By David Haberstich

In recent years the Smithsonian Collections Blog has featured numerous posts about women photographers represented in Smithsonian collections. For instance, I’ve blogged about the photographers Katherine Joseph, Dawn Rogala, and Melody Golding, whose work is in the NMAH Archives Center, but now I want to highlight a much earlier Smithsonian effort to celebrate women in photography. The National Museum of American History (then the Museum of History and Technology) featured female photographic artists in a series entitled “Women, Cameras, and Images” in 1969-1970, initiated by Curator of Photography Eugene Ostroff. Although three of these photographers were famous, even legendary, and already included in general histories of photography, two were comparatively unknown at the time. Prints by all five are in the museum’s Photographic History Collection, acquired in conjunction with their exhibitions. This program was an early attempt to emphasize the contributions of women to twentieth-century photography via a series that combined three famous photographers, who utilized standard photographic techniques to achieve their unique personal vision, with two younger, relatively unknown artists who experimented with “obsolete” photographic processes, combined with hand techniques, to interrogate assumptions about the nature of photography. Indeed, Betty Hahn later challenged standard notions about photography (and the nature of her multi-media variations) in the very title of her book, Photography…Or Maybe Not. *

|

| Betty Hahn (b. 1940), "Seasonal Rainbow Transition," gum bichromate with paint on paper, 1968. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History. |

All four exhibitions were accompanied by poster-checklists and formal, if modest, openings. The first show in the series, “Women, Cameras, and Images I,” was a retrospective of Imogen Cunningham’s classic imagery. I well remember her sly humor and witty sarcasm at her opening: she was delightful, and it was especially gratifying for me after my failed attempt to meet her during a trip to San Francisco.

|

| Imogen Cunningham (1882-1976), "Unmade Bed," gelatin silver photographic print, 1957, printed 1957, Smithsonian American Art Museum. |

Above: Gayle Smalley (left) and Betty Hahn (center) talking with Eugene Ostroff at the opening of their exhibition, 1969. Smithsonian photographer unidentified.

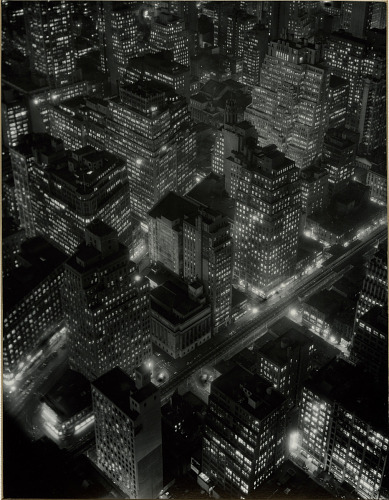

“Women, Cameras, and Images III” was devoted to the work of Berenice Abbott, whose long and influential career ranged from documentation of New York City to the development of techniques for scientific photography, in which she was an important pioneer. Unfortunately, we lacked funds to bring her to Washington for the opening, and I think she never quite forgave me.

|

| Berenice Abbott (1898-1991), "Night Aerial View, Midtown Manhattan," 1933, gelatin silver print. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History. |

Barbara Morgan was the artist of “Women, Cameras, and Images IV.” Noted for her photographs of Martha Graham’s dancers, a major component of the exhibition, she worried about the design of the show, and explained her concern with rhythm and flow in the placement and sequencing of the framed images. I was tempted to let her develop the layout or collaborate with me, but was warned not to permit her participation lest it delay the opening. It was a nail-biter for me as I hung the show, fearing that she didn’t fully trust my curatorial eye, but I needn’t have worried: she was pleased and pronounced it a huge success, telling me “You got it!” She had been honored previously in a similar retrospective solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by my photo-history mentor, Peter Bunnell, and pronounced my design “better.” At social occasions for several years afterward she proudly introduced me as “the man who hung my Smithsonian show, you know,” and we had a lovely and rewarding friendship.

|

| Barbara Morgan (1900-1992), "Martha Graham--Letter to the World--(Swirl)," 1940, gelatin silver print, printed ca.1980. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Virginia Zabriskie. |

However, the series, which originally was intended to continue for another year, foundered and ended when some photographers objected to being “classified” or identified as “women photographers” within a special series, as if each photographer's work couldn't stand on its own merits. Similarly, I recall hearing certain women criticize the creation of Washington’s National Museum of Women in the Arts for what nowadays some might call bad “optics,” appearing to relegate female artists to a separate category rather than striving to integrate them in greater numbers into existing art museum awareness and practice.

Opinions, perspectives, and tactics intended to promote social change often themselves change with the times and the politics of culture, however. In 1970 we found that for some women photographers, the prospect of inclusion in a series of gendered exhibitions (curated by men) entitled “Women, Cameras, and Images” could be interpreted as more demeaning than celebratory, perhaps suggesting mere tokenism. Controversial “optics!” By contrast, the emphasis on equity in the 2020s has regularly employed group solidarity and separation as a logical, effective tactic to highlight marginalized groups and their members’ individual stories--for example, through Black History Month and Women’s History Month. I recently noticed a current exhibition at Lehigh University entitled “Hear Me Roar: Women Photographers II,” reflecting the similar strategy of the Smithsonian’s “Women, Cameras, and Images” exhibitions of the tumultuous late 1960s. I couldn't help smiling.

David Haberstich, Curator of Photography

Archives Center, National Museum of American History

* Reference: Steve Yates, Betty Hahn: Photography or Maybe Not. Essays by David Haberstich and Dana Asbury, catalogue by Michelle M. Penhall. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

No comments:

Post a Comment