| Image from: Richard Kenneth Saker Photographs of Tibet, 1942-1943 |

Monday, January 30, 2012

Smithsonian Snapshots: Larger than Life

This photograph of four beautiful statues of the Buddha was taken in the early 1940's by Richard Kenneth Saker, a British Trade Agent posted to Gyantse, Tibet. To get a sense of the scale of these statues, look for the photographer's lighting assistant in the lower right corner. We don't have much detailed information about Saker's photographs and film; if you know where this one was taken, let us know in the comments!

Karma Foley, Human Studies Film Archives

Thursday, January 26, 2012

The People of India - The Bhats

The People of India series was researched and written by School Without Walls student, Cal Berer. Cal was an intern at the Freer|Sackler Archives from January 2011-June 20011 where he was then sponsored by the State Department to learn Hindi while spending the summer in India.

The Bhats

The Bhats are an especially interesting tribe. Unlike most, they didn’t occupy a single ancestral homeland, or even several. Instead, they wandered throughout the country, as the Indian equivalent of minstrels and bards. Among the bard Bhats there are two categories: the Birru-bhats and Jaga-bhats. The former were hired out occasionally to sing at festivals and family ceremonies, while the latter served a single family for generations, and function as its historians, visiting the members from time to time to record significant events. However, the most interesting aspect of Bhat culture is this: “Among all the classes and tribes in which the crime of dacoity is followed as an hereditary profession, there is none whose proceedings are characterized by such boldness and skill as the Bhats.” It seems that, in addition to the true minstrel Bhats, a separate clan of Bhat dacoits existed, claiming the same ancestry as their nonviolent counterparts, and using musical recitation as a front to tactfully conceal their real profession. The modus operandi of these sinister Bhats is both chilling and fascinating. Their crimes were nearly always directed towards wealthy bankers and sahukars. Because most Bhats had no permanent residence, bands would travel from town to town, posing as musicians, while their most seasoned members ascertained the location of potential victims. Then, after a target is selected, the Bhats would proceed to make camp some 50 or 100 miles away, and then assemble near the site of their attack. The attack itself always took place at twilight, as a matter of tradition. The doors would be broken down, the house stormed, and any resistors brutally killed without hesitation. Upon raiding the home of its valuables, the gang would retreat from town to their camp, where the spoils would be divided. It should be said that, although barbaric and cruel, the dacoit Bhats never killed indiscriminately; only resistance warranted deadly violence. By the time POI was published, these bandit Bhats were almost entirely extinct, the remnants driven into hiding the by arrest, execution, or deportation of their fellows. Still, they are a morbidly romantic part of India’s tribal history. One might say they were to the subcontinent as the legendary highwaymen were to Victorian England: morally bankrupt, yet roguishly endearing.

To see all text and images of the Bhats as they are represented in the People of India, go to our catalog in the Collections Search Center.

The People of India series will be published once a month highlighting the various tribes as they're covered in the People of India.

Cal Berer, Intern

Labels:

Anthropologists,

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives,

History and Culture,

Photographs,

The People of India Series

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

House Hunting

|

The Gleason Garden, circa 1960-1967.

A view of the patio with outdoor furniture and a grill.

Photograph by Molly Adams.

|

|

The Gleason Garden, circa 1960-1967.

Looking from the patio towards the house.

Photograph by Molly Adams.

|

The moment I came across images of an unidentified house and garden while perusing the Maida Babson Adams Collection at the Archives of American Gardens, I knew I had to find out more about the cozy, modern home. Perhaps it was the way Molly (Maida Babson) Adams had photographed the home to emphasize the contrast between the horizontal lines of the house and the organic shapes of the garden, or perhaps it was the inviting butterfly chairs on the patio, but I was intrigued. Nothing was written on the back of the photograph except “Gleason.” The only revealing cataloging information was that the garden was designed by landscape architect Nelva Weber; it was anonymously featured in her 1976 book How to Plan Your Own Home Landscape. I continued to wonder about the house. Who lived there? What was their idea of home?

Over the next few months I spent a few minutes each day searching for the house. Molly Adams was a prolific garden photographer, shooting gardens in the Northeast from the 1960s through the 1980s for magazines such as Flower Grower and Popular Gardening & Living Outdoors. Flipping through my mental rolodex of mid-century architects, my first thought was that the home may have been designed by Joseph Eichler or Carl Koch, both prolific mid-century architects who designed small, modern homes for suburban families. Geographically it seemed most likely that the house was located in Massachusetts, New Jersey, or Connecticut. That meant Eichler, builder of mass-produced homes in California, was out. In the beginning I spent an embarrassing amount of time Googling “Molly Adams Gleason,” “Gleason modern house,” Gleason modern garden,” “Gleason Connecticut modern,” “Nelva Weber modern,” etc. Clearly, this was going to be a long search.

Back to the drawing board, and failed by modern tools, I turned to books. Home design books and traveling museum shows like the Museum of Modern Art’s “Good Design” exhibits were key to disseminating new ideas about suburban living to a design-conscious middle-class. I checked out a multitude of 1950s home design books from the library, including John Hancock Callender’s 1953 book Before You Buy a House. The book was of interest to me because it included a house by Hugh Stubbins, who was on my list of potential architects. And there it was, staring right back at me on page 113. The house was not designed by Hugh Stubbins, but by the architectural firm Nemeny & Geller. Designed for a rolling, wooded site in Morristown, New Jersey, the house in the book was part of the then-new Robert Morris Park development.

Nemeny & Geller created a basic house plan to be used throughout the development that could be varied through the addition of a garage or different paint colors, yet still present a unified front. A garden design by Nelva Weber surely further distinguished the Gleason house from the rows of similar houses in the neighborhood. Robert Morris Park was a stepping stone between owning one of the “little boxes made of ticky tacky” (from the 1962 Malvina Reynolds song) and paying a well-known architect to build a custom home. Originally 305 houses were planned, but only a small percentage of them were ever built. A quick Google search confirmed that there was a Gleason living in Morristown, and a Google street view search revealed the house itself. It took hours of searching for the right book to divulge the identity of the garden, but only minutes on the internet to confirm its identity.

As with most archives, a number of images in the Archives of American Gardens came to the archives without documentation. The research efforts of museum specialists and volunteers have saved many gardens in the collection from anonymity. Are you interested in digging into a garden mystery? Learn more about AAG’s Mystery Gardens Initiative and how you can contribute to preserving America’s garden heritage.

-Kate Fox

Kate Fox is a guest blogger who is currently working on an upcoming SITES exhibition for the Archives of American Gardens at Smithsonian Gardens

Labels:

Archives,

Gardens,

Libraries,

Photographs

Friday, January 20, 2012

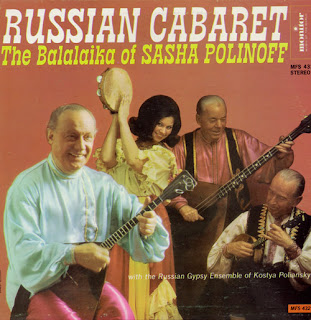

Come in from the Cold: Warming up with Monitor Records

If you were to wander into the dimly lit Russian cafe in lower Manhattan called the Two Guitars on almost any evening you would find Sasha Polinoff entertaining the guests...Sasha sets the Slavic mood for the vodka, caviar, and the Kiev cutlets. (MFS 432)

Monitor Records, founded in 1956 by Michael Stillman and Rose Rubin in New York City, issued over 250 recordings of music from around the world. An artifact of the period's interest in "exotic" records, the recordings were appealing to people for the same reason I find them fascinating today: they project a sense of another place. Sometimes these places aren't "real"--much of the music on Monitor was licensed from state-sponsored record labels in the then-Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Sometimes they are--as is the case for the recordings made in venues in New York City. But from the covers to the liner notes to the music itself, the albums are transporting.

The Monitor albums I'm feeling drawn to these days all mention cafes and nightlife and warmth, and make me want to bundle up and find a little place where the food is filling, the drinks flowing, and the music wistful (wistful for what? I'm not sure, but when music makes you feel like you're somewhere else, it kind of feels like that place is lost to you at the same time). If you feel like that too, here are my picks for getting cafe-cozy, accompanied by excerpts from the liner notes.

The Feenjon Group

Belly Dancing at the Cafe Feenjon, (MFS 497)

Liane

Vienna by Night (MP 510)

Bela Babai and his Fiery Gypsies

An Evening at the Chardas (MFS 700)

"Bela Babai...can be heard nightly at New Yorks Chardas where lovers of Gypsy music and fine Hungarian cuisine meet. Wherever Bela Babai appears the musical greats come to hear..."

-Cecilia Peterson, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

Friday, January 13, 2012

The Donald A. Cadzow Photograph Collection

The Donald A. Cadzow photograph collection documents numerous indigenous cultures across North America, Canada, and Alaska through the various expeditions and archeological excavations he conducted for the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation from 1916 until 1927.

The son of Hugh and Nellie Cadzow, Donald was born in Auburn, New York in 1894. In 1911, at the age of 17, he traveled to the far Canadian Northwest to live with his uncle Daniel Cadzow at the Rampart House, a Hudson Bay Company trading post on the Alaska-Yukon boundary line. After five years there, Cadzow returned to the United States. He began working for George Gustav Heye in the fall of 1916, but enlisted as seaman in the U.S.N.R.F. on January 20, 1918, only to be released from service on December 22 that same year. He returned to work for Heye at the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation on January 1, 1919, and worked there until 1928.

Between 1917 and 1919, Cadzow, collected artifacts and archaeological materials from the Copper and Kogmollok Eskimo, the Loucheux, Slavey, and Woodland Cree of Alberta, Canada. In 1919, Cadzow assisted Alanson Skinner on an archeological excavation in Cayuga County, New York. Cadzow next worked with Mark Harrington: excavating a site on Staten Island, New York in 1920; on the Hawikku expedition to study Zuni Indian culture in McKinley County, New Mexico in 1921; and to Arkansas and Missouri in 1922. In 1924 and 1925 he conducted an expedition to a prehistoric Algonkian burial site on Frontenac Island, Cayuga Lake, in New York; traveled to the Bungi tribe in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and the Prairie Cree in Saskatchewan, Canada. He continued this work in 1926 again visiting the Prairie Cree and also the Bush Cree in Saskatchewan, the Assiniboin in Saskatchewan and Alberta; the Iroquois and the Northern Piegan (Blackfoot) in Alberta. In 1927, the last year that Cadzow worked for Heye, he assisted George P. Putnam on an expedition to Baffin Island and the Hudson Bay district to visit the Sikosuilarmiut, Akuliarmiut, and Quaumauangmiut Eskimos.

After his work at MAI, in 1928 he took a job in the Bond Department of Lage & Co., a brokerage company in New York City. He was later state archeologist for the Pennsylvania Historical Commission from ca. 1929-39; and executive secretary from 1939-45. He was also treasurer of the Eastern States Archeological Federation from 1940-42. In 1945 he was named executive director of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and held the position until 1956. He died on February 9, 1960, in Pennsylvania. During his career Cadzow gave a number of lectures and radio talk programs, and published extensively in Indian Notes (a publication of Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation), for the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, in a variety of publications, and several books.

See more of Cadzow's photographs, as well as objects he collected for the museum here.

~Jennifer R. O'Neal, Head Archivist, NMAI Archive Center

|

| Kainah (Blood) man, 1882 (P01531) |

The son of Hugh and Nellie Cadzow, Donald was born in Auburn, New York in 1894. In 1911, at the age of 17, he traveled to the far Canadian Northwest to live with his uncle Daniel Cadzow at the Rampart House, a Hudson Bay Company trading post on the Alaska-Yukon boundary line. After five years there, Cadzow returned to the United States. He began working for George Gustav Heye in the fall of 1916, but enlisted as seaman in the U.S.N.R.F. on January 20, 1918, only to be released from service on December 22 that same year. He returned to work for Heye at the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation on January 1, 1919, and worked there until 1928.

|

| Young Assiniboin (Stoney) woman, 1926 (N11750) |

Between 1917 and 1919, Cadzow, collected artifacts and archaeological materials from the Copper and Kogmollok Eskimo, the Loucheux, Slavey, and Woodland Cree of Alberta, Canada. In 1919, Cadzow assisted Alanson Skinner on an archeological excavation in Cayuga County, New York. Cadzow next worked with Mark Harrington: excavating a site on Staten Island, New York in 1920; on the Hawikku expedition to study Zuni Indian culture in McKinley County, New Mexico in 1921; and to Arkansas and Missouri in 1922. In 1924 and 1925 he conducted an expedition to a prehistoric Algonkian burial site on Frontenac Island, Cayuga Lake, in New York; traveled to the Bungi tribe in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and the Prairie Cree in Saskatchewan, Canada. He continued this work in 1926 again visiting the Prairie Cree and also the Bush Cree in Saskatchewan, the Assiniboin in Saskatchewan and Alberta; the Iroquois and the Northern Piegan (Blackfoot) in Alberta. In 1927, the last year that Cadzow worked for Heye, he assisted George P. Putnam on an expedition to Baffin Island and the Hudson Bay district to visit the Sikosuilarmiut, Akuliarmiut, and Quaumauangmiut Eskimos.

|

| Pokiak (Inuvialuit Inupiaq), 1917-1919 (N02023) |

See more of Cadzow's photographs, as well as objects he collected for the museum here.

~Jennifer R. O'Neal, Head Archivist, NMAI Archive Center

Labels:

American Indian,

Archives,

Collection Spotlight,

Photographs

Indentures of Apprenticeship from Early Nineteenth Century New York City

The Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology in Washington, D.C. has a manuscripts collection with an amazing variety of documents. One box from the collection contains over 140 contracts of indenture (partially printed, and partially handwritten) from the Commissioners of the Alms-House and Bridewell, New York City, created between the years 1821 and 1823. These contracts record the apprenticeships of poor and abandoned children who were assigned to learn various trades under the supervision of established business owners. In return for room and board and a basic education, the indentured workers were supposed to provide several years of labor for their employers before being released from their contracts. Providing a grim window into both the diversity of trades and the depths of poverty in the growing city of New York, these indentures were a pragmatic measure taken by the government for the support of children who lacked parents or guardians. Here are two examples of these historic documents.

The first indenture, shown to the left, is for 14-year-old Henry Valentine, apprenticed to John Cochran, a "Mahogany Chair and Sopha [i.e. Sofa] Maker."

The second indenture, seen below, is for 14-year-old Clark Martin, apprenticed to John H. Metzler, a shoemaker. Both indentures are signed by the apprentice, the tradesman to whom the boy was assigned, and the government agent (John Hunter) who drew up the contract.

At the end of the indenture period, each boy was to be released from his apprenticeship with "a new suit of clothing in addition to his old, and a new Bible." And, if all went well, the young men would be able to go forth and establish their own businesses, benefitting from the hard years in service that they spent learning their trades. But not all situations necessarily turned out as planned; the contracts could be cancelled for a variety of reasons. The contract for Clark Martin, above, has a note written along the left side of the page that the agreement was "cancelled by consent of justice, Decem. 24th, 1825," with no further details.

More information on contracts of indenture from the city of New York can be found on the New-York Historical Society website, where a larger collection of these contracts is located.

New York (N.Y.). Alms-House and Bridewell Commission. Indentures of Apprenticeship, 1821-1823. Call number: MSS 001624 B SCDIRB Dibner Library

--Diane Shaw, Special Collections Cataloger, Smithsonian Institution Libraries

The first indenture, shown to the left, is for 14-year-old Henry Valentine, apprenticed to John Cochran, a "Mahogany Chair and Sopha [i.e. Sofa] Maker."

At the end of the indenture period, each boy was to be released from his apprenticeship with "a new suit of clothing in addition to his old, and a new Bible." And, if all went well, the young men would be able to go forth and establish their own businesses, benefitting from the hard years in service that they spent learning their trades. But not all situations necessarily turned out as planned; the contracts could be cancelled for a variety of reasons. The contract for Clark Martin, above, has a note written along the left side of the page that the agreement was "cancelled by consent of justice, Decem. 24th, 1825," with no further details.

More information on contracts of indenture from the city of New York can be found on the New-York Historical Society website, where a larger collection of these contracts is located.

New York (N.Y.). Alms-House and Bridewell Commission. Indentures of Apprenticeship, 1821-1823. Call number: MSS 001624 B SCDIRB Dibner Library

--Diane Shaw, Special Collections Cataloger, Smithsonian Institution Libraries

Labels:

Archives,

History and Culture,

Libraries

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

Sydel Silverman: Preserving the Anthropological Record

The National Anthropological Archives recently acquired the papers of Sydel Silverman, an anthropologist known for her work as a researcher, writer, academic administrator, and foundation executive. After receiving her PhD from Columbia University in 1963, she taught at Queens College in New York (1962-75) and became Executive Officer of the CUNY PhD Program in Anthropology (1975-86). She later served as president of the Wenner-Gren Foundation from 1987-1999.

While at the Wenner-Gren Foundation, Silverman’s interest in the history of anthropology led her to become heavily involved in an effort to preserve anthropological records. In 1991, along with Dr. Nancy Parezo, she began planning a conference that would deal with the preservation of anthropology’s historical record. The conference, called "Preserving the Anthropological Record: Issues and Strategies," was held in spring 1992. Anthropologists, archaeologists, archivists, librarians, museum specialists, and potential funders met to identify the issues associated with preserving anthropological records. The conference attendees discussed the issues of records creation and use, ethical concerns, and the necessity of educating stakeholders.

In "Preserving the Anthropological Record," an article written about the conference for the February 1993 issue of Current Anthropology, Silverman described the Resolution on Preserving Anthropological Records that the conference adopted. The Resolution stated that "anthropologists have a professional responsibility to serve as stewards" of their "unpublished anthropological materials" because they are "irreplaceable" and "unique resources" that are "essential for future research and education." Anthropological records contain cultural information that is valuable to many different parties: the anthropologist who gathered the data, the informants who supplied the anthropologist with that data, other members of the informants’ community, or those who wish to study that community.

Papers from the conference were published in a volume entitled Preserving the Anthropological Record, co-edited by Silverman and Parezo. This publication described why anthropological records should be kept, the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders, preservation issues, guidelines and strategies. In the book’s Introduction, Silverman expressed the core concern of the conference members: "For anthropology, the unpublished records of the past are of more than historical interest…They constitute the primary data of all research—data that are unique and unrecoverable." Silverman and the rest of the conference participants recognized that much of the anthropological record consisted of grey literature—field notes, interviews, data sets, and more—that could be of great value to future researchers.

In May 1993, a second Wenner-Gren conference, "Preserving the Anthropological Record II: Toward a Disciplinary Center," was held to define an action plan. This conference led to the creation of CoPAR, the Council for the Preservation of Anthropological Records. According to the statement on its homepage, CoPAR "sponsors programs that foster awareness of the importance of preserving anthropological records; provides consulting and technical support to archival repositories; provides information on records location and access; and fosters collaboration between archivists responsible for anthropological collections and tribal archivists." For more information on CoPAR, and Sydel Silverman’s involvement in the movement to preserve anthropological records, visit the National Anthropological Archives website http://www.nmnh.si.edu/naa/.

Christy Fic, Contract Processing Archivist

National Anthropological Archives

While at the Wenner-Gren Foundation, Silverman’s interest in the history of anthropology led her to become heavily involved in an effort to preserve anthropological records. In 1991, along with Dr. Nancy Parezo, she began planning a conference that would deal with the preservation of anthropology’s historical record. The conference, called "Preserving the Anthropological Record: Issues and Strategies," was held in spring 1992. Anthropologists, archaeologists, archivists, librarians, museum specialists, and potential funders met to identify the issues associated with preserving anthropological records. The conference attendees discussed the issues of records creation and use, ethical concerns, and the necessity of educating stakeholders.

In "Preserving the Anthropological Record," an article written about the conference for the February 1993 issue of Current Anthropology, Silverman described the Resolution on Preserving Anthropological Records that the conference adopted. The Resolution stated that "anthropologists have a professional responsibility to serve as stewards" of their "unpublished anthropological materials" because they are "irreplaceable" and "unique resources" that are "essential for future research and education." Anthropological records contain cultural information that is valuable to many different parties: the anthropologist who gathered the data, the informants who supplied the anthropologist with that data, other members of the informants’ community, or those who wish to study that community.

|

| Silverman Papers, Box 16, folder "Siena Notebooks [4 of 5]" Silverman unpublished notebook, cover |

|

| Notes on Palio of Siena (a festival) Siena, Italy, 1980 |

In May 1993, a second Wenner-Gren conference, "Preserving the Anthropological Record II: Toward a Disciplinary Center," was held to define an action plan. This conference led to the creation of CoPAR, the Council for the Preservation of Anthropological Records. According to the statement on its homepage, CoPAR "sponsors programs that foster awareness of the importance of preserving anthropological records; provides consulting and technical support to archival repositories; provides information on records location and access; and fosters collaboration between archivists responsible for anthropological collections and tribal archivists." For more information on CoPAR, and Sydel Silverman’s involvement in the movement to preserve anthropological records, visit the National Anthropological Archives website http://www.nmnh.si.edu/naa/.

|

| Sydel Silver Papers, Box 29, folder "April 1995, Reno, NV COPAR" Silverman is third from right in the front row |

Christy Fic, Contract Processing Archivist

National Anthropological Archives

Labels:

Anthropologists,

Archives,

Preservation

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

RESEARCHER FINDS PAIN AND RELIEF IN THE ARCHIVES CENTER

The Sterling Drug Company papers are held at the Smithsonian’s off-site facility, which turns out to be a great thing: you get to go right into the “stacks” because there’s no public reading room, and that means walking by noncommissioned items from the Museum of Natural History—it seemed like every time I went I noticed a new rhinoceros or whale peeking out from behind a tarpaulin. I felt a little guilty because one of the archivists had to commute out to the facility every day and work at a makeshift table in the stacks next to me, but she was cheerful good company and kept insisting that she didn’t mind.

| Talwin advertisement, 1965 |

Sterling, a voracious grow-through-acquisitions drug company, ended up selling some of the early 20th century’s most important medicines: aspirin; the sulfa drugs; neosalvarsan (the famed “magic bullet” for syphilis); the first barbiturate sedatives Veronal and Luminal; the first synthetic narcotic Demerol; and many more. The most significant of these drugs came into Sterling’s possession during the World Wars, when the U.S. government confiscated the patents and sometimes even factories of German pharmaceutical houses and gave or auctioned them off to American companies.

| Talwin advertisement, 1969 |

One particularly fascinating drug saga I tracked through the archive was the rise and fall of a narcotic (pain reliever) named Talwin. Talwin debuted with much ballyhoo in 1967 as the first non-addictive narcotic—a holy grail of sorts for pharmaceuticals, and a discovery preceded by decades of dashed dreams. Sterling’s ads weren’t shy about the new miracle drug, as these examples show; note how they remind readers, repeatedly, that the drug requires no special narcotics licenses or prescription triplicates. Eventually, however, the occasional instances of abuse, dependence, and addiction grew into a genuine public health problem in Chicago and a few other cities by the late 1970s. Turned out that the drug by itself was barely addictive, but, if crushed up with a common antihistamine (Pyribenzamine) and injected, it was a passable substitute for heroin—something addicts were much desirous of in the late 1970s when heroin prices had risen. Eventually Talwin was put on the Schedule of Controlled Substances after all. (For more details on the Talwin story, see http://pointsadhsblog.wordpress.com/2011/11/21/forgotten-drugs-of-abuse-part-1-ts-and-blues/)

| Talwin advertisement, 1969 |

| Talwin advertisement, 1972 |

The Sterling collection has plenty of interesting material, all of which is closely and, for the most part, accurately described in a 400+ page finding aid. Record Group 1, which I only peeked at, contains actual samples of Sterling Drug packaging, labels, products, &etc. I spent most of my time in Record Groups 2 and 3, which contain marketing materials: medical journal advertisements (of course), and a wide range of mailings to physicians, from research-heavy booklets to lighthearted Madison Avenue gimmickry.

Record Group 4 includes material about the company, and there’s a little something for everyone: for business historians there are many, many in-house newsletters from various aspects of the company (the factory, the sales force, etc.), which detail company life and corporate culture over the century. The annual reports to stock holders give a financial overview. Clipping files collect news coverage of the company. Unfortunately there is nothing on corporate decision making, policy discussions, and the like.

Overall, however, there is much here of value to historians of pharmaceuticals, of the pharmaceutical industry, and of advertising.

David HerzbergAssociate ProfessorHistory Department546 Park HallUniversity at Buffalo (SUNY)Buffalo, NY 14260http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~herzberg

Blog editor's note: We're very pleased to present this unsolicited report from Prof. Herzberg. The "cheerful" archivist mentioned in his first paragraph was an Archives Center stalwart, Cathy Keen.

Tuesday, January 3, 2012

Freer for All

|

| Charles Lang Freer, c. 1916 Smithsonian Institution Archives |

Today, January 3, marks the 106th anniversary of Charles Lang Freer tremendous gift to the American public. On this day in 1905, Freer, a wealthy railroad car manufacturer, offered to donate his vast art collection of artworks from American, Chinese, Japanese, Indian and Near East artists to the Smithsonian. Freer’s collection consisted of over 2,250 objects, including James McNeill Whistler’s Peacock Room. In addition to his collections, Freer also offered $500,000 to build a museum to house the art and an endowment to care for works.

Though the Smithsonian was initially reluctant to agree to Freer’s gift, with help from President Theodore Roosevelt, the Smithsonian Board of Regents and US Congress formally accepted Freer’s gift on May 5, 1906. Freer’s main motive for sharing his collection was to make it available for the public and for scholars. As such, Freer’s will stated that only objects in his personal permanent collection could be exhibited in the Freer Gallery and that pieces of his collection could not be displayed elsewhere.

Though the Smithsonian was initially reluctant to agree to Freer’s gift, with help from President Theodore Roosevelt, the Smithsonian Board of Regents and US Congress formally accepted Freer’s gift on May 5, 1906. Freer’s main motive for sharing his collection was to make it available for the public and for scholars. As such, Freer’s will stated that only objects in his personal permanent collection could be exhibited in the Freer Gallery and that pieces of his collection could not be displayed elsewhere.

|

| Whistler's Peacock Room, c. 1930 Smithsonian Institution Archives |

The Freer Gallery of Art opened May 2, 1923. Within its first month of operation 32, 648 people visited the new museum. Freer’s vision of sharing his collections with the public has grown into reality over the years. The Gallery’s wonderful exhibits and website have broadened access to the museum’s collections. Additionally, the Smithsonian’s Collection Search Center connects collections across the Institution, allowing visitors to research about Freer and his artworks in more inclusive forum.

Courtney Esposito, Institutional History Division, Smithsonian Institution Archives

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)