slocum’s in the

Smithsonian. The Botany Department has at least one specimen from his various nautical wanderings:

Encycliakingsii (C.D. Adams) Nir (Caribbean). He had presented President Roosevelt with a

rare orchid before taking the President's son, Archibald, sailing on

Spray from Oyster Bay, Long Island. Impressed with the child's natural nautical talent, Slocum later considering presenting Archie with the

Liberdade (wherever it was at that time). And as quoted in the biography,

The Hard Way Around, Slocum wrote the Smithsonian a letter of February 1901 "requesting that if and when a 'flying ship' were launched, 'I could have a second mates position on it to soar.'" With his circumnavigation, he had already helped shrink the world.

|

Frontispiece of Sailing Alone (Cullman Library copy)

Illustrations in this first edition are by Thomas Fogarty and George Varian |

Slocum never flew and his story does not end well. Black clouds and legal troubles

followed him through life; sadness and despair could only be managed at sea. Trying

to settle in a house and farm on Martha’s Vineyard after his circumnavigation,

Slocum was soon restless and embarked on

shorter solo trips. Inevitably, he set off again in 1908,

both he and

Spray deteriorating, with

the intention of sailing to South America to find the source of the Amazon. Neither

was seen again.

Julia Blakely

Smithsonian Libraries

*Slocum's death date is often cited as 1909, when he was legally declared dead. See Geoffrey Wolff's The Hard Way Around (New York, 2010; p. 212) for why the date should be 1908.