Unlike many of the tribes discussed in the People of India, the Bhurs, at least in the context in which they are discussed by the British, seem to have all but disappeared from India. However, before their diaspora, they were one of the most long settled tribes on the subcontinent. In fact, the British surmised that, in all likelihood, the Bhurs were an aboriginal tribe. They founded the town of Baraitch, and had significant influence in central Oude for quite some time. Their time in the sun came to an abrupt end when they were scattered by the then Emperor of the Delhi Sultanate. POI identifies their conqueror as “Alla-hoo-deen Ghazee of Delhi”, and remarks that the Bhurs “appear to have been systematically extirpated by Mahomedon conquerors in the early part of the 14th century.” Their last stand before submission appears to have been at the Sultanpur (a name given by Muslim conquerors. The original Bhur designation has been lost) fort town, where Ghazee laid siege to them. They put up strong resistance at first, but, according to historians, were defeated during the Holi festival, as a result of excessive drinking and festivities, and the inevitable carelessness that ensues. After this defeat, Baraitch was more or less deserted, and fell into dereliction. The following decades saw a similar scattering of the tribe all throughout Oude, until, by the time of POI’s publication, the region was something of an unmarked graveyard. “Brick ruins of forts, houses, and wells” filled the countryside, but none of the current inhabitants seemed to have any knowledge of their unfortunate predecessors. Those who managed to remain were forced to accept menial positions, and occupied a very low echelon in society. The Bhurs, and their devastating fall, are yet another example of India’s endless cultural, political, and religious revolutions; its constant, all encompassing samsara.

Monday, November 28, 2011

The People of India - The Bhurs

The People of India series was researched and written by School Without Walls student, Cal Berer. Cal was an intern at the Freer|Sackler Archives from January 2011-June 20011 where he was then sponsored by the State Department to learn Hindi while spending the summer in India.

The Bhurs

Unlike many of the tribes discussed in the People of India, the Bhurs, at least in the context in which they are discussed by the British, seem to have all but disappeared from India. However, before their diaspora, they were one of the most long settled tribes on the subcontinent. In fact, the British surmised that, in all likelihood, the Bhurs were an aboriginal tribe. They founded the town of Baraitch, and had significant influence in central Oude for quite some time. Their time in the sun came to an abrupt end when they were scattered by the then Emperor of the Delhi Sultanate. POI identifies their conqueror as “Alla-hoo-deen Ghazee of Delhi”, and remarks that the Bhurs “appear to have been systematically extirpated by Mahomedon conquerors in the early part of the 14th century.” Their last stand before submission appears to have been at the Sultanpur (a name given by Muslim conquerors. The original Bhur designation has been lost) fort town, where Ghazee laid siege to them. They put up strong resistance at first, but, according to historians, were defeated during the Holi festival, as a result of excessive drinking and festivities, and the inevitable carelessness that ensues. After this defeat, Baraitch was more or less deserted, and fell into dereliction. The following decades saw a similar scattering of the tribe all throughout Oude, until, by the time of POI’s publication, the region was something of an unmarked graveyard. “Brick ruins of forts, houses, and wells” filled the countryside, but none of the current inhabitants seemed to have any knowledge of their unfortunate predecessors. Those who managed to remain were forced to accept menial positions, and occupied a very low echelon in society. The Bhurs, and their devastating fall, are yet another example of India’s endless cultural, political, and religious revolutions; its constant, all encompassing samsara.

Unlike many of the tribes discussed in the People of India, the Bhurs, at least in the context in which they are discussed by the British, seem to have all but disappeared from India. However, before their diaspora, they were one of the most long settled tribes on the subcontinent. In fact, the British surmised that, in all likelihood, the Bhurs were an aboriginal tribe. They founded the town of Baraitch, and had significant influence in central Oude for quite some time. Their time in the sun came to an abrupt end when they were scattered by the then Emperor of the Delhi Sultanate. POI identifies their conqueror as “Alla-hoo-deen Ghazee of Delhi”, and remarks that the Bhurs “appear to have been systematically extirpated by Mahomedon conquerors in the early part of the 14th century.” Their last stand before submission appears to have been at the Sultanpur (a name given by Muslim conquerors. The original Bhur designation has been lost) fort town, where Ghazee laid siege to them. They put up strong resistance at first, but, according to historians, were defeated during the Holi festival, as a result of excessive drinking and festivities, and the inevitable carelessness that ensues. After this defeat, Baraitch was more or less deserted, and fell into dereliction. The following decades saw a similar scattering of the tribe all throughout Oude, until, by the time of POI’s publication, the region was something of an unmarked graveyard. “Brick ruins of forts, houses, and wells” filled the countryside, but none of the current inhabitants seemed to have any knowledge of their unfortunate predecessors. Those who managed to remain were forced to accept menial positions, and occupied a very low echelon in society. The Bhurs, and their devastating fall, are yet another example of India’s endless cultural, political, and religious revolutions; its constant, all encompassing samsara.

To see all text and images of the Bhurs as they are represented in the People of India, go to our catalog in the Collections Search Center.

The People of India series will be published once a month highlighting the various tribes as they're covered in the People of India.

Cal Berer, Intern

Labels:

Anthropologists,

Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives,

History and Culture,

Photographs,

The People of India Series

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

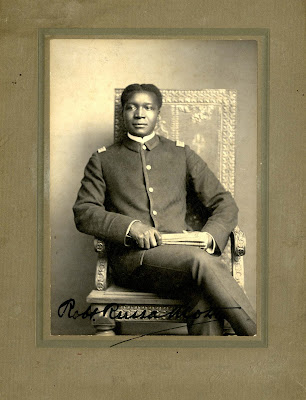

Image of the Day: Robert R. Moton

Robert Russa Moton (1867 – 1940) was an educator and the second president of Tuskegee Institute, perhaps lesser known in comparison to the school’s founder and first principal, Booker T. Washington, or the Institute’s third president, Frederick Douglass Patterson. However, Dr. Moton, as did his predecessor, dedicated his life to educating African Americans and shared Washington’s philosophy towards industrial education as a means of advancement for the recently emancipated population.

Dr. Moton, the great-great-great-grandson of an “African slave merchant”, who after selling his fellow countrymen to slavers found himself on a ship chained to an African he recently sold to slave traders. The merchant was purchased and taken to Amelia County, Virginia, by a tobacco planter, where some hundred years later his descendant Robert Russa Moton was born on August 26, 1867. Dr. Moton recounts this story and the events that shaped his life in his1920 autobiography, Finding a Way Out.

A graduate of Hampton Institute, Moton also taught at the school and was the administrator for the Native American students attending the Institute. He later served for twenty-five years as Commandant of Cadets, overseeing the discipline of all the students. In 1915, Moton was appointed principal of Tuskegee Institute after the death of Booker T. Washington. To the trustees of Tuskegee, Moton’s ability to get along with both black and white southerners and his potential to solicit funding support from northern philanthropists made him the perfect candidate to further the work of Washington.

Moton served as principal of Tuskegee for twenty years. Under his administration, Tuskegee expanded its academic program, added more buildings for the Institute to carry out its training, and strengthen the school’s reputation. Dr. Moton retired in 1935 and died in 1940.

Jennifer Morris

Archivist

Anacostia Community Museum Archives

Dr. Moton, the great-great-great-grandson of an “African slave merchant”, who after selling his fellow countrymen to slavers found himself on a ship chained to an African he recently sold to slave traders. The merchant was purchased and taken to Amelia County, Virginia, by a tobacco planter, where some hundred years later his descendant Robert Russa Moton was born on August 26, 1867. Dr. Moton recounts this story and the events that shaped his life in his1920 autobiography, Finding a Way Out.

A graduate of Hampton Institute, Moton also taught at the school and was the administrator for the Native American students attending the Institute. He later served for twenty-five years as Commandant of Cadets, overseeing the discipline of all the students. In 1915, Moton was appointed principal of Tuskegee Institute after the death of Booker T. Washington. To the trustees of Tuskegee, Moton’s ability to get along with both black and white southerners and his potential to solicit funding support from northern philanthropists made him the perfect candidate to further the work of Washington.

Moton served as principal of Tuskegee for twenty years. Under his administration, Tuskegee expanded its academic program, added more buildings for the Institute to carry out its training, and strengthen the school’s reputation. Dr. Moton retired in 1935 and died in 1940.

Jennifer Morris

Archivist

Anacostia Community Museum Archives

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

The Art and Craft of Green Gables: A California Estate

The Arts and Crafts movement gained momentum in Britain during the 1880s and was focused on uniting the natural landscape to architecture, the garden, and the home. Those at the forefront of the movement in England included architect Philip Webb (1831-1915) who was commissioned by the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement William Morris (1834-1896) to design Red House and its surrounding gardens in 1859. Red House became one of the most influential designs in the Arts and Crafts movement because of its incorporation of nature into daily life.

In America, Arts and Crafts gardens were marked by their regional diversity and use of native species and locally historic styles, which created a national Arts and Crafts style much less cohesive than its British counterpart. Seamless transitions between the design of homes and gardens in America grew from the practice of well-known Arts and Crafts architects like Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) who popularly fused architectural and garden principles in houses like his Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania.

On the West Coast, the Arts and Crafts movement took the form of the California Mission Revival style and the bungalow style of architecture that brothers Charles (1868-1957) and Henry Greene (1870-1954), also known as Greene & Greene, popularized through their designs. Charles Greene’s commission in the early twentieth century for Mortimer and Bella Fleishhacker to create a seventy-five acre garden called Green Gables in Woodside, California, is one of the largest gardens created by an Arts and Crafts designer. While Green Gables features strong European influences, including an Italianate arcade and design, Greene’s composition remains true to the Arts and Crafts sensibilities of native plantings, regional style, and natural, organic designs. In addition to designing the gardens, exterior walkways and pools over the course of twenty years, Greene also personally designed tables, chairs, and doors for the house.

For more information about Arts and Crafts gardens, see Wendy Hitchmough, Arts and Crafts Gardens (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1998)

For more information about Arts and Crafts gardens, see Wendy Hitchmough, Arts and Crafts Gardens (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1998)

Find out more information about the Garden Club of America Collection at the Archives of American Gardens.

Lucy Shirley, 2011 Katzenberger Art History Intern

Archives of American Gardens

Smithsonian Gardens

Smithsonian Gardens

Monday, November 21, 2011

Radio Days: Moe Asch Before Folkways

|

| Radio Laboratories business card |

As someone who has been up to the

elbows in Asch material for almost three months, I’m not ashamed to admit that

I have a favorite part of the collection. But it isn’t the Production Files

series with its beautiful artwork, or even the Correspondence series with its

letters from artists, managers, and fans from all over the world. No, my

favorite part is the early Biographical series, which chronicles the personal

and pre-Folkways life of Moe Asch. Though it can be overshadowed by the

accomplishments of his later years, the story of Moe Asch the young radio

pioneer is one that deserves to be told as well. Before Folkways, Moe Asch was

bringing sound to the masses in a different way, over P.A. systems and radio

sets. The documents and other materials found in the Asch Biographical series

give insight into the nascent field of radio technology, life in Depression-era

New York City, and the early career of the man who would be Moe.

Before

he was recording the world of sound, Moe Asch was immersed in the world of

radio electronics. He worked as lab

engineer in charge of repairs at Walthal’s Electric Company in Manhattan for

five years. During and after his time

there, Moe was an avid scholar and innovator in the field of electronic

science. In 1929, he documented “equipment for aerial installation” that he

himself had invented; three years later he wrote to a potential client as an

inventor offering his product for sale. He also submitted articles on equipment

and technique to trade publications like Radio

Engineering and Radio Retailing

in the early ‘30s.

Letter to Virgil Graham from Moses Asch, regarding radio receivers in automobiles, undated

Moe became known throughout the community as a skilled radio man who was up-to-date with the latest technology, a reputation that led to some surprising interactions. In an undated letter from the 1930s, he warns a colleague about those who might want to exploit his knowledge for nefarious purposes: “… the police department in New York officially opened its Police Radio network, and I’ve been approached by bootleggers and (so called) gangsters to install radio receivers in their automobiles for reception of these signals.”

Throughout

the Great Depression, Moe remained active in the field, attending conferences

and joining several professional organizations. He was a member of the

Institute of Radio Engineers and the United Electrical and Radio Workers of the

World, and became secretary of the Brooklyn chapter of the Institute of Radio

Service Men. In 1936, he served as the chairman of the Standards Committee and

the head of the Educational Committee for the International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers.

It was during this time that Moe

and his partner, Harry Mearns, started their own business that focused on radio and

public address system repair, rentals, and installation. Radio Laboratories did

business with individuals, theaters, professional organizations, and political

groups all over New York City as well as in neighboring states. Although the partnership ended in 1940, the

electronics expertise and client contacts Moe gained during the Radio Labs

years would serve him well when he entered the realm of commercial recording.

The Biographical series of the Moses and Frances Asch Collection provides a glimpse into an era of exciting technological innovations and the life of an enterprising young businessman in the midst of a tumultuous period in American history. For this and other reasons (who can resist the charm of vintage ads singing the praises of newly-minted FM radio?), this series ranks as one of the most fascinating parts of the Archives. Anyone looking to examine the life of Moe Asch before Folkways would do well to start here.

- Aja Bain, Intern, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Television Art

Next week is Thanksgiving, but on Monday, November 21 we give thanks to the TV! The United Nations declared World Television Day back in 1996. Since I’m at work and I don’t have a TV on hand to celebrate, I thought I’d share some artwork symbolizing this communication technology.

| Sculptor Friedlander standing on the unfinished RCA building marquee under his Television relief sculptures, ca. 1934 |

In this Peter A. Juley & Son photo, sculptor Leo Friedlander (1890-1966) stands with a boy on the unfinished iconic marquee of the RCA Building (now GE Building) at Rockefeller Center in New York City. Above them at 15 ft. tall and 10 ft. wide are Friedlander’s Television sculpture reliefs. The group on the left, called Production, depict a female figure dancing while another figure films her movement. On the right side of the marquee, Reception receives this transmission of the dancing girl and displays it in her hands for the audience (or viewers) represented by mother and child figures.

| Leo Friedlander standing in front of a scale model of Television |

Check out other television related items through the Smithsonian Collections Search. Have a good World Television Day!

Emily Moazami, Photograph Archivist, Research & Scholars Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Labels:

Archives,

Artists,

Arts and Design,

Collection Spotlight,

Outdoor Sculpture,

Photographs,

Works of Art

Monday, November 7, 2011

Turkeys, Fort Marion, and Making Medicine

Images of turkeys can be found in artwork at the National Anthropological Archives. One type of art in the NAA's collection containing turkeys are drawings that were created by American Indian prisoners at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, such as this graphite and colored pencil drawing depicting a turkey hunt by an anonymous Cheyenne artist.

The above illustration was part of a book of drawings transferred to the U.S. National Museum (Smithsonian) in 1877 by the U.S. War Department that had collected it in 1875 from an unidentified Cheyenne prisoner at Fort Marion. This was the original War Department label for the book.

Click here to see the complete set of drawings contained in the 1875 anonymous Cheyenne drawing book (MS 39A) in the National Anthropological Archives.

In 1875, following the Southern Plains Indian war, 72 Native Americans, primarily Kiowas, Cheyennes and Araphoes, were captured by the U.S. Army and imprisoned and held hostage to ensure the peaceful conduct of their tribes.

| Stereograph of "Indians at Fort Marion" Photo Lot 90-1, number 336, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution |

| "Captain Pratt and Indian boys posed in front of building, Fort Marion, Florida, 1878" Negative 54546, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. |

| Stereograph of Indian prisoners at Fort Marion posing with visitors Photo Lot 90-1, number 334, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution |

One of the prisoner artists at Fort Marion was Making Medicine (later known as David Pendleton Oakerhater), a warrior and leader amongst the Cheyenne Tribe of Oklahoma.

In 1923 the Bureau of American Ethnology, whose collection later became part of the National Anthropological Archives, received a donation of one of Making Medicine's Fort Marion sketchbooks (MS 39B), seen here.

The donor's brother had been given the sketchbook by his cousin, George Fox, who worked as an interpreter at Fort Marion between1875 to 1878. This is the donor's description of how she acquired the drawing book.

Making Medicine's sketchbook depicts his experiences as a prisoner at Fort Marion, including participating in drills with fellow prisoners, being photographed and giving archery lessons to ladies.

Making Medicine also created scenes of life before prison, including village life and hunting scenes, which of course included turkeys.

|

| Making Medicine or David Pendleton Oakerhater, May 1881 Photo courtesy of Oklahoma State University Library |

The donor's brother had been given the sketchbook by his cousin, George Fox, who worked as an interpreter at Fort Marion between1875 to 1878. This is the donor's description of how she acquired the drawing book.

Making Medicine's sketchbook depicts his experiences as a prisoner at Fort Marion, including participating in drills with fellow prisoners, being photographed and giving archery lessons to ladies.

Making Medicine also created scenes of life before prison, including village life and hunting scenes, which of course included turkeys.

To see the rest of Making Medicine's drawings contained in the sketch book (MS 39B) at the National Anthropological Archives click here.

Whitney Hopkins, Reference Intern

National Anthropological Archives

Whitney Hopkins, Reference Intern

National Anthropological Archives

Labels:

American Indian,

Archives,

Artists,

Arts and Design,

Drawings,

History and Culture,

Photographs

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Human Studies Film Archives' Mystery Film Reel Bonus

Missed parts I and II? You can read them here and here.

For those of you who followed HSFA’s posts during October’s Archives Month, we are offering a bonus for November readers. Perhaps the most mysterious clip of all on the mystery film reel—and clearly the most enchanting—is the following. Although we understand nothing of the tradition, if there is one, behind this film footage, there is some resemblance to the acrobatic performances of Japanese firefighters atop tall extension ladders.

And, as an extra added bonus, this film clip resonated with other early 20th century film footage screened as part of the first presentation by University of Maryland professor Oliver Gaycken at Northeast Historic Film’s Summer Film Symposium, “A Modern Cabinet of Curiosity: The George Kleine Educational Film Catalogue.” The wonder is: which is more amazing, the man and the boy or the flies (who are trained and not glued or otherwise affixed to the surface)?

Pamela Wintle

Human Studies Film Archives

For those of you who followed HSFA’s posts during October’s Archives Month, we are offering a bonus for November readers. Perhaps the most mysterious clip of all on the mystery film reel—and clearly the most enchanting—is the following. Although we understand nothing of the tradition, if there is one, behind this film footage, there is some resemblance to the acrobatic performances of Japanese firefighters atop tall extension ladders.

And, as an extra added bonus, this film clip resonated with other early 20th century film footage screened as part of the first presentation by University of Maryland professor Oliver Gaycken at Northeast Historic Film’s Summer Film Symposium, “A Modern Cabinet of Curiosity: The George Kleine Educational Film Catalogue.” The wonder is: which is more amazing, the man and the boy or the flies (who are trained and not glued or otherwise affixed to the surface)?

Pamela Wintle

Human Studies Film Archives

Labels:

Archives,

Asian,

Film and Video,

History and Culture

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

As Always, Adina: A Perspective of a Life through Letters

“If we are successful as archivists, the historical record will speak for this [the nation’s] past, in a full and truthful voice. And, as a society, we will be wiser for understanding who and where we have been.”

--John Fleckner

As an intern in the Archives Center, I have the opportunity to watch archivists hard at work preserving the documentary evidence of the past and the present. Through my program, Smith at the Smithsonian, I am conducting independent research. For my project, I am using a collection of over five hundred letters that Adina Mae Via wrote to her boyfriend, Franklin

Robinson, from 1951 to 1960. They are part of the Robinson-Via Family Papers, 1845-2001.

Adina’s letters are a consistent record of how she presents herself to Franklin during her transitions from high school to the workforce in 1950s rural Maryland. As I delve deeper into her letters, I learn about the details of her everyday life; from how often she washes her hair, to the cost of her long distance phone bill, to how long she spent planting tobacco, to how much she enjoys her newfound independence from her job. Yet, there is just as much to discover from what is left unwritten.

To my surprise, Adina explicitly mentions race only once in her letters writing, “they had four colored people down [at the farm] today” on August 27, 1956. Furthermore, once I learned she attended a segregated high school, I began to wonder how she saw the world in terms of the racial inequalities that existed. I am in the process of researching the demographics of the area where she lived in an effort to learn what Adina’s environment physically looked like, whether on her drive to work, in church, or shopping in downtown D.C. As I scrutinize Adina’s life from my twenty-first century perspective, I realize that I must try to see the world from her viewpoint. In doing so I am better able to learn from her and share the multiple truths and complexities of her life. Through Adina’s letters I am able to reflect on Fleckner’s words by examining “who and where we have been” as an American society. But to truly learn from her, I must recognize our similarities and reflect upon how I too am sometimes immune to the inequalities before me.

Rachel Dean, Smith College Intern

Archives Center, National Museum of American History

--John Fleckner

| Adina Via, 1955 |

| Letter from Adina Via to Frank Robinson, January 15, 1951 |

Robinson, from 1951 to 1960. They are part of the Robinson-Via Family Papers, 1845-2001.

Adina’s letters are a consistent record of how she presents herself to Franklin during her transitions from high school to the workforce in 1950s rural Maryland. As I delve deeper into her letters, I learn about the details of her everyday life; from how often she washes her hair, to the cost of her long distance phone bill, to how long she spent planting tobacco, to how much she enjoys her newfound independence from her job. Yet, there is just as much to discover from what is left unwritten.

| Adina Via, 1955 |

Rachel Dean, Smith College Intern

Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Labels:

Animals,

Archives,

Collection Spotlight,

Correspondence

Wild Goose Chase

|

| "The Spruce Goose" landing on November 2, 1947. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives Record Unit 371, Box 2, Folder: March 1975 |

On November 2, 1947 Howard Hughes, famed businessman, philanthropist, director, and aviator, flew the HK-4 Flying Boat for its first and only flight. “The Spruce Goose” now lives at the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon. But did you know that for a brief moment the plane was a part of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s collections?

Before the “The Spruce Goose” moved around the country in search of a permanent home, the plane had an interesting history of its own. Hughes designed and built the HK-4 during World War II under a contract with the Defense Production Corp. Hughes’ company, Hughes Tool Company, built the plane with a 320-foot wingspan, sixty percent longer than a Boeing 747, and large enough to transport about 700 soldiers into battle. The plane made of birch, poplar spruce, maple and balsa wood, because of wartime restrictions on metal, was given the nickname “The Spruce Goose”, even though birch was the primary material used. However, the plane’s astonishing twenty-three million dollar cost and years of slow progress set the project back. It was completed in 1946 after the war had ended and despite its successful maiden journey, fears about the strength of a wooden plane devalued its worth and the plane was never put into production. Hughes, who called the plane “Hercules”, maintained a crew for his beloved plane’s prototype until his death in 1976.

In 1975, the Summa Corporation (a Hughes Company) owned Hughes’ H-1 Racer, the fastest landplane of its time. The Smithsonian wanted this plane for its exhibits, while the Summa Corporation wanted to purchase “The Spruce Goose.” However, since “The Goose” was built under a government contract and held by the US General Services Administration, it could not be directly sold to the private Summa Corporation. Thus, the plane was transferred to the Smithsonian and shortly thereafter sent to the Summa Cooperation in exchange for the H-1 Racer. The H-1 Racer was placed on display in the National Air and Space Museum’s “Golden Age of Flight” exhibit.

“The Spruce Goose’s” tale does not end there. After Hughes’ death in 1976 the Wrather Cooperation bought the plane and housed it in a hanger in Long Beach, California. In 1988, the Walt Disney Company bought the plane. Finally, in 1992 co-founders of the Evergreen Aviation Museum submitted a proposal to Disney, who were soliciting a permanent home for “The Spruce Goose.” The proposal stated that the new museum would design a state-of-the-art exhibition space around the plane. Disney accepted the proposal and in 1993 Hughes’ plane finally landed for the final time. “The Spruce Goose” underwent a full restoration and in 2001 made its debut in a new exhibit.

Courtney Esposito, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Institutional History Division

Labels:

Collection Spotlight,

Current Events

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)