Showing posts with label Arts and Design. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Arts and Design. Show all posts

Friday, October 25, 2019

The Interplay of Art, Music, and Portraiture

American portraiture captures rich conversations between

artists, musicians, and singers. On the occasion of the Smithsonian’s Year of

Music, this essay explores the interplay of art, music, and portraiture in the

United States, from the Early Republic to today.

During the eighteenth century, artists were often inspired

to portray individuals and groups in the act of playing instruments or singing.

A popular theme was the informal family concert, which exemplified the harmony

and personal values shared by the represented members. An example is the

painting Family of Dr. Joseph Montégut (c. 1797-1800), which has been

attributed to José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza. It depicts a

French surgeon who has settled in New Orleans. He is surrounded by his wife,

great aunt, and children, who are about to play for their parents. Two hold flutes,

while a daughter’s hands are poised on the pianoforte keys. This composition of

a French Creole family in Spanish-governed New Orleans presents a vision of

musical and domestic harmony, which had precedents in European art tradition. https://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-museum/collections/visual-art/artists/jos-francisco-xavier-de-salazar-y-mendoza

From the 1790s through the 1830s, theater and concert

performances proliferated and by the mid-nineteenth century, music had become a

public commodity. A leading European virtuoso, the Swedish singer Jenny Lind, toured

the United States from 1850-1852, in part with the sponsorship of P.T. Barnum. Many

American artists portrayed the popular “Swedish Nightingale,” including Francis

Bicknell Carpenter, whose 1852 oil painting depicts Jenny Lind in costume,

holding a musical score book.

Jenny Lind by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, oil on canvas, 1852. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Eleanor Morein Foster in Honor of First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton (NPG.94.123)

From 1892 to 1895, the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák was director of the National Conservatory of Music in

America. His famous symphony From the

New World (1893) reflected his interest in African American and Native

American music. He promoted the idea that American classical music should

follow its own models instead of imitating European composers. Dvořák

helped inspire our composers to create a distinctly American style of classical

music. By the twentieth century, many American composers, such as Leonard

Bernstein, Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, and Charles Ives incorporated diverse

musical genres into their compositions, including folk, jazz, and blues.

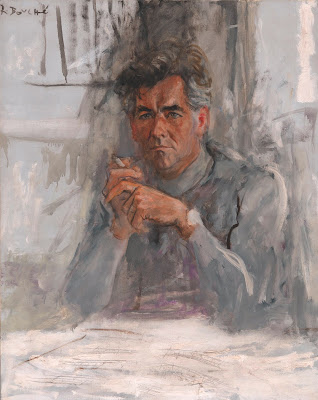

As a composer, pianist, and conductor, Leonard Bernstein made

a profound impact on American music by collaborating with the performing arts. His

interests ranged from classical music and ballet to jazz and musicals. In an

oil portrait of 1960, René Robert Bouché portrayed Bernstein in a moment of

reflection, with the papers of the musical score he is writing scattered across

the desk in front of him.

Leonard Bernstein by René Robert Bouché, oil on canvas, 1960. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Springate Corporation. © Denise Bouche Fitch (NPG.92.3)

The composer George Gershwin and his brother, lyricist Ira

Gershwin, were also highly versatile, having collaborated on popular musicals

and a folk opera. Both brothers also painted interesting self-portraits, which

can be viewed in the Gershwin collection in the Music Division of the Library

of Congress. In a 1934 oil portrait in the collection of the National Portrait

Gallery, George Gershwin represented himself in profile with a musical score

and his hand alighting upon the piano keys.

Self-Portrait by George Gershwin, oil on canvas board, 1934. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Ira Gershwin. © Estate of George Gershwin (NPG.66.48)

The following year, the Gershwin brothers debuted Porgy

and Bess, “an American folk opera,” which broke new ground in musical

terms. Soprano Leontyne Price appeared in the 1952 revival touring production

of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, which brought her first major success. Less

than a decade later, in 1961, Price became the first leading African-American

opera star when she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera. Bradley Phillips

created this formal oil painting of Leontyne Price within a stage setting in

1963. It is one of several portraits he made of the singer. The artist

expressed the admiration he felt for her immense talent when seeing her perform

onstage.

Leontyne Price by Bradley Phillips, oil on canvas, 1963. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Ms. Sayre Sheldon (NPG.91.96)

Artists Thomas Eakins and George P.A. Healy also created portraits

of singers and musicians. In the medium of painting, these artists were able to

convey the intensity and precision of the musicians in their performances. Thomas

Eakins asked his model Weda Cook to repeatedly sing a particular phrase from

Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah, so

he could explore the position and movement of her mouth and vocal chords for

his portrait Concert Singer (1890-1892).

In this manner, he recreated the immediate sense of a formal concert with the contralto

singing on the stage and the conductor’s hand and baton raised in the lower corner.

https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/42499.html

George P.A. Healy visited virtuoso Franz Liszt in Rome and created

this 1868-1869 oil portrait of him playing the piano in an inspired moment. Healy

even convinced the composer to allow Ferdinand Barbedienne to cast his hands in

bronze, an artifact Healy later kept in his studio. https://callisto.ggsrv.com/imgsrv/FastFetch/UBER1/ZI-9HFT-2014-JUN00-SPI-142-1

Both artists not only portrayed the physical characteristics of musicians and

singers but also the inner passion and mental concentration they brought to

their performances. As such, they recreated the emotional spirit of the music

for viewers.

James McNeill Whistler thought about his paintings in terms

of musical titles and themes. He created not only portraits of musicians but also

discussed the subtle tonalities of his more abstract urban scenes and landscapes

in musical terms. In 1878, Whistler defended the titles of his paintings: “Why

should not I call my works ‘symphonies,’ ‘arrangements,’ ‘harmonies,’ and ‘nocturnes’?...As music is

the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter

has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of colour.” This analogy between

music and painting was Whistler’s primary means for defending his paintings

against criticism. Indeed, he published this defense in the journal The World during his libel lawsuit

against critic John Ruskin, who referred to Whistler’s 1875 oil painting of

fireworks in London, Nocturne in Black

and Gold: The Falling Rocket, as “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s

face.” https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/nocturne-black-and-gold-falling-rocket-64931

Whistler’s use of music as a metaphor for painting was intended to build

support for the concept that color, form, and painterly technique were the

primary elements of an artwork. Whistler brought this correlation of painting

and music to public attention with his artworks, which in turn influenced other

artists and musicians.

Regional painter Thomas Hart Benton praised “James McNeill

Whistler[’s art]...tone, colors harmoniously arranged…Whether you can

distinguish one object from another or not, whether the thing painted looks

like a man, woman, or dog, mountain, house or tree, you have harmony and the

grandest artistic aim, it is the truly artistic aim.” Benton was a self-taught

and performing musician who invented a harmonica tablature notation system used

in current music tutorials. He was also a cataloguer, collector, transcriber,

and distributor of popular music. He had musical gatherings for family and

friends at his home in Kansas City. These sessions were commemorated on a 1942 recording

by Decca Records called Saturday Night at

Tom Benton’s, which featured chamber and folk music. Benton’s friend, the

popular actor and singer Burl Ives, shared his passion for American songs.

During the Great Depression, Ives traveled the country gathering and playing

folk songs, and Benton made sketches of folk musicians in different regions. In

a 1950 lithograph titled the Hymn Singer

or the Minstrel, Benton portrayed

Ives playing the guitar.

Burl Ives by Thomas Hart Benton, lithograph on paper, 1950. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY (NPG.85.141)

In 1973, Benton was commissioned to paint his last mural, The Sources of Country Music, for the

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, with support from the

National Endowment for the Arts. He decided the mural “should show the roots of

the music–the sources–before there were records and stars,” and he created a

lively, flowing composition of country folk musicians, singers, and

dancers. https://www.arts.gov/about/40th-anniversary-highlights/thomas-hart-bentons-final-gift

Artist LeRoy Neiman featured Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong,

Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Benny Goodman, and other

famous jazz performers in his group portrait Big Band (2005), which is held at the Smithsonian National Museum

of American History. It took Neiman ten years to complete this mural-size

tribute to eighteen jazz masters, which the LeRoy Neiman Foundation presented to

the Smithsonian after the artist’s death in 2012. Neiman frequented jazz clubs,

where he befriended and sketched these performers. In 2015, the LeRoy Neiman

Foundation donated funds to the Smithsonian towards the expansion of jazz

programing during the annual celebration. See the following two part guide to

this group portrait of jazz greats: https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/neiman-jazz

and https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/neiman-jazz-2

One can discover further portraits and biographies of

notable composers, musicians, and singers in the Catalog of American Portraits

(CAP). In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the CAP, a

national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from

the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the

online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s

website: https://npg.si.edu/portraits/research/search

The Smithsonian is celebrating the Year of Music with a wide

variety of collection highlights and programs. To learn more, please visit: https://music.si.edu/smithsonian-year-music

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Bibliography:

Cheek, Leslie Jr., Director. Souvenir of the Exhibition Entitled Healy’s Sitters. Richmond:

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1950.

Coleman, Patrick, ed. The

Art of Music. San Diego, CA, and New Haven, CT: San Diego Museum of Art in

association with Yale University Press, 2015.

Fargis, Paul, and Sheree Bykofsky, et al. New York Public Library Performing Arts Desk

Reference. New York, NY: Stonesong Press, Inc., Macmillan Company, and New

York Public Library, 1994.

Fortune, Brandon. Eye

to I: Self-Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery. Washington, D.C:

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Munich: Hirmer Verlag,

2019.

Gontar, Cybèle, ed. Salazar: Portraits of

Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785-1802. New Orleans, LA: Ogden Museum

of Southern Art and University of New Orleans Press, 2018.

Henderson, Amy, and Dwight Blocker Bowers. Red, Hot and Blue: A Smithsonian Salute to

the American Musical. Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery and

National Museum of American History, in association with the Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1996.

Kerrigan, Steven J. “Thomas Eakins and the Sound of

Painting.” Paper presented at the James F. Jakobsen Graduate Conference,

University of Iowa, 2012. https://gss.grad.uiowa.edu/system/files/Thomas%20Eakins%20and%20the%20Sound%20of%20Painting.pdf

Mazow, Leo G. Thomas

Hart Benton and the American Sound. University Park, PA: Penn State University

Press, 2012: http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-05083-6.html

.

Ostendorf,

Ann. “Music in the Early American Republic.” The American Historian (February 2019): 1-8.

Phillips, Tom. Music

in Art: Through the Ages. Munich and New York, NY: Prestel-Verlag, 1997.

Struble, John Warthen. History

of American Classical Music: MacDowell through Minimalism. New York, NY: Facts

on File Publishers, 1995.

Walden, Joshua S. Musical

Portraits: The Composition of Identity in Contemporary and Experimental Music.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Wilmerding, John, ed. Thomas

Eakins. Washington, D.C. and London: National Portrait Gallery and Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1993.

Labels:

2019 Archives Month,

Artists,

Arts and Design,

History and Culture,

Museums,

National Portrait Gallery

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

American Women's Role as Collectors, Patrons, and Museum Founders

As collectors, patrons, and museum founders, American women have played an influential role in national and international art circles from the late nineteenth century until today. With the rise of first-wave feminism, women acquired greater financial independence and access to education and professional careers. They also gained confidence in visiting galleries and museums and participating in cultural organizations. In turn, women commissioned and acquired fine art and decorative objects directly from the artists, or through dealers and commercial galleries. Some even went on to found museums in an effort to share their collections with broader audiences.

From the 1890s to the 1920s, these female patrons were quintessential "New Women." The author Henry James popularized the term, which referred to the growing number of feminists who made their presence felt in cultural, educational, and political groups. Active in the suffragist cause, they exhibited their art collections to raise funds for the movement. In honor of the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative, which celebrates the centennial of women's suffrage in the United States, this study of female collectors, patrons, and museum founders highlights the women who made a substantial impact on the cultural advancement of their generations.

One of the Smithsonian Institution’s nineteen museums owes its existence to some of the earliest women founders. In 1897, sisters Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt opened the Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum) in New York. Their grandfather Peter Cooper was the industrialist and inventor who had established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a free school for adults, in 1853. The Hewitt sisters founded their museum as part of Cooper Union and curated its collection of drawings, prints, textiles, furniture, and decorative art objects, which they had acquired in the United States and Europe. They aimed to create a "practical working laboratory," where students and artists could interact with the objects and be inspired by the designs.

A few years later, in 1903, Isabella Stewart Gardner opened her Boston mansion, Fenway Court, to the public. Isabella Stewart was married to the prominent banker and civic leader John Lowell Gardner, who shared her interest in art collecting and traveling. After his death in 1898, she carried out their plans to build a private museum in the style of a Venetian palace with an inner garden courtyard. In her last will, she instructed that Fenway Court (now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) would be for "the education and enjoyment of the public forever."

Ultimately, Isabella Stewart Gardner amassed a collection of nearly 3,000 objects that includes fine and decorative art from America, Europe, and Asia. Its treasures span classical antiquity and the Renaissance to the modern art of her own day. Not only did she collect art, but she also supported the influential art historian Bernard Berenson, who advised her collecting practice. She was also a patron of the artists James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Anders Zorn, who created remarkable portraits of her. Zorn's first commission from Gardner is an 1894 etching that depicts her seated in an Italian "scabello" armchair, which appears to merge in the shadow of an opulent drapery. She is dressed in a stately, long black dress and fur mantle with a plumed headpiece that echoes the coat of arms in the background.

Like Isabella Stewart Gardner, Katherine Sophie Dreier was both a collector and a patron. Together with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Dreier established the Société Anonyme in New York City. She later added the subtitle “Museum of Modern Art: 1920” to commemorate the year it was founded. With Duchamp's assistance, Dreier became the driving force behind this first "experimental museum" of contemporary art in America. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, she organized and funded an extensive schedule of programs, exhibitions, and publications that featured over seventy American and international artists. In 1941, Dreier and Duchamp promised the Société Anonyme’s collection of more than 1,000 modernist works to the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven. Although Dreier was not successful in establishing an independent museum, the Société Anonyme served in part as a model for the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Around the 1930s, women patrons actively launched some of New York's leading museums: the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. In 1929, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller invited her friends Lillie Plummer Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan to join her in founding the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), as a way to support contemporary artists. The three women selected A. Conger Goodyear as president of the board of trustees, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. as the museum’s director. MoMA established a canonical modern art collection, which it augmented with a program of avant-garde exhibitions from America and abroad. As the museum grew, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller continued to play a pivotal role. In addition to donating over 2,000 works and providing acquisition funds, she acted as treasurer and trustee. Furthermore, she collected nineteenth-century folk art, which she gave to Colonial Williamsburg in 1939 and was transferred to the newly-built Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in 1957.

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art turned down sculptor and patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s offer to donate her collection of modern American art, she took matters into her own hands. In 1930, she founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, contributing about 700 works to its core collection. Under its first director Juliana Force, the museum became an influential center for American art. Indeed, the founder had wanted her museum to be "devoted both to assembling the best of American art past and present and to fostering the work of living artists, particularly those working in avant-garde styles." Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's long-term commitment to living artists is exemplified by this 1968 bronze cast after the 1916 original portrait bust, which she commissioned from the struggling young artist Jo Davidson.

A portrait commission led to the founding of another major New York City museum. The artist and collector Baroness Hilla Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, who was from an aristocratic family in Alsace, then part of Germany, had immigrated to the United States in 1927. When she painted the businessman Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1928, the two became friends and collaborators. Rebay convinced Guggenheim to begin collecting abstract art. As his advisor, she connected him to artists in Europe and eventually helped him acquire the more than 700 works that would form the basis of his museum. In 1939, he named Rebay the first director of the new Museum of Non-Objective Painting (today the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum).

Rebay curated the museum's American and European exhibitions, and wrote about and lectured on abstract art. In 1943, Guggenheim and Rebay commissioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright to build the innovative, spiraling museum building that opened in 1959. She established the Hilla von Rebay Foundation in 1967 to "foster, promote, and encourage the interest of the public in non-objective art." Rebay's art collection and archive became part of the Guggenheim Museum after her death that same year. A 2005 retrospective exhibition of Rebay's artwork highlighted her pivotal role in founding the Guggenheim Museum.

Solomon R. Guggenheim's niece Peggy (Marguerite) Guggenheim shared his passion for abstract art, including Cubism and Surrealism. The gallerist, collector, and patron opened the Art of This Century Gallery in New York in 1942. A combined museum and commercial gallery, Art of This Century exhibited European and American artists, and gave Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko their first solo shows. During World War II, Guggenheim went even further in her role as patron, and assisted many artists in their escape from Nazi-controlled areas of Europe to America.

By 1947, Guggenheim decided to close her New York gallery and move back to Europe. She had spent many years on the continent becoming acquainted with the work of avant-garde artists like Man Ray, who photographed her in 1925. This print came from a photo session for an article about influential foreigners residing in Paris in the Swedish weekly Bonniers Vickotidnig. Guggenheim is shown in an elegant cloth-of-gold evening dress by Paul Poiret and a headdress by Vera Stravinsky.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection opened in 1980 under the management of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, to which she had bequeathed her art collection and palazzo, stipulating that the artworks remain in the Venetian residence.

Like Peggy Guggenheim, the collectors and patrons Anne Tracey Morgan and Marjorie Merriweather Post founded museums in stately residences. They also shared a common interest in French history and culture. Anne Tracey Morgan was a philanthropist who supported relief efforts for France during and after World War I and World War II. In 1929, Morgan presented a seventeenth-century palace museum to France, which became the Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt. Its collection focuses on the historical, cultural, and artistic relations of our two nations from the seventeenth century to the present. In 1932, she became the first American woman to be appointed as a commander of the French Legion of Honor.

Marjorie Merriweather Post was a philanthropist who likewise received the French Legion of Honor for funding the construction of field hospitals in France during World War I. Post was an astute businesswoman who expanded her family's Postum Cereal Company to form the General Foods Corporation, which she directed until 1958. She purchased the 1920s Georgian-style Hillwood mansion in Washington, D.C. in 1955, and opened it as a museum in 1977. Post hoped her rare collection of eighteenth-century French and Russian imperial fine and decorative art "would inspire and educate the public." The Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens includes exceptional portraits of European and American historical figures, as well as Post's own portrait commissions of herself and her family members. Alfred Cheney Johnston's photograph of young Marjorie Merriweather Post shows her great poise in a formal gown and feather headdress and veil, which she wore when received by King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace in 1929. Callot Soeurs, a woman-owned fashion design house in Paris, created her presentation at court dress.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C. also owes its existence to a forward-thinking woman collector and patron. In 1981, Wilhelmina Cole Holladay and her husband Wallace F. Holladay incorporated NMWA. After renovating the historic Masonic Temple, they opened the museum in 1987. The couple had begun collecting women's artworks in the 1960s, when scholars and the public were beginning to recognize that women were underrepresented in major museum collections and exhibitions. Today, the collection includes over 4,500 works of fine and decorative art by American and international women artists that span the sixteenth century to the present. NMWA’s exhibitions, programs, and research library aim to advance women in the visual, literary, and performing arts. In 2006, Wilhelmina Cole Holladay received the National Medal of Arts from the United States and the Legion of Honor from France.

Women did not limit their activities to Europe and cities on the East Coast. They also created museums across the United States, in addition to funding and organizing "museums-without-walls" at fairs and international expositions, and contributing to charitable organizations. Portraits played an important role in reinforcing their status as art collectors and founders of museums. One can discover further portraits and biographies of notable women in the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP). In 1966, the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery founded the CAP, a national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum's website: Catalog of American Portraits.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Portraits of Women Patrons:

Portrait of Sarah Cooper Hewitt in French Costume, by J. Carroll Beckwith, 1899, pastel crayon on paper mounted on linen, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt (1938-57-890). https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18351229/

Eleanor Garnier Hewitt, by Antonia de Bañuelos, 1888, oil on canvas, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt (1938-57-737). https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18350779/

Isabella Stewart Gardner, by John Singer Sargent, 1888, oil on canvas, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, 1924 Bequest of Isabella Stewart Gardner (P30wI). https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/10867

Self-Portrait, by Katherine S. Dreier, 1911, oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier (1952.30.6). https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/48054

Portrait of Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (Abby Greene Aldrich), by Robert Brackman, 1941, oil on canvas, Private collection, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

http://www.artfixdaily.com/artwire/release/1414-the-abby-aldrich-rockefeller-folk-art-museum-to-hold-60th-anniver

Self-Portrait at 14, by Hilla Rebay, August 1904, drawing, Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York, NY (M0007). https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/findings/discovering-baroness-searching-hilla-rebays-past

Portrait of Miss Anne Morgan, by Walter Dean Goldbeck, c. 1905-1925, oil on canvas, Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt, FR , Donation of Mrs. Wood, the niece of the sitter (59C 24 or 53C 24).

http://musee.louvre.fr/bases/lafayette/notice.php?lng=1&idOeuvre=490&vignette=oui&nonotice=1&no_page=1&total=1&texte=&titre=anne%20morgan&localisation=&periode=&artiste=goldbeck,%20walter%20dean&date=&domaine=&f=3110&images_sans=sans&nb_par_page=36&tri=Nom&sens=0

Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, by Michele Mattei, color photograph, "You Are Invited: The National Museum of Women in the Arts Celebrates 25 years," National Museum of Women in the Arts and usairwaysmag.com, March 2012, p. 66, ill. https://nmwa.org/sites/default/files/shared/finalusairwayssection_lowres.pdf

Bibliography:

Dreier, Katherine S., Marcel Duchamp, and George H. Hamilton. Collection of the Société Anonyme: Museum of Modern Art 1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1950.

Friedman, B.H., and Flora Miller Irving. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: A Biography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978.

Guggenheim, Peggy. Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict. Foreword by Gore Vidal; Introduction by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. New York: Universe Books, 1979.

Holladay, Wilhelmina Cole. A Museum of Their Own: National Museum of Women in the Arts. With contributions by Philip Kopper. New York: Abbeville Press, 2008.

King, Catherine and Dianne Sachko Macleod. "Women as Patrons and Collectors." Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2018: http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002022267

Masinter, Margery F. Sarah and Eleanor: The Hewitt Sisters, Founders of the Nation's Design Museum. New York: Cooper Hewitt Museum, 2016.

Morgan, Anne. The American Girl: Her Education, Her Responsibility, Her Recreation, Her Future. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1915.

Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House Trade Paperback, 2003.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. American Empress: The Life and Times of Marjorie Merriweather Post. New York: Villard Books, 1995.

Tharp, Louise Hall. Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1965.

Vail, Karole P.B., ed. The Museum of Non-Objective Painting: Hilla Rebay and the Origins of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. With contributions by Bashkoff, Tracey Bashkoff, John G. Hanhardt, and Don Quaintance. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2009.

From the 1890s to the 1920s, these female patrons were quintessential "New Women." The author Henry James popularized the term, which referred to the growing number of feminists who made their presence felt in cultural, educational, and political groups. Active in the suffragist cause, they exhibited their art collections to raise funds for the movement. In honor of the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative, which celebrates the centennial of women's suffrage in the United States, this study of female collectors, patrons, and museum founders highlights the women who made a substantial impact on the cultural advancement of their generations.

One of the Smithsonian Institution’s nineteen museums owes its existence to some of the earliest women founders. In 1897, sisters Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Sarah Cooper Hewitt opened the Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum) in New York. Their grandfather Peter Cooper was the industrialist and inventor who had established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a free school for adults, in 1853. The Hewitt sisters founded their museum as part of Cooper Union and curated its collection of drawings, prints, textiles, furniture, and decorative art objects, which they had acquired in the United States and Europe. They aimed to create a "practical working laboratory," where students and artists could interact with the objects and be inspired by the designs.

A few years later, in 1903, Isabella Stewart Gardner opened her Boston mansion, Fenway Court, to the public. Isabella Stewart was married to the prominent banker and civic leader John Lowell Gardner, who shared her interest in art collecting and traveling. After his death in 1898, she carried out their plans to build a private museum in the style of a Venetian palace with an inner garden courtyard. In her last will, she instructed that Fenway Court (now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) would be for "the education and enjoyment of the public forever."

Ultimately, Isabella Stewart Gardner amassed a collection of nearly 3,000 objects that includes fine and decorative art from America, Europe, and Asia. Its treasures span classical antiquity and the Renaissance to the modern art of her own day. Not only did she collect art, but she also supported the influential art historian Bernard Berenson, who advised her collecting practice. She was also a patron of the artists James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Anders Zorn, who created remarkable portraits of her. Zorn's first commission from Gardner is an 1894 etching that depicts her seated in an Italian "scabello" armchair, which appears to merge in the shadow of an opulent drapery. She is dressed in a stately, long black dress and fur mantle with a plumed headpiece that echoes the coat of arms in the background.

|

| Isabella Stewart Gardner, by Anders Leonard Zorn, 1894, etching on paper, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.91.34) |

Like Isabella Stewart Gardner, Katherine Sophie Dreier was both a collector and a patron. Together with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, Dreier established the Société Anonyme in New York City. She later added the subtitle “Museum of Modern Art: 1920” to commemorate the year it was founded. With Duchamp's assistance, Dreier became the driving force behind this first "experimental museum" of contemporary art in America. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, she organized and funded an extensive schedule of programs, exhibitions, and publications that featured over seventy American and international artists. In 1941, Dreier and Duchamp promised the Société Anonyme’s collection of more than 1,000 modernist works to the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven. Although Dreier was not successful in establishing an independent museum, the Société Anonyme served in part as a model for the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Around the 1930s, women patrons actively launched some of New York's leading museums: the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. In 1929, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller invited her friends Lillie Plummer Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan to join her in founding the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), as a way to support contemporary artists. The three women selected A. Conger Goodyear as president of the board of trustees, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. as the museum’s director. MoMA established a canonical modern art collection, which it augmented with a program of avant-garde exhibitions from America and abroad. As the museum grew, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller continued to play a pivotal role. In addition to donating over 2,000 works and providing acquisition funds, she acted as treasurer and trustee. Furthermore, she collected nineteenth-century folk art, which she gave to Colonial Williamsburg in 1939 and was transferred to the newly-built Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in 1957.

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art turned down sculptor and patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s offer to donate her collection of modern American art, she took matters into her own hands. In 1930, she founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, contributing about 700 works to its core collection. Under its first director Juliana Force, the museum became an influential center for American art. Indeed, the founder had wanted her museum to be "devoted both to assembling the best of American art past and present and to fostering the work of living artists, particularly those working in avant-garde styles." Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's long-term commitment to living artists is exemplified by this 1968 bronze cast after the 1916 original portrait bust, which she commissioned from the struggling young artist Jo Davidson.

|

| Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, by Jo Davidson, 1968 cast after 1916 original, bronze sculpture, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.68.7) |

Rebay curated the museum's American and European exhibitions, and wrote about and lectured on abstract art. In 1943, Guggenheim and Rebay commissioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright to build the innovative, spiraling museum building that opened in 1959. She established the Hilla von Rebay Foundation in 1967 to "foster, promote, and encourage the interest of the public in non-objective art." Rebay's art collection and archive became part of the Guggenheim Museum after her death that same year. A 2005 retrospective exhibition of Rebay's artwork highlighted her pivotal role in founding the Guggenheim Museum.

Solomon R. Guggenheim's niece Peggy (Marguerite) Guggenheim shared his passion for abstract art, including Cubism and Surrealism. The gallerist, collector, and patron opened the Art of This Century Gallery in New York in 1942. A combined museum and commercial gallery, Art of This Century exhibited European and American artists, and gave Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko their first solo shows. During World War II, Guggenheim went even further in her role as patron, and assisted many artists in their escape from Nazi-controlled areas of Europe to America.

By 1947, Guggenheim decided to close her New York gallery and move back to Europe. She had spent many years on the continent becoming acquainted with the work of avant-garde artists like Man Ray, who photographed her in 1925. This print came from a photo session for an article about influential foreigners residing in Paris in the Swedish weekly Bonniers Vickotidnig. Guggenheim is shown in an elegant cloth-of-gold evening dress by Paul Poiret and a headdress by Vera Stravinsky.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection opened in 1980 under the management of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, to which she had bequeathed her art collection and palazzo, stipulating that the artworks remain in the Venetian residence.

Like Peggy Guggenheim, the collectors and patrons Anne Tracey Morgan and Marjorie Merriweather Post founded museums in stately residences. They also shared a common interest in French history and culture. Anne Tracey Morgan was a philanthropist who supported relief efforts for France during and after World War I and World War II. In 1929, Morgan presented a seventeenth-century palace museum to France, which became the Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt. Its collection focuses on the historical, cultural, and artistic relations of our two nations from the seventeenth century to the present. In 1932, she became the first American woman to be appointed as a commander of the French Legion of Honor.

Marjorie Merriweather Post was a philanthropist who likewise received the French Legion of Honor for funding the construction of field hospitals in France during World War I. Post was an astute businesswoman who expanded her family's Postum Cereal Company to form the General Foods Corporation, which she directed until 1958. She purchased the 1920s Georgian-style Hillwood mansion in Washington, D.C. in 1955, and opened it as a museum in 1977. Post hoped her rare collection of eighteenth-century French and Russian imperial fine and decorative art "would inspire and educate the public." The Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens includes exceptional portraits of European and American historical figures, as well as Post's own portrait commissions of herself and her family members. Alfred Cheney Johnston's photograph of young Marjorie Merriweather Post shows her great poise in a formal gown and feather headdress and veil, which she wore when received by King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace in 1929. Callot Soeurs, a woman-owned fashion design house in Paris, created her presentation at court dress.

|

| Marjorie Merriweather Post, by Alfred Cheney Johnston, 1929, gelatin silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Francis A. DiMauro (NPG.20011.92) |

Women did not limit their activities to Europe and cities on the East Coast. They also created museums across the United States, in addition to funding and organizing "museums-without-walls" at fairs and international expositions, and contributing to charitable organizations. Portraits played an important role in reinforcing their status as art collectors and founders of museums. One can discover further portraits and biographies of notable women in the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP). In 1966, the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery founded the CAP, a national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum's website: Catalog of American Portraits.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Portraits of Women Patrons:

Portrait of Sarah Cooper Hewitt in French Costume, by J. Carroll Beckwith, 1899, pastel crayon on paper mounted on linen, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt (1938-57-890). https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18351229/

Eleanor Garnier Hewitt, by Antonia de Bañuelos, 1888, oil on canvas, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Bequest of Erskine Hewitt (1938-57-737). https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18350779/

Isabella Stewart Gardner, by John Singer Sargent, 1888, oil on canvas, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, 1924 Bequest of Isabella Stewart Gardner (P30wI). https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/10867

Self-Portrait, by Katherine S. Dreier, 1911, oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier (1952.30.6). https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/48054

Portrait of Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (Abby Greene Aldrich), by Robert Brackman, 1941, oil on canvas, Private collection, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

http://www.artfixdaily.com/artwire/release/1414-the-abby-aldrich-rockefeller-folk-art-museum-to-hold-60th-anniver

Self-Portrait at 14, by Hilla Rebay, August 1904, drawing, Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York, NY (M0007). https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/findings/discovering-baroness-searching-hilla-rebays-past

Portrait of Miss Anne Morgan, by Walter Dean Goldbeck, c. 1905-1925, oil on canvas, Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt, FR , Donation of Mrs. Wood, the niece of the sitter (59C 24 or 53C 24).

http://musee.louvre.fr/bases/lafayette/notice.php?lng=1&idOeuvre=490&vignette=oui&nonotice=1&no_page=1&total=1&texte=&titre=anne%20morgan&localisation=&periode=&artiste=goldbeck,%20walter%20dean&date=&domaine=&f=3110&images_sans=sans&nb_par_page=36&tri=Nom&sens=0

Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, by Michele Mattei, color photograph, "You Are Invited: The National Museum of Women in the Arts Celebrates 25 years," National Museum of Women in the Arts and usairwaysmag.com, March 2012, p. 66, ill. https://nmwa.org/sites/default/files/shared/finalusairwayssection_lowres.pdf

Bibliography:

Dreier, Katherine S., Marcel Duchamp, and George H. Hamilton. Collection of the Société Anonyme: Museum of Modern Art 1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1950.

Friedman, B.H., and Flora Miller Irving. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: A Biography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978.

Guggenheim, Peggy. Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict. Foreword by Gore Vidal; Introduction by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. New York: Universe Books, 1979.

Holladay, Wilhelmina Cole. A Museum of Their Own: National Museum of Women in the Arts. With contributions by Philip Kopper. New York: Abbeville Press, 2008.

King, Catherine and Dianne Sachko Macleod. "Women as Patrons and Collectors." Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2018: http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002022267

Masinter, Margery F. Sarah and Eleanor: The Hewitt Sisters, Founders of the Nation's Design Museum. New York: Cooper Hewitt Museum, 2016.

Morgan, Anne. The American Girl: Her Education, Her Responsibility, Her Recreation, Her Future. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1915.

Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House Trade Paperback, 2003.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. American Empress: The Life and Times of Marjorie Merriweather Post. New York: Villard Books, 1995.

Tharp, Louise Hall. Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1965.

Vail, Karole P.B., ed. The Museum of Non-Objective Painting: Hilla Rebay and the Origins of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. With contributions by Bashkoff, Tracey Bashkoff, John G. Hanhardt, and Don Quaintance. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2009.

Labels:

Artists,

Arts and Design,

History and Culture,

Museums

Monday, October 30, 2017

The Role of Portraiture in the Alliance of the United States and France

After the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and after the American Continental Congress had chosen the “United States” as the name for the new nation, the Congress adopted a model commercial treaty for France on September 17, 1776. One month later, Benjamin Franklin, one of the seven Founding Fathers, traveled to France with this model treaty, aiming to secure assistance in the war against Britain. After negotiations, in March 1778, King Louis XVI presented Franklin with the trade and defense alliance treaties, which had been signed in Paris on February 6 of that year. Through these treaties, the French extended their support to the Americans in the Revolutionary War. Portraiture celebrated and strengthened the relationship between our two countries.

Franklin’s fame as a philosopher, scientist, and statesman brought attention to the American cause, and he drew admirers among the French court at Versailles and in various intellectual circles. He served as minister to France from 1778 until 1785, and his likeness was captured in formal portraits as well as pieces made for popular culture by French artists. Joseph Siffred Duplessis, court painter to King Louis XVI, depicted Franklin’s strength of character in a series of paintings and pastels, with the earliest version garnering public attention at the 1779 Salon du Louvre exhibition. Leading artist Jean-Antoine Houdon, who created sculpture busts of several Founding Fathers, including Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, portrayed these subjects in neo-classical robes or historical costumes relating to democratic ideals.

In 1784, Houdon was commissioned to create a full-length marble statue of Washington for the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, which led him to accompany Franklin on a trip to America. He visited George Washington at Mount Vernon in October 1785 and cast a life mask of him, which he used for his sculpture bust series, and in turn influenced other artists’ depictions. Although Washington never visited France, his image was celebrated in numerous portraits as president and military leader.

Statesman and philosopher Thomas Jefferson was portrayed in 1786, during his tenure as an American Minister in Paris, in a refined and formal manner by artist Mather Brown. This oil painting went to his friend John Adams and descended in the Adams family. Adams and Jefferson were brought together as trade negotiators in France, and they exchanged portraits as tokens of their friendship. In the portrait’s background, there is an allegorical sculpture of the figure of Liberty, holding a pole with a Phrygian cap at the top. Jefferson admired French culture and supported the country’s political ideals. From 1840 to 1848, King Louis-Philippe commissioned artist George Peter Alexander Healy to create a portrait series of American presidents and statesmen for the historical collection at the Château de Versailles, which included John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Andrew Jackson, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, John Paul Jones, George Washington, and Daniel Webster.

Several important group portraits documented the battles of the Revolutionary War and the following American treaty meetings with France and Britain. Around 1825, John Vanderlyn painted an oil portrait of George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette that places them at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Washington was impressed by the valor of young Lafayette who was wounded at this battle and recommended him for the command of a division in a letter to Congress. Lafayette was a heroic figure, who provided his own support and influenced state officials to send more French aid and forces to fight alongside the American military. King Louis-Philippe commissioned artist Auguste Couder to create the 1836 oil portrait of the Siege of Yorktown for the Château de Versailles (Galerie des Batailles). Generals George Washington, Comte de (Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur) Rochambeau, and Marquis (Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert) de Lafayette and other military officers are depicted with the Siege of Yorktown on October 17, 1781, in the background. This battle was a critical victory when the British General Earl Charles Cornwallis surrendered to Generals Washington and Rochambeau and the combined American and French military forces. Benjamin West portrayed the principal American Peace Commissioners John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin in two unfinished oil studies from 1783 for a larger painting, which was never executed of the Signing of the Treaty of Paris. The Treaty of Paris was signed by representatives of the King George III government of Great Britain and the United States of America on September 3, 1783, in Paris, thereby ending the American Revolutionary War. This treaty and the separate peace treaties between Great Britain and the nations that supported the American cause—France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic—were known collectively as the Peace of Paris.

Historic American portrait collections are at the Musée Carnavalet, Musée du Louvre, Musée National du Château de Versailles, Musée National de la Légion d’Honneur, and the Musée du Château de Blérancourt in France. Musée National de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris has created a special exhibition area to feature the portraits of honored American recipients of the order. On August 8, 1929, Anne Morgan presented a museum to France, which became the Musée National de la Cooperation Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt. This museum’s collection showcases the historical, cultural, and artistic relations of our two nations from the seventeenth century to the present. In America, the Society of the Cincinnati was founded in May 1783, and a French branch of the Society was established in January 1784. The two associations honor the military officers of our two nations who fought in the American War for Independence and seek to maintain the friendship between the United States and France. The Society of the Cincinnati Museum in Washington, DC, has a notable portrait collection of leading American and French officers who participated in the American Revolutionary War.

In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP), a national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s website: http://npg.si.edu/portraits/research.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Websites:

Figure of Louis XVI and Benjamin Franklin, by Charles-Gabriel Sauvage, called Lemire Pere, c. 1780–85, porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (83.2.260)

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/4894?sortBy=Relevance&ft=benjamin+franklin+and+louis+xvi&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

John Adams, by Mather Brown, 1788, oil on canvas, Boston Athenaeum, MA, (B.A.UR.72)

https://www.bostonathenaeum.org/about/publications/selections-acquired-tastes/john-adams-1788

George Peter Alexander Healy portrait collection, Musée National du Château de Versailles, FR

http://musee.louvre.fr/bases/lafayette/3110.php?lng=1&texte=&artiste=%22george+healy+peter+alexander%22&titre=&localisation=&date=&periode=&domaine=&images_sans=sans&submit=Start+the+search&nb_par_page=36&tri=Nom&sens=0

Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine, by John Vanderlyn, c. 1825, oil on canvas, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, (0126.1018)

https://collections.gilcrease.org/object/01261018

Siege of Yorktown, 17 October 1781, by Auguste Couder, 1836, oil on canvas, Musée National du Château de Versailles, FR, (MV 2747)

http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#6863d5d4-9e6b-4058-a3f1-0f3a739459d1

American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain, by Benjamin West, c. 1783–1819, oil on canvas, Winterthur Museum, DE, (1957.0856)

http://museumcollection.winterthur.org/single-record.php?resultsperpage=20&view=catalog&srchtype=advanced&hasImage=&ObjObjectName=&CreOrigin=&Earliest=&Latest=&CreCreatorLocal_tab=&materialsearch=&ObjObjectID=&ObjCategory=Paintings&DesMaterial_tab=&DesTechnique_tab=&AccCreditLineLocal=&CreMarkSignature=&recid=1957.0856&srchfld=&srchtxt=benjamin+west&id=2de3&rownum=1&version=100&src=results-imagelink-only#.WfFQN02Ww5Q

Bibliography:

General Editor Valérie Bajou et al. Versailles and the American Revolution. Versailles: Palace of Versailles and Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo Publisher, 2016.

Ferreiro, Larrie D. Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It. New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

|

| Benjamin Franklin, by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, c. 1785, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.87.43) |

In 1784, Houdon was commissioned to create a full-length marble statue of Washington for the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, which led him to accompany Franklin on a trip to America. He visited George Washington at Mount Vernon in October 1785 and cast a life mask of him, which he used for his sculpture bust series, and in turn influenced other artists’ depictions. Although Washington never visited France, his image was celebrated in numerous portraits as president and military leader.

|

| Thomas Jefferson, by Mather Brown, 1786, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.99.66) |

Several important group portraits documented the battles of the Revolutionary War and the following American treaty meetings with France and Britain. Around 1825, John Vanderlyn painted an oil portrait of George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette that places them at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Washington was impressed by the valor of young Lafayette who was wounded at this battle and recommended him for the command of a division in a letter to Congress. Lafayette was a heroic figure, who provided his own support and influenced state officials to send more French aid and forces to fight alongside the American military. King Louis-Philippe commissioned artist Auguste Couder to create the 1836 oil portrait of the Siege of Yorktown for the Château de Versailles (Galerie des Batailles). Generals George Washington, Comte de (Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur) Rochambeau, and Marquis (Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert) de Lafayette and other military officers are depicted with the Siege of Yorktown on October 17, 1781, in the background. This battle was a critical victory when the British General Earl Charles Cornwallis surrendered to Generals Washington and Rochambeau and the combined American and French military forces. Benjamin West portrayed the principal American Peace Commissioners John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin in two unfinished oil studies from 1783 for a larger painting, which was never executed of the Signing of the Treaty of Paris. The Treaty of Paris was signed by representatives of the King George III government of Great Britain and the United States of America on September 3, 1783, in Paris, thereby ending the American Revolutionary War. This treaty and the separate peace treaties between Great Britain and the nations that supported the American cause—France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic—were known collectively as the Peace of Paris.

|

| George Washington, by Jean-Antoine Houdon, c. 1786, plaster, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG. 78.1) |

In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP), a national portrait archive of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to the present day. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s website: http://npg.si.edu/portraits/research.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Websites:

Figure of Louis XVI and Benjamin Franklin, by Charles-Gabriel Sauvage, called Lemire Pere, c. 1780–85, porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (83.2.260)

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/4894?sortBy=Relevance&ft=benjamin+franklin+and+louis+xvi&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2

John Adams, by Mather Brown, 1788, oil on canvas, Boston Athenaeum, MA, (B.A.UR.72)

https://www.bostonathenaeum.org/about/publications/selections-acquired-tastes/john-adams-1788

George Peter Alexander Healy portrait collection, Musée National du Château de Versailles, FR

http://musee.louvre.fr/bases/lafayette/3110.php?lng=1&texte=&artiste=%22george+healy+peter+alexander%22&titre=&localisation=&date=&periode=&domaine=&images_sans=sans&submit=Start+the+search&nb_par_page=36&tri=Nom&sens=0

Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine, by John Vanderlyn, c. 1825, oil on canvas, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, (0126.1018)

https://collections.gilcrease.org/object/01261018

Siege of Yorktown, 17 October 1781, by Auguste Couder, 1836, oil on canvas, Musée National du Château de Versailles, FR, (MV 2747)

http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#6863d5d4-9e6b-4058-a3f1-0f3a739459d1

American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain, by Benjamin West, c. 1783–1819, oil on canvas, Winterthur Museum, DE, (1957.0856)

http://museumcollection.winterthur.org/single-record.php?resultsperpage=20&view=catalog&srchtype=advanced&hasImage=&ObjObjectName=&CreOrigin=&Earliest=&Latest=&CreCreatorLocal_tab=&materialsearch=&ObjObjectID=&ObjCategory=Paintings&DesMaterial_tab=&DesTechnique_tab=&AccCreditLineLocal=&CreMarkSignature=&recid=1957.0856&srchfld=&srchtxt=benjamin+west&id=2de3&rownum=1&version=100&src=results-imagelink-only#.WfFQN02Ww5Q

Bibliography:

General Editor Valérie Bajou et al. Versailles and the American Revolution. Versailles: Palace of Versailles and Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo Publisher, 2016.

Ferreiro, Larrie D. Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It. New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Monday, October 24, 2016

Portraiture in Transition

|

| Muhammad Ali, Cat’s Cradle (1942–2016) by Henry C. Casselli, Jr. (born 1946), oil on canvas, 1981. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.2002.2) |

At a recent visit to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum in Philadelphia, I was taken by Brian Tolle’s 2012 conceptual mixed-media sculpture of George Washington, No. 1 (First Inaugural Address). The artist created a clear acrylic resin cast of Washington, with a string of glass beads emerging from the president’s mouth and spilling onto the pedestal base, each bead representing one word from his first inaugural address. This portrait is strikingly similar to the French sculptor Jean Antoine Houdon’s original life bust of Washington created at Mount Vernon in 1785. Tolle has begun a “Commander-in Chief” series of mixed-media presidential busts that feature symbolic aspects of each president’s public persona. When I walked into another gallery space at this museum, I found an artist portraying a live model in various poses, part of the Fernando Orellana: His Study of Life exhibition, which honors the centenary of the death of the Academy’s influential art teacher Thomas Cowperthwaite Eakins. Eakins’s teaching program led to a greater emphasis on the study of human anatomy. He included nude models in his classes, a practice new to American art schools in the nineteenth century.

At the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Henry C. Casselli Jr.’s 1981 oil portrait of Muhammad Ali, entitled Cat’s Cradle, is a dramatic depiction of the strength and power of this famous athlete, as visible in his towering physique. Per author Donald Hoppes, the cat’s cradle of string “became the central motif of the Ali portrait,” referring to the ropes of the boxing ring and Ali’s unique boxing style. Ali commanded public attention as a 1960 Olympic gold medalist and three-time winner of the heavyweight crown. He also was a dedicated spokesman for social and humanitarian concerns.

|

| Esperanza Spalding, a Portrait (born 1984) by Bo Gehring (born 1941), time-based media, 2014. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.2014.83) |

In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP), a national portrait archives of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to current times. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program of more than 100,000 records from the museum’s website at http://npg.si.edu/portraits/research.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Bibliography:

Fortune, Brandon Brame, Wendy Wick Reaves, and David C. Ward. Face Value: Portraiture in the Age of Abstraction. Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with D. Giles Limited, 2014.

Gross, Jennifer R., ed., with contributions by Ruth L. Bohan et al. Société Anonyme: Modernism for America. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Yale University Art Gallery, 2006.

Reaves, Wendy Wick, et al., Eye Contact: Modern American Portrait Drawings from the National Portrait Gallery. Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with University of Washington Press, 2002.

Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition 2013. Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2013.

Monday, November 23, 2015

How to Set Your Thanksgiving Table Like an Artist

It has often been said that we eat first with our eyes. In other words, food must be delicious but it must also be beautifully presented. Where better to derive inspiration for your Thanksgiving tablescape than from the tables of artists and designers? Here are some stylishly set tables from the collections of the Archives of American Art.

Husband and wife design team Charles and Ray Eames are perhaps best known for their graceful swooping chairs either in molded plastic or bentwood and leather, still coveted by hipsters and spawning leagues of knockoffs today. Their breakfast table, seen here, features similar clean lines in the simple dishware they selected. Not fancy by any means but immensely appealing nonetheless.

Bolivian-born Antonio Sotomayor is primarily known for his murals, but he also worked as a ceramicist. Perhaps the paella he is enjoying here is served on plates of his own design! I can't help but want to pull up a seat to this table. The warm wood, the classic cup full of breadsticks, and the whimsical fish-shaped place mats all make for a very welcoming atmosphere.

Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings immigrated to New York from London when he was 25 years old, in 1930. Spinning out cosmopolitan furniture and interior designs from his firm on Madison Avenue, he became one of the most well-known decorators in America. This glam dining room set seen above was conceived when he worked as the principal designer for the Widdicomb Furniture Company. Furniture historians may have more to say about the structure of the pieces but for me, this table is all about the gilded pumpkin centerpiece.

Whether you celebrate with a gold pumpkin or not, we at the Smithsonian Collections Blog wish you a very happy, warm and safe Thanksgiving.

Bettina Smith, Digital Projects Librarian

Archives of American Art

Table #1 - Clean and simple

|

| Table setting at the Eames House, ca. 1950 / unidentified photographer. Aline and Eero Saarinen papers, 1906-1977. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. |

Table #2 - Warm and inviting

|

| Antonio Sotomayor dining on paella, 1983 / Grace Sotomayor, photographer. Antonio Sotomayor papers, circa 1920-1988. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. |

Table #3 - Glitz and Glamour

|

| Dining room by Robsjohn-Gibbings, 1950. Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings papers, 1898-1977, bulk 1915-1977. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. |

Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings immigrated to New York from London when he was 25 years old, in 1930. Spinning out cosmopolitan furniture and interior designs from his firm on Madison Avenue, he became one of the most well-known decorators in America. This glam dining room set seen above was conceived when he worked as the principal designer for the Widdicomb Furniture Company. Furniture historians may have more to say about the structure of the pieces but for me, this table is all about the gilded pumpkin centerpiece.

Whether you celebrate with a gold pumpkin or not, we at the Smithsonian Collections Blog wish you a very happy, warm and safe Thanksgiving.

Bettina Smith, Digital Projects Librarian

Archives of American Art

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Progressive Circle of American Women Sculptors in the Nineteenth Century

Blogs across the Smithsonian will give an inside look at the Institution’s archival collections and practices during a month-long blog-a-thon in celebration of October’s American Archives Month. See additional posts from our other participating blogs, as well as related events and resources, on the Smithsonian’s Archives Month website.

A circle of American women sculptors achieved recognition during the nineteenth century in the United States and abroad, receiving commissions for public sculpture and patronage from private parties. Among these artists, (Mary) Edmonia Lewis, Vinnie Ream Hoxie, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, and Sarah Fisher (Clampitt) Ames were particularly notable. Trained in the neoclassical style, these American sculptors were drawn to Rome, where they studied and were inspired by the ancient classical art and international art community. In turn, they established studios, convenient to both Italian craftsmen who could serve as assistants and to marble stone quarries. Women sculptors were welcomed into Rome’s expatriate community, which in the 1850s included nearly forty active American artists, both male and female. The artists often held open houses at their studios, frequented by visitors to the city, including Ulysses S. Grant, Frederick Douglass, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, all of whom Edmonia Lewis portrayed during their stay.

|

| Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830–1908) by Sir William Boxall (1800–1879), oil on canvas, 1857. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.95.6) |

|

| Edmonia Lewis (1844–after 1909) by Henry Rocher (1824–?), albumen silver print, c. 1870. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.94.95) |

Artists who lived abroad also maintained cultural and political ties with the United States, returning for visits and commissions. Some eventually returned to settle in America. Edmonia Lewis was the first recognized professional African American female sculptor. She created sculptures of the leading figures of the abolitionist and suffragist groups and of Civil War heroes, such as John Brown, Maria Weston Chapman, Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, Wendell Phillips, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, Charles Sumner, and Anna Quincy Waterson. Sculptor Sarah Fisher Ames was an antislavery advocate and a nurse, responsible for a temporary hospital established in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., during the Civil War. Through her activities, she met Abraham Lincoln, which likely led to formal sittings with him, where she made sketches and possibly modeled his features. She created at least five busts of the president. In 1868, the Joint Committee on the Library purchased Ames’s marble Lincoln bust for the U.S. Capitol; institutions in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania acquired the remaining busts. Ames later created a sculpted bust of Ulysses S. Grant, which was exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition.

|

| Vinnie Ream Hoxie (1847?–1914) by an unidentified artist, melainotype, c. 1875. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NPG.78.112) |

Vinnie Ream Hoxie also created a series of portraits of President Lincoln. In 1866 the secretary of the interior commissioned her to create a full-length marble statue of the late president, which was installed in the Capitol Rotunda in 1871. She had previously created a bust of Lincoln from a life sitting in Washington. Her selection for the commission was a result of a heated debate in the Congress. Her opponents were critical of her youth and inexperience. Sarah Fisher Ames also made a bust of Lincoln that received favorable comments. Both works are testimonies of these talented artists’ interpretation of Lincoln as a leader and as an important symbol of freedom. Each portrayed Lincoln in a neoclassical style, emphasizing his humanity and solemnity of purpose. They were the first sculptors to create official commemorative images of him for the U.S. Capitol, representing the principles of the newly united nation. Hoxie also created statues of Samuel Jordan Kirkwood and Sequoyah for the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall Collection.

Ames, Lewis, Hoxie, and Hosmer all exhibited their sculptures at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, which brought them further recognition. At times, this circle of women sculptors faced criticism from the public and male artists. They had to maintain a fine balance from what was expected of a Victorian woman in her dedication to family and home and their ambitions to compete in a male profession. However, this group of progressive women broke new ground for the next generation of female artists, including Anna Hyatt Huntington, Malvina Hoffman, Evelyn Longman, and Bessie Potter Vonnoh.

In 1966, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery founded the Catalog of American Portraits (CAP), a national portrait archives of historically significant subjects and artists from the colonial period to current times. The public is welcome to access the online portrait search program from the museum website of over 100,000 records. The CAP program can be reviewed at the following National Portrait Gallery website: http://www.npg.si.edu/research/ceros.html.

Patricia H. Svoboda, Research Coordinator

Websites:

Tolles, Thayer. “American Women Sculptors.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–10. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/scul/hd_scul.htm

Nichols, Kathleen L. “International Women Sculptors: 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and Exposition.” Posted 2002; updated 2015. http://arcadiasystems.org/academia/cassatt4.html

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) by Sarah Fisher Ames (1817–1901) marble, 1868. U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC (21.0013.000). http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Sculpture_21_00013.htm

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) by Vinnie Ream Hoxie (1847?–1914), marble, 1871. U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC. http://www.aoc.gov/capitol-hill/other-statues/abraham-lincoln-statue

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882) by Edmonia Lewis (1844–after 1909), marble, 1871. Harvard University Portrait Collection, Cambridge (S52). http://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/303587

Thomas Hart Benton (1782–1858) by Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830–1908), bronze, 1868. Lafayette Park, Saint Louis. https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/parks/parks/browse-parks/view-park.cfm?parkID=52&parkName=Lafayette%20Park

Bibliography:

Buick, Kirsten Pai. “Mary Edmonia Lewis: The Biography of a Career, 1859–1876.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1999.

Dabakis, Melissa. A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014.

James, Edward T. et al. Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

Weimann, Jeanne Madeline. Introduction by Anita Miller. The Fair Women. Chicago: Academy Chicago, 1981.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide and Near East Relief

Blogs across the Smithsonian will give an inside look at the Institution’s archival collections and practices during a month long blog-a-thon in celebration of October’s American Archives Month. See additional posts from our other participating blogs, as well as related events and resources, on the Smithsonian’s Archives Month website.

|

| Transit advertisement published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, 28 x 53.5 cm. From the Princeton Poster Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History |

Sadly, milestone historical events per se are often catastrophic. For example, 2015 is the tenth anniversary of the devastating storm Katrina. It is also the hundredth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide by the Ottoman Turks during World War I, and April 24 was observed by Armenians around the world as Genocide Remembrance Day. Although this program and the policies which produced it remain controversial in Turkey, most historians believe that mass killings of Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians were deliberate and planned. When I visited Turkey two years ago, a well-known academic denier of the genocide narrative gave me a signed copy of his book, in which he argues that the Armenians were simply subjected to a forced march because they were thought to be collaborating with Turkey’s enemies, and that such a forced deportation during wartime unavoidably involves hardships.

| Poster published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, 1917. From the Princeton Poster Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History |

One can commemorate this crisis and all its misery, but one can also celebrate the groundswell of humanitarian aid which occurred as a result of it. On April 3 this year a special Friday colloquium was added to the schedule of the NMAH Tuesday Colloquium, which I coordinate for the Museum. The speaker was Shant Mardirossian, the Chairman of the Near East Foundation. His message was to celebrate the philanthropic and humanitarian aid which the Genocide inspired, rather than to concentrate on the horrors of the Genocide itself. Shant related how the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief was established in 1915 just after the deportations began; it was a charitable organization intended to relieve the suffering of the peoples of the Near East and was supported by Henry Morgenthau, Sr., American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Between 1915 and 1930, ACRNE distributed humanitarian relief to locations across a wide geographical range, eventually helping around 2,000,000 refugees. Also known as “Near East Relief,” this program was supported by President Woodrow Wilson. It was an important landmark in the history of American humanitarian aid and philanthropy. As the Museum is currently studying American philanthropic history to inspire new collecting and programming initiatives, this story is especially timely.

| Poster published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, ca. 1915, 47.5 x 31 cm. From the Princeton Poster Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History |

| Card published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, ca. 1917, 7.5 x 11 cm. From the Princeton Poster Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History |

David Haberstich

Curator of Photography, NMAH Archives Center

Labels:

2015 Archives Month,

Archives,

Arts and Design,

Europe

Tuesday, June 2, 2015

Always with the Banjo: Rapid Capture Digitization at the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

|

| How we roll: live banjo music during the RCPP open house. Photograph by Ben Sullivan. |