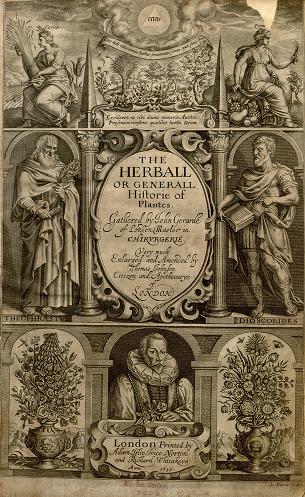

| Garment Workers on the Home Front. Photograph by Katherine Joseph, ca. 1942. © Richard Hertzberg and Suzanne Hertzberg. Katherine Joseph Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History |

Photography was a vibrant and exciting part of her life. Though she ended her career for marriage and motherhood, her work demonstrates an assertive and enterprising personality. She was a determined professional in a field that few women entered. She stood near such luminaries as President Franklin Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frank Sinatra, but also spent considerable time in factories where members of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) worked. She practiced her craft with simple equipment, yet produced results that convey strength, dignity, and respect. Until a few years ago nobody knew anything about her achievements, particularly those closest to her, her children.

Who was she? This was forgotten photojournalist Katherine Joseph. You haven’t heard of her career as an intrepid, enterprising female photographer during the 1930s and 1940s, based mainly in New York City--certainly not after World War II, when she was already married to electrical engineer Arthur Hertzberg and had put her venerable Rolleiflex camera into a closet and taken on the role of spouse and mother. From that point on she never picked up a camera again and did not discuss her premarital photographic adventures with anyone.

| Katherine Joseph near her darkroom. © Richard Hertzberg and Suzanne Hertzberg. Katherine Joseph Papers, 1938-1944, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. |

Recognizing the value of this archive, Richard and Suzanne Hertzberg donated it to the National Museum of American History in 2007. Richard found an intriguing family connection with his own passion for photography. It had remained a mystery, since there was no explicit communication about photography between mother and son--although in the mid–1960s Ms. Joseph handed over to Richard an old Rolleiflex square-format camera, with no background about its history. When he visited the Smithsonian in 2014 to see the complete Katherine Joseph collection, he found many 2 ¼" by 2 ¼" negatives that were clearly taken with the same Rolleiflex his mother had passed on to him, and which he had used to take his first photographs.

Richard also became convinced that a fitting tribute to his mother’s photography would be an exhibition, and he submitted a proposal to the Oregon Jewish Museum / Center for Holocaust Education (OJM / CHE) in Portland, Oregon (he lives in one of the city’s suburbs). OJM / CHE’s Executive Director, Judy Margles, along with the institution’s staff and Exhibition Committee, were enthusiastically supportive. Judy accompanied Richard on his second visit to view the Joseph collection in 2015 and, upon seeing firsthand the material, was even more committed to an exhibit. The two met with National Museum of American History staff, Rosemary Phillips, Cathy Keen, and David Haberstich, to discuss cooperating in making the exhibit, Every Minute Counts - Photographs by Katherine Joseph, happen. Kay Peterson was very helpful from the outset, and Joe Hursey created high–quality TIFF digital images that were used to make new prints for the exhibit. It opened on June 29 and runs to September 25.

Katherine Joseph was born in Odessa, Ukraine in the early 20th century, the youngest of five children. The family immigrated to the United States when she was a baby, and her early years were spent in El Paso and Chicago. Katherine had an independent character; free from “Old World” cultural constraints, she moved to New York City to practice photography. She secured a position with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) that enabled her to document the garment industry labor force before and during World War II. The relationship between worker, machine, and urban/industrial environment was a prominent theme in many of her Union photographs.

The ILGWU was a strong advocate of improving working conditions and promoting employment for all Americans regardless of gender or ethnicity. As such it attracted political attention. Ms. Joseph’s photographic portfolio includes candid views of President Franklin Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Harry Truman, a very young Frank Sinatra, and the colorful New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. One memorable photo of President Roosevelt showed him surrounded by members of the cast from the Union production of “Pins and Needles” when the show was staged for the President at the White House on March 3, 1938.

| Girls sewing, Mexico, 1941. Photograph by Katherine Joseph. © Richard Hertzberg and Suzanne Hertzberg. Katherine Joseph Papers, 1938-1944, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. |

Katherine Joseph’s photographic career also took her far from the garment factories of New York City. In January 1941 she and two friends from Chicago embarked on an expedition to Mexico in an “Americar” manufactured by the Willys–Overland Motor Company. The firm wanted to demonstrate the rugged nature of the car as part of a public relations and advertising campaign. Ms. Joseph was to provide visual proof of the car’s durability through her photographs as it was driven over Mexican roads, paved and unpaved. Her photographs also displayed the dignity of poor farmers, the vibrancy of street markets, and the country’s varied geography.

Whether she was in a Manhattan garment workshop or a Mexican town, Katherine Joseph’s photographs display a profound respect for the fundamental dignity of the people she brought into focus, regardless of their circumstances or position in life. At the same time she was very aware of those circumstances and they became part of the subject matter, serving literally as a compositional frame or stage for the individual lives she presented in her photographs.

In reviewing the Katherine Joseph exhibit at the OJM / CHE--the first public display of her work-- Bob Hicks of Oregon Arts Watch wrote the following:

"Her photography in the 1930s and 1940s slides her neatly into a category of humanistic documentarists that also includes the likes of Dorothea Lange…and Margaret Bourke-White…The images range from the factory floor to the White House…and capture the lives of hourly workers and giants of the entertainment and political worlds. The images in the exhibit are all shot in black and white, lending the work a sense of historical veracity, and are compellingly framed, with the vital trait that excellent news and documentary photographers share of freezing telling moments in intimate and lively circumstances…"For more information about Katherine Joseph and her exhibit at the Oregon Jewish Museum, visit their website: http://www.ojmche.org/.

Richard Hertzberg and David Haberstich

Archives Center, National Museum of American History