“A nation stays alive if its culture stays alive.”

-Nancy Dupree, obituary, New York Times, September 12, 2017

Nancy Dupree, founder of the Afghanistan Center of Kabul University (ACKU) passed away September 10, 2017. Shortly before her death, the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Film Center and Norman Miller, Director of the American Universities Field Staff Documentary Film Program, sent 22 hours of digital video files from a 1972 film project to our colleagues in Kabul at the Afghan Center. The project focused on documenting the town of Aq Kupruk, about 320 miles northwest of Kabul in Balkh Province.

|

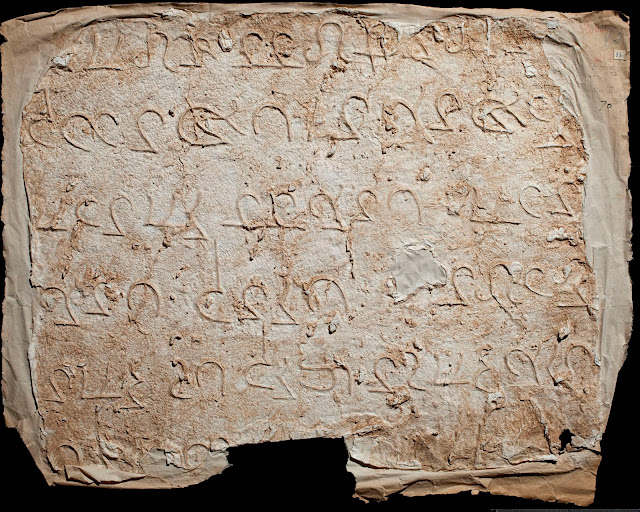

| Aq Kupruk, Smithsonian National Anthropological Film Collection, (sihsfa_2006_05_op_001) |

Five films were edited from the project but few ever anticipated that the full 22 hours would ever be of significant interest. But that was before the conflicts that began with Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan and which continue to this day. Looking back over the past 45 years so much has changed and so much has been lost. This put the documentation of local life in places like Aq Kupruk in a much different perspective. But let’s start at the beginning.

In the early 1970s Norman Miller engaged documentary filmmakers Herbert Di Gioia and David Hancock in a series of innovative film projects based on comparative examination of particular cultures focused on themes related to variables such as social organization, modes of subsistence (e.g., pastoralism, agriculture, etc.), as well as factors influencing social change. The Afghanistan film project was one of these in addition to projects done in Bolivia, Kenya, Taiwan and China. The series—entitled Faces of Change —represented a high point in U.S. funding for anthropological filmmaking based on the educational value and presumed capacity of such films to foster broad understanding of cultural differences around the world.

On May 1, 1975 the series premiered at the Smithsonian Hirshhorn’s auditorium where Smithsonian Secretary, S. Dillon Ripley and anthropologist Margaret Mead provided remarks. Mead, then regarded as anthropology’s leading public intellectual, stressed the urgency of documenting non-Western cultures around the world before they ‘disappeared’ or their traditional lifeways were irretrievably lost. The event marked the formal launch of the Smithsonian National Anthropological Film Center (NAFC). While the promotion that Margaret Mead gave the Center as a place to carry forward documentation and preservation of indigenous and non-Western cultures might today appear somewhat naïve, the Faces of Change series was very much on the cutting edge of an ethnographic genre and in line with the mandate of the Center. What Mead and others also recognized on that occasion was that however important the filming of other cultural worlds might be to us, we—as ethnographers, photographers and filmmakers—could only acquire access to these worlds through the grace of local people like the Afghan villagers in Aq Kapruk. Moreover, the film records that were created through such projects were held not only for our own purposes, but held very much in trust for the peoples who opened their doors and lives to us.

|

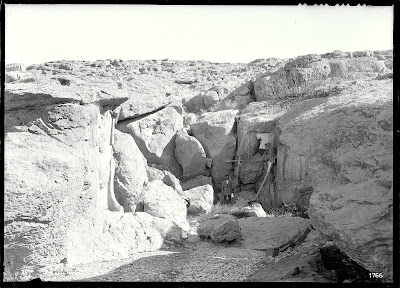

| Smithsonian National Anthropological Film Collection (sihsfa_2014_02_image_001) |

What of the village of Aq Kupruk and those individuals who allowed the filmmakers into their homes and lives? What is known of them? We know that the Afghanistan people have continued to live through decades of wars. Not only have many been killed but their cultural heritage and that of their nation is imperiled. Norman Miller, the producer of the series, told us that the town of Aq Kupruk was badly damaged during the Russian war and Naim and Jabar, the boys in Naim and Jabar, one of the best known films of the five-part Afghan project were killed along with the translator who worked with the filmmakers. Undoubtedly, the lives of many other individuals and families have been lost or tragically altered.

|

| Smithsonian National Anthropological Film Collection (sihsfa_2005_05_op_003) |

Pam Wintle, Senior Film Archivist

National Anthropological Film Collection, National Anthropological Archives

John P. Homiak, Director

National Anthropological Archives

Sources consulted:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/10/world/asia/nancy-hatch-dupree-afghanistan-dead.html

https://lis653.wordpress.com/2017/09/24/nation-building-through-information-sharing-nancy-dupree-and-the-afghanistan-center-at-kabul-university/

https://digitalcollections.barnard.edu/object/yearbook-1949/mortarboard-1949#page/81/mode/2up/search/hatch

John P. Homiak, Director

National Anthropological Archives

Sources consulted:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/10/world/asia/nancy-hatch-dupree-afghanistan-dead.html

https://lis653.wordpress.com/2017/09/24/nation-building-through-information-sharing-nancy-dupree-and-the-afghanistan-center-at-kabul-university/

https://digitalcollections.barnard.edu/object/yearbook-1949/mortarboard-1949#page/81/mode/2up/search/hatch